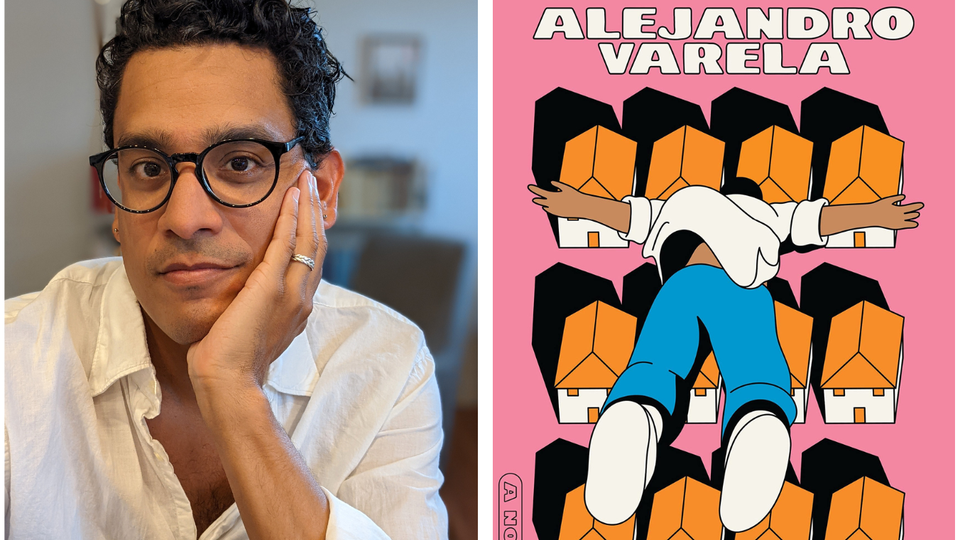

Alejandro Varela on the Reality of Being an Anxious Writer

“All illness, including mental illness, is exacerbated by a lack of community, by feeling alone.”

Previously in my craft conversation series: Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Megha Majumdar, Ada Limón, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Crystal Hana Kim and R. O. Kwon, Lydia Kiesling, and Bryan Washington.

*

When Alejandro Varela, author of The Town of Babylon—one of my favorite debut novels of 2022—reached out to ask if we might chat about writing and anxiety for my newsletter, I knew it was a conversation I wanted to have.

It is my suspicion that nearly every author struggles, to some degree, with the demands of self-promotion. You spend years focused on writing alone, and then suddenly your book is out in the world, an object for public consumption and comment, and you have to learn how to discuss it in front of an audience. You’ve dreamed of publication, the chance to share your work with readers; of course you’re determined to do whatever you can to give your book a fighting chance. But so much is expected of authors these days in terms of visibility and promotion, and being in the public eye does not come easily to all.

From public speaking to social media, burnout to bad reviews, how do writers with anxiety deal with the reality of a public-facing career? How might an author’s anxiety be further complicated or exacerbated if they are also, as Varela put it, constantly “thinking about how to accommodate others, partly because of how colonialism can live in us”? How can authors dealing with anxiety be better supported by their literary communities? I’m grateful to Varela for suggesting this conversation—one that I hope will help some of our fellow anxious writers feel less alone.

Nicole Chung: Alejandro, thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me. Can you start by talking about how your publication experience has been so far?

Alejandro Varela: I’ve found events stressful, because I’m not a very comfortable public speaker or traveler—before the tour, I hadn’t been on a flight in seven years. I think a bit of performance anxiety at an event is actually helpful, but when it crosses into debilitating anxiety, it’s a problem. And so I would take half a Xanax to cut that down. Although I’m pro–anything that works, I still have a bit of a stigma around medication for myself—I feel bad that I can’t get through it on my own, and it hasn’t gotten as easy as I wanted it to, even though it’s gotten easier.

I had a setback when I had my first hometown event at Greenlight Bookstore, after several weeks of travel. It was on my mind all day, but I let the anxiety get ahead of me. I had that kind of subcutaneous buzz of anxiety, and so I took my medicine, and then I couldn’t even get dressed. It was a full panic attack. My husband came in and said, “Take a deep breath, it’s going to be okay”—and I could hear everything he was saying, but the way anxiety works for me is that if it gets too far, then the disassociation begins. I know it’s going to pass, I’ve done all the research, I understand it’s just brain chemicals, and I know no one is coming just to watch me fail, but it was such a shitty feeling. I was disappointed in myself—like, how could I have been on tour for five weeks and still feel this way?

Chung: You had all that accumulated stress from the road too. You’re five, six weeks more tired.

Varela: Yeah, definitely. I biked over to the bookstore and went to the back room and said to the bookseller Jean, an angel: “Have you ever had a writer panic and just cancel?” and they said, “No, but that’s not going to happen, you’re going to be okay—we all love the book, and everyone in that room is here to support you, whatever happens.” My conversation partner was Rumaan Alam, a friend, which took some of the pressure off. And then I got through it, and it went really well, and I was glad for that.

