Sabrina Imbler: ‘Wonder Is the Animating Force Behind a Lot of My Stories’

“I want to help people think about all the different ways there are to live and to try to keep living.”

Previously in my author conversation series: Morgan Talty, Christopher Soto, R. Eric Thomas, Jasmine Guillory, Alejandro Varela, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Megha Majumdar, Ada Limón, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Crystal Hana Kim and R. O. Kwon, Lydia Kiesling, and Bryan Washington.

*

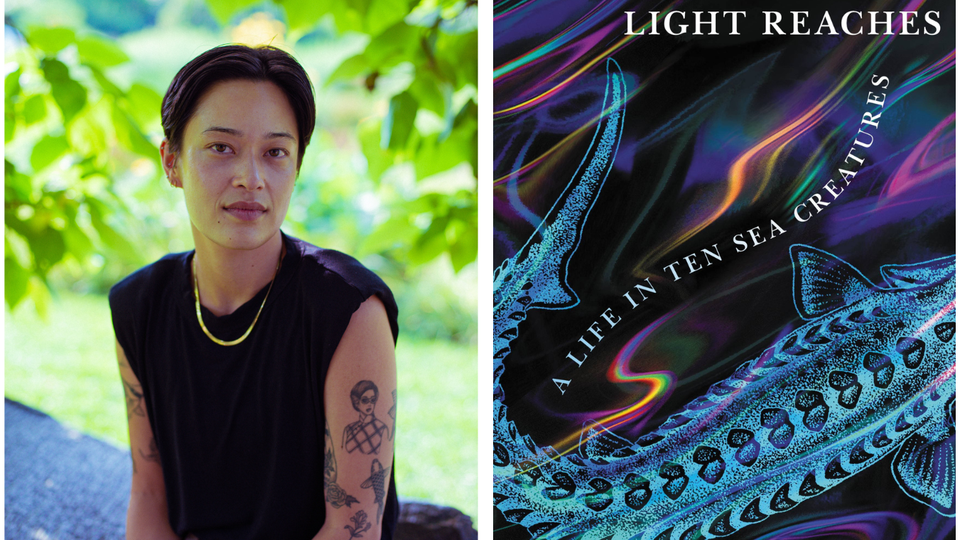

In their debut essay collection, How Far the Light Reaches, journalist Sabrina Imbler profiles 10 creatures that make their home in the depths of the sea, opening a window for readers who will likely never have the chance to encounter these beings in any other way. Braided into these essays are illuminating stories from Imbler’s own family, their community, and their past and present life, a blend of lush nature writing and revelatory storytelling that Imbler makes seem far easier than it is. Expansive and intimate, written with the wonder that drives so much of their work, it is one of my favorite books I’ve read this year.

Imbler is a staff writer at Defector, where they cover creatures; before that, they worked as a reporting fellow on the science and health desk of The New York Times. I’ve loved their writing since I read the first installment of their Catapult column, “My Life in Sea Creatures,” edited by my then-colleague Megha Majumdar. It was a particular treat, then, to get to hear more about their experience writing How Far the Light Reaches, how they approach research and reporting, what they learned about creative work and their own needs while working on this book, and the importance of understanding animals on their own terms.

Nicole Chung: This is a stunning book, Sabrina. I know that some of the ideas began to take shape when you were working with Megha Majumdar on a series for Catapult. Why did you want to write that column?

Sabrina Imbler: I came up with the idea for the column while I was working at Wirecutter, reviewing toasters and sleep masks—it was a great first job, but I think I was missing some of the creative opportunities I’d had in college. A couple of years before that, I’d had a part-time job writing clickbait for an ocean nonprofit, writing 500-word aggregate news posts, where I learned a lot about the ocean and everything that lived in it. I came across a story about an octopus from the species Graneledone boreopacifica—which I had to learn how to pronounce for my audiobook—who brooded her eggs for 4.5 years in a canyon in the deep sea. I was obsessed with the story of this octopus, but I couldn’t write about her in a way that felt meaningful in my capacity at that job. The story stuck with me; I wasn’t quite sure why.

Then I read Angela Chen’s “Data” column at Catapult. I had never considered that you could dovetail science writing and personal writing as well as she did. So I pitched a column to Catapult, the octopus essay and two other pitches I came up with, even though I’d never written anything in this format, braiding the narrative of a creature with my own. Megha found my submission and took a chance on it. It was so helpful to have that column space to try things out—it allowed me to be more hybrid in my form, more experimental in my structure.

