Talking About Care and Craft With Bryan Washington

“I’m less interested in the volume of work than in doing work I really find value in. Which is very different than operating under the clock of capitalism.”

Welcome to I Have Notes, a newsletter featuring essays, advice, notes on writing, and more. This is a free edition, but Atlantic subscribers get access to all posts. Past editions you might enjoy include You Do Not Always Have to Say Yes, How to Organize Your Writing Ideas, A Comforting Apocalyptic Story to Ring in the New Year, and A Choice in Name Only. To support my work and gain access to my full newsletter archive, subscribe to The Atlantic here. And you can always send any thoughts or questions to ihavenotes@theatlantic.com.

*

When I launched this newsletter, I knew that I wanted to hold space for conversations about how we can pursue writing, publishing, and other creative goals without losing compassion for ourselves. In the years when any writing I wanted to do was relegated, by necessity, to the margins of my life, I often felt that I could do my best work only by sacrificing other needful things—whether that meant sleep or meals, healing or recharging time. But the strain and grief of the last few years has forced a kind of recalibration, and I’ve been slowly learning that I can’t do the work I want to do if I approach it as though I’m a machine. The importance of treating yourself humanely has found its way into every class I teach, every writing talk I give; I think of it as an essential aspect of creative work, as important as any craft discussion.

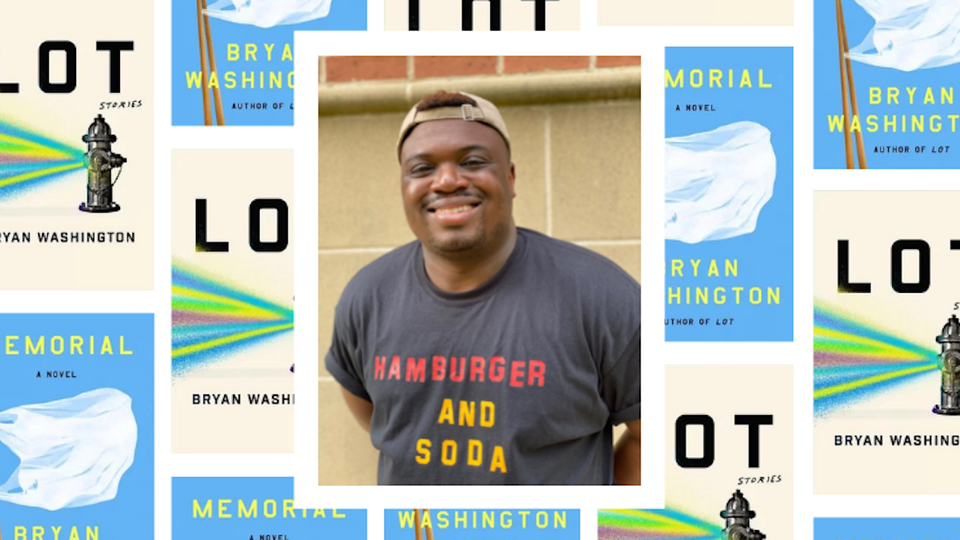

I know I’m not alone in this—when I talk with friends and fellow writers, we frequently find ourselves considering questions of care alongside those of craft, and so I thought it might be helpful (and fun!) to share some of those conversations with you here. Up first is my friend Bryan Washington, award-winning author of Memorial and Lot: Stories, who I got to know while editing several of his essays for Catapult magazine. He’s now writing his second novel, working on the television adaptation of Memorial, and teaching creative writing at Rice University (and you’ll soon be able to read his columns in The New York Times Magazine as well). He’s one of my favorite authors, and while he’s as busy as any writer I know, he is also someone whose generosity is a model for me and for many. I’m grateful that he took the time to chat with me over Zoom about the questions that animate his writing, his approach to teaching, the ways in which he tries to advocate for himself and the needs of his work, and how his community informs his creative process and priorities.

Nicole Chung: Hi, Bryan; thanks so much for talking with me! I know you’ve been working on your next book, and I’m very excited to hear whatever you can share about it.

Bryan Washington: I’ve gotten to the point now where it is what it’s going to be, which is a nice point to arrive at. Once I stopped trying to force a particular kind of story or force particular themes or ideas, it came together and the characters did what they wanted to do in lieu of what I wanted them to do. Which is a bit more woo-woo than I would typically be about storytelling and structure, but at any rate, it’s fortunate that it started coming together last summer.

It’s been fun to work on, which is the best thing I can say about anything I’m working on. It’s enjoyable for me. It’s not building a house, it’s not farm work, it’s not that sort of intensive labor—but it is work, and it does take a toll, particularly if you’re a marginalized author writing about difficult thematic ideas. It can wear on you, and your resources. But once I have an understanding of what I’m trying to do at the scene level, like I do now, I can tell that I’m enjoying it, and that’s when I think a reader might be into it, too.

Chung: In a recent craft essay by Ingrid Rojas Contreras, you’re quoted saying that for you, there are big questions you’re thinking about with every project, and that you usually don’t feel super pressed to supply answers. At what point did you realize this is how you tell stories?