Always, as with every event, I thought, I’m going to take this positive energy with me. And then the next event comes along, and my stomach tightens up again. It’s not been easy. But I do think I’ve made some inroads. I’ve found therapy very helpful … I can fly now. I think I have a sense now of what I can and can’t do.

Chung: I am an anxious person too, which I don’t think I was fully aware of until my parents got very sick. When did you first become aware of your anxiety?

Varela: On 9/11, I was working at a skyscraper two blocks away from the towers. It was a temp job. I got to the building after the first plane had hit. It was a massive building; the company only had one or two floors, and so I went upstairs to the office. Then the second plane hit, and everyone was given the option to go home. I still had no idea what was coming. I thought, I need to get paid, I don’t know if I’ll get paid for the day if I leave. There were a lot of people who’d stayed. We were all watching the window that faced the towers, and the first tower fell, and the whole building shook in a way that was so horrifying—the cloud of smoke coming at us was like something from a movie. Everyone was running away from the window, and I’ll never forget this: An older white guy came out of his office and grabbed my shoulder and said, “You need to relax. Calm down.”

The worst part is, I was relatively calm, because all my life, I’d been focusing on being seen and not heard. Lots of people were running around screaming—I was just moving quickly back to my desk to get my things, yet I was the one he chose to say that to. And in retrospect, you know, fuck him, but at the time I took it to heart. I thought, Oh my god, relax, you’re making a fool of yourself.

I grabbed my things, took all the water bottles I could find, and then everyone started running down the stairs. Some people were calm; some people were crying. One person was catatonic and could not move, so people were lifting her by the elbows, carrying her one step at a time. We got to the 10th floor, and a fire captain told us that below that floor, there was so much debris and smoke that there was no visibility, so we should stay where we were and wait. I sat under a desk reading. I read the same paragraph of a book I’d brought with me, Crime and Punishment, for somewhere between two and three hours. To this day, I have no idea what paragraph it was. People were screaming updates around me. I thought, Maybe we aren’t going to get out of this. And we just waited it out until we were told that it was clear enough to leave. I soaked my undershirt in water, wrapped it around my face, and started the long walk back home. I walked as quickly as I could, but Nicole, I would not run—because in my mind, if I ran, then I wasn’t being calm, and I needed to stay calm.

I don’t know when the nightmares started, but after that, it was a long time before I could fly again. I had no fear about the plane being used as a missile; I just couldn’t be trapped anywhere. And that feeling of being trapped is in my mind now too—I can feel trapped by my expectations, other people’s expectations. Whenever I feel like I can’t get out of a moment, the anxiety begins. My book tour was a little bit of shock therapy. I think I have anxiety genetically and from my own experiences growing up, but 9/11 was the activation, like your parents’ illnesses were for you.

Chung: Yes, like it could have manifested later or differently if not for this deeply traumatic experience that you had. I really appreciate you sharing so much, and I am also sorry if it was painful or upsetting to have to revisit it.

Going into your tour, did you have many conversations with your publisher about your anxiety, your expectations, their expectations? So many times, I’ve heard how important it is for authors to go out and do whatever it takes to promote our books, and of course, many of us are more than willing and want to do our best—but I think sometimes there’s this idea that we’ll all be equally able to put ourselves out there publicly. What did you think your tour would be like?

Varela: I was very naive. My fear of public speaking has been around a long time. I wanted to be an actor when I was a kid. I took a drama class in college, which I had to drop because I couldn’t get over the fear. I’ve turned down jobs, I’ve not done things so I don’t have to speak publicly. When I became a writer, at first I thought, I won’t have to speak; this will be great. I’ll be like Salinger. He just wrote—no one knew where he was. Every year, I’ll just send my editor a new manuscript.

After I sold the book, I knew that I had to go on tour, and I also wanted to, in a way. What the book explores with respect to public health, collective liberation—these things are very important to me, these are conversations I want to have. I knew the only way I’d get to have them is if I went out there. What I call this kind of immigrant gumption kicked in. I thought of my parents, who work fiercely—nothing can keep them down—and I thought, This is the least I can do. This is work, this is your job. So I didn’t tell anyone about my anxiety at first.

At my first event, I felt so anxious, and eventually I had to tell the audience what was happening, because I couldn’t get out of the panic. Once I said it aloud, I was able to read and have a long conversation, and everyone was great and supportive. All illness, including mental illness, is exacerbated by a lack of community, by feeling alone. I think if we could in some way collapse the hierarchy in our society so that our differences weren’t barriers, and we didn’t feel so alone, it would help.

After I tweeted about that experience, my publisher reached out and said, “Don’t worry, we can cancel anything you want to cancel,” but I said, “No, I’m doing this. I’m committed.” I can’t just not show up. I think there’s some internalized capitalism there, right? The most important thing is the job, and not my well-being.

Chung: Yes, and we’re thinking, Are we coming across as “professional,” and what is the standard for “professionalism,” and how might that be different for us?