Chung: What was it about sea life that helped you access and share these stories about your own experiences, your family, your identity, in new ways?

Imbler: I grew up in California, near tide pools, near the beach. I loved snorkeling on family vacations. I would go to the Monterey Bay Aquarium—that was my favorite place in the world. Being so close to this mysterious force that is the Pacific Ocean and seeing tendrils of it in the seaweed that would wash up, the organisms and animals that would beach, gave me peeks into an element I found so fascinating. I have always been drawn to the sea.

Writing was a place for me to think through my ideas and reach moments of self-discovery, whether it was through fiction or nonfiction. The one thing that has been helpful to me in all aspects of my writing life, both literary and journalistic, is following my obsessions, because it’s hard for me to write something I’m not interested in. I knew I wanted to write about the sea, and my personal story was one way I found that was interesting and generative and allowed me to do that. I didn’t want to write a popular-science book—I didn’t feel I had anything particularly interesting to say in my musings about a dolphin or something—but when I was strongly drawn to the story of this octopus and it got me thinking about my own life, I realized that maybe my life was my channel into writing about my obsession.

Chung: I know you because of Catapult, but of course many people are familiar with your writing because of your journalism, including your great work for the Times and Defector. What is it you especially love about this beat?

Imbler: I always want readers to be able to meet someone through my story, whether a scientist or a creature or a field of thought that’s changing. When I’m writing about other life-forms, I try to be clear and descriptive: This is where they live, this is how long they live, this is how big they are, this is what they eat, this is how they mate. I want to help people think about all the different ways there are to live and to try to keep living.

A challenge is that sometimes the stories I want to pursue aren’t considered “high impact” in the way editors often want—I’m not writing about, you know, an organism that could hold the cure for cancer, or this famous, charismatic creature that might go extinct soon. But wonder is the animating force behind a lot of my stories, and I think it is a powerful lens that can compel people to care about creatures and plants and organisms, even if they don’t seem to have immediate relevance to our lives, even if we could never meet them face-to-face or use our knowledge of them to cure a terrible disease. It’s still important to know and value these creatures and recognize their right to keep surviving. We all have a right to survive on Earth.

Chung: For what it’s worth, one of the more valuable things your work has done for me personally is to help me think more about the fact that we do share this planet with animals we’ll probably never come into contact with, and it’s worthwhile to learn how they experience the world.

There are many creatures in this book, but you’re the life-form at the center. How did you approach writing about your own experiences as a longer project?

Imbler: The editor I chose to work with said in our first meeting that she found it interesting that I was using the lenses we normally apply to understand humans to understand nonhuman animals [and asked]: What about the reverse? How can we understand ourselves in ways we might use to try to understand an animal population? That became a driving force in the way I approached writing about personal aspects of my life in this book. It was really generative to look at my life and think, What things have I done that are related to the fact that I am an organism—behaving on instinct, being motivated by survival, trying to find community?

It was definitely a learning process. I wound up cutting a lot of personal details because I realized both the danger of having so much about yourself out in the world, but also I wanted to protect myself: I am someone to care for, not just the story. I don’t exist in service to the essay. I’m curious how you’ve handled this, as someone who writes memoir?

Chung: I tend to draft like no one will ever read it and then do a lot of revision. You’ll meet people who say that you can’t think about what anyone else will think or say about your memoir, including your family and friends. I get that different writers have different feelings about this. I certainly never want to censor myself. But I always think about what I am personally okay with having out there and what people in my life will think or say, and I’ve had to accept that that’s the kind of writer I am.

Imbler: There are people whose stories I didn’t want to tell. I never believe that the work is more important than the welfare of those I know.

You mentioned censoring yourself. My greatest fear was being canceled on Twitter, so I was like, I have to have the best politics; I have to learn everything there is to know and anticipate every tweet someone could direct at me saying I had erased a population, and finally my editor said, “You’re not actually saying anything, and you’re constantly apologizing.” All I can do is read as much as I can and be honest and move forward with care. But I was definitely censoring myself at first.

Chung: I totally understand this as well—one of my greatest fears is writing something that really hurts someone, or hurts a community, because I made a thoughtless mistake. At the same time, I think trying to learn as much as we can and working with care is about the best any of us can do. The fact that you did this comes through clearly in your book. And it doesn’t read like you censored yourself.