Varela: Yeah, and you walk into a lot of spaces with majority-white crowds, and there’s that feeling like, oh, I’m the brown kid—I still feel like a kid; I’m 42—and I’m walking into this very white space, and maybe I’ll be judged or pitied. That’s not necessarily true, but that’s the assumption from a lifetime of having those encounters and those feelings. When I speak, I am undoing decades of avoidance, of observing and not participating, and suddenly, I am the center of attention—something I have been raised and conditioned by society to never be. I’d like to get better at it, and I think I have, but it’s a process. I almost feel like equity for a writer from a marginalized community should include a bit more care in these environments—maybe asking, “Hey, what do you need? What would make you feel more comfortable? A meet-and-greet beforehand, a break somewhere between the talk and signing?”

Chung: I don’t mind speaking, and I really love events, but I’ve had some wild questions—and I remember when I finally asked if some of the bookstores and other venues could have people submit questions on note cards, so the moderator or conversation partner could filter out the uncomfortable or kind-of-racist ones. And they were like “Of course, people do this all the time; it’s no big deal.” I had been afraid to ask, because I didn’t want to be seen as difficult or ungrateful, but truly, nobody cared.

Varela: That’s inspiring to me because, sometimes, I forget to set some boundaries and ask for things I need. I think, again, this comes from a lifetime of accommodating, thinking about how to accommodate others, partly because of how colonialism can live in us. I’m always thinking that everything is on my shoulders.

Chung: There obviously aren’t easy fixes, but I’m wondering what else may have helped you.

Varela: Being able to create community—being able to ask folks, “How did you handle this?”—is really important. I feel now that this is my responsibility as someone who has had this experience, and as a queer person of color, I have to be there for anyone who knocks on my door. I don’t know if that’s the reason you opened the door when I knocked, but I have felt that from so many writers of color—from Deesha Philyaw to Robert Jones, Jr., Alexander Chee to Justin Torres. I felt like I was punching above my weight, I had no business asking for their help, but they all showed up for me and talked with me and opened doors. It’s a reminder that we have to be there for each other; we have to support each other. I will be there for whoever asks, and I will do my best.

Chung: There have been so many people in my corner too. It’s helpful to remember that people do want to help; they want you to succeed.

Are there other aspects of being a public-facing author that you’ve found especially challenging or rewarding?

Varela: At the beginning, I was wondering if we even needed to do this, if it was really necessary to put ourselves out there at all—I wondered, Why do we have to show our faces so much? I see why now—the connections I’ve had with audiences, the community I’ve found.

But social media! Social media can be so painful for me. I labor over tweets and Instagram posts as if they were short stories. I have realized that there are good things about social media, but initially, I was afraid of it. I wanted people to take me seriously; I wanted them to focus on my words, not my face, and I saw social media as a slippery slope—where would it go?

Chung: I was not anxious about social media at first, but that was before I had dealt with, oh, so many things online.

Given that tension between the private and public, and what is asked of writers these days, do you think there are ways people can be more supportive?

Varela: It can be as simple as asking. Offering some sort of acknowledgment that, yes, writers have to do this work, but it’s not easy for everyone. Working backwards a bit, thinking about the reception I got at Greenlight and a couple other places, just being able to voice my anxiety to a bookseller or conversation partner and not have them blanch was important. I don’t want to walk into every room and say, “Hey, I have anxiety and PTSD!” But it’s helpful when it feels safe to do that and when someone tells me it’s going to be okay. And then it’s also nice to have someone I can decompress with afterward, who will ask how the event went—someone who can give me notes, let me know what worked, reassure me.

Chung: Is there anything we haven’t touched on about writing and anxiety that you want to talk about?

Varela: Oh, can we talk about reviews? I like reviews; I read reviews; I learn from reviews. I believe in conversations. I have found that the writers of color who’ve read and reviewed my work read and engage with it in a way that’s so meaningful to me. But I’ve noticed that anything negative I’ve heard has been from white writers. It’s like they went in with a preconceived notion, and they didn’t understand the experience of being a marginalized person—it comes with a lens, with pressures, that they didn’t expect. They would say there was too much politics.

Chung: Or there’s not enough conflict or pain for them—like our work exists only to beg for empathy.

Varela: It’s so funny to hear mostly white men say that I’m telling people what to think—and it also goes back to the question of, okay, who’s my audience? They want us in our lanes, I think. They want the trauma porn, they don’t want someone who’s going to read this country or criticize where they may have come from, and that’s all I write about: I am a class-jumping person of color and an observer, and my job is to write what I’ve seen.

Chung: Yes. I really appreciated this conversation—thank you again for suggesting it and being so open.

Varela: Thank you. I think it helps to have these conversations with each other, and if it helps another writer, that’s great. And you know, despite everything we’ve just talked about, if you said to me, “Meet me at your favorite bookstore,” I’m going to get on a plane and go. It is work, and it’s work that I feel I need to do.

*

Thank you for reading! Newsletter sign-ups make my day. If you enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it with a friend or two.

Do you have a question about writing or creative work that you’d like me to answer? You can send it to ihavenotes@theatlantic.com. And let me know if there’s anything you’d especially like to see covered here—I would love to hear from you.