You wrote this book while working as a journalist. How do you balance those two parts of your career? Does your routine vary depending on whether you’re working on a reported piece versus this book and the longer essays in it?

Imbler: I thought I could write [this book] while also having a full-time writing job, which was incorrect. I managed to get book leave, but then I was laid off. When I wrote papers in college, I was like, I have to be in my favorite big chair in the library next to the painting of the bell peppers near the window, or else I can’t be in the zone. But so much of this book was written under just the worst possible circumstances. I wrote a lot of it in my room in the early pandemic when all my roommates were also working from home and the building across the street was being demolished. I had to let go of the idea of having a perfect working space, or mental peace, and be creative in my writing methods.

When I work on reported pieces, it’s very straightforward. I can spend so much time reporting, talking to people, reading papers. At the same time, with a lot of the pieces I do, especially the shorter ones, I know I will never be able to tell the whole story—I’m only skimming the surface or focusing on one corner of it—and so it’s easier to know when to stop researching. With the book, it was harder to figure out when to keep going or stop, or what would be the most useful thing to put in an essay. In the end, what was most helpful was free-writing, just forcing myself to put words on the page, knowing it might be bad. Then I did a lot of rewriting.

As a journalist, I think a lot about notions of objectivity and when you can be in the story, when your personal experiences can be reflected. I tend to disagree with a lot of the more traditional ideas of what constitutes bias in your reporting. Now I’m in a place that allows me to bring my whole self to the story, and I really appreciate that, because for a long time, I felt like I had to be this weird, invisible, objective being in these stories, and I couldn’t be fully present as a person unless I was explicitly writing personal essays.

Chung: I think one of the hallmarks of good personal writing is doing it in a way that allows readers to experience things with you, feel for you, while finding connections to their own lives. If we’re lucky, sometimes we find new empathy for ourselves, too. Did that happen while you were working on this book? Or did you learn anything about yourself through writing it?

Imbler: That’s such a great question, and such a nice way of framing it—finding empathy for yourself. I definitely did. A lot of the essays are about my adolescence, or specific moments in my past, and I think I’d always associated the experiences with a great deal of shame—either shame that society brought on me, or shame that I instilled in myself. But in the bird’s-eye view that you get when you’re looking at the character of yourself, I did develop a lot of empathy for my younger self and the decisions they made.

When I was first writing, I defaulted to self-deprecation; I thought that would be relatable to the reader. But thinking about myself through the lens of an animal made me think about how I was trying to survive, or find community. Sometimes the ways I did that were wrong or corny, but writing about it helped me reach a better understanding of why I did what I did. I have a lot of tenderness for my past self that came about through writing the book, even though writing is not therapy.

Chung: I love that. I also wrote a book during the pandemic, while grieving, and for a while I was stuck in this cycle of self-blame. I didn’t think I was hitting that note especially hard in my writing, but when I shared some early chapters with a friend, she said, “You know, I think you’re being too hard on yourself, which makes me sad for you, and it’s not really serving the story.” It was very helpful for me to hear that.

Were there particular ways that you found to take care of yourself while working on this long and quite demanding project?

Imbler: I’m really glad you had that friend! I think I learned a lot of the techniques that I have now after I wrote those hard sections of the book. The hardest one to write was the essay about my experiences with sexual assault. I would sit down and force myself into my memory, and that was probably a harmful way to access those experiences.

In the winter of 2021, while attending a virtual Tin House workshop, I watched a talk by Terese Marie Mailhot, who mentioned that she puts guardrails in when writing about trauma—she made the point that you need to have a route out so you know how to remove yourself from reliving these memories, and have some sort of care for yourself afterward, and know that there’s never a “right” level that you need to excavate. When I write about personal experiences now, I try to keep that in mind.

Chung: I’m glad you got to hear that, and that it has been helpful to remember. When it comes to treating ourselves like human beings, I think a lot of writers learn the hard way, from our first books. I know I did.

Do you have any tips for hopeful science storytellers?

Imbler: It can be a real treat to experiment. I was so grateful to find space to try things out, even if they didn’t work. And if you want to try to blend science and personal writing, I think it’s especially helpful to ask: What is your full self, and how does that inflect the way you understand the science, or interpret the creature, or engage with the discovery? Try to understand your biases, your experiences, your connections to the subject. I think that can make the work so much richer.