Washington: It happened pretty early on. I realized I’m just not that good at giving answers. For me, supplying answers is also not what will get me to finish a project. Questions like What does it mean to be okay as a person? What does it mean to build a quote-unquote nontraditional relationship within a more traditional environment? What happens if you come of age with a set of beliefs within a particular context, and then you find yourself outside that context and have to reassess what’s important to you? are always fascinating to me, partly because any answer I could proffer would be fraudulent; it’s going to change from person to person.

Chung: How did you get your start writing and publishing?

Washington: I started, I guess, mostly with nonfiction and essays. Getting to work with you at Catapult was important.

Chung: Thank you so much, but you had plenty of great bylines before I got to work with you!

Washington: That was around when I started taking my work more seriously—the craft and the intent of it. Seeing the precision with which you worked with me on my pieces was a shift for me, as was working with Silvia Killingsworth at The Awl and Rachel Sanders at BuzzFeed. Getting to work with y’all specifically was important to me because of the emphasis on thoughtfulness and the journey of a piece. You were also generous with your time—particularly for marginalized and queer writers, it’s rare to find people who encourage you to take the time to not only understand but really bring out the best version of a piece, in lieu of a piece that is meant to explain or justify something or be definitive.

I was fortunate and had more opportunities to fall into things I enjoyed, sometimes just by reaching out and asking, “Can I write for y’all?” I was also thinking through stories set in and around Houston, and stories about queer relationships, but it wasn’t in any strategic way—I thought it was fun. I started submitting to a few fiction contests, and I wouldn’t win, but the judges—particularly Amelia Gray—were really gracious with my submissions, and that was helpful and important to me. I started to think, Okay, I don’t know if there’s a market for the narratives I’m interested in writing, but maybe they could be of interest, and interesting, even if only to folks that I think of myself as being in community with.

Chung: I think so much of being an editor—and perhaps you’ll agree, a teacher?—is learning how to ask questions. How is teaching going for you now? I would think it’s a bit of a balancing act, teaching while writing, especially during a pandemic.

Washington: It’s gone well so far, which I attribute solely to the students I’ve gotten to work with. Most of them are students of color. Some are approaching creative writing from the standpoint of professionalization, but most aren’t. They approach the readings from a point of curiosity, asking, “How does this story work?” So we can spend two weeks reading Raven Leilani and Rachel Khong and Octavia Butler and Weike Wang and trying to figure out how they accomplish what they do. I’m grateful that we’ve gotten to learn from one another. The pandemic has exacerbated a lot of fault lines and fractures in the whole university setup, so I also just admire the fact that my students have been able to navigate that—I tell them all the time, if I’d gone to university during a pandemic, I absolutely would have dropped out.

From a work-balance standpoint, I’ve found that compartmentalizing what I’m doing and when is essential. There are certain days out of the week that are my Rice days, and every other day to some extent is a novel day, and then on other days I’m working on film and television projects. Something that used to be difficult for me is letting the people I’m working with know how my energy is being distributed—saying, like, “Hey, these two days a week, I’m all yours, but after that you might not get a lot out of me until we come back next week.” It was a tricky shift for me to make as a generally anxious person—and then there’s writing from a marginalized background, like if I ask for these things I need, maybe they won’t ask me to work with them again—but I’ve found that folks have been very receptive. It’s partly being very conscientious and also deeply fortunate in who I’ve had the opportunity to work with.

Chung: I’m always interested in thinking about how we can treat ourselves and each other more gently while doing the work we want and need to do. What have you found most helpful in learning how to do this?

Washington: It’s a work in progress, especially during the pandemic; the variables change literally every week. I had to learn how to get better at leaning on my agents and my teams and asking for help or extensions when I need them. Something that’s been really helpful is asking myself a series of questions whenever I get a work ask. It depends on whether it’s coming from an organization or institution, or whether it’s coming from a friend. If it’s an institution or organization, I think: Are these folks that I think of myself as being in community with, or folks who are doing something that I aspire to, that is equitable, that is working toward something positive in my view? If not, I’m probably not going to do it. If it’s an institution, Are they going to pay me my rate? If the answer’s no, then no hard feelings, but I’m not going to do it. If the answer’s yes, then I ask myself if I have time to do this without sacrificing other things that are important to me, like home life or prior obligations. If whatever I’m being asked to do impedes on that, I can’t do it, or I have to push it.

At this point, I’m less interested in the volume of work than in doing work I really find value in, or helping or assisting friends and working with them on something we all find value in. Which is very different than operating under the clock of capitalism, where you have to have, you know, three different pieces in three weeks, and if you don’t make these five lists at the end of the year then the year was a dud—I think that kind of thinking is in many ways incentivized by U.S. publishing and the allegedly well-meaning white folks on most of our mastheads, but I don’t think there’s a lot of value in it.

It’s also helped talking with friends and folks I admire, and hearing what their processes are. I’ve learned by way of osmosis, interviews, podcasts—listening to Jenna Wortham and Mary H. K. Choi and Mira Jacob talk about what it means to work through a narrative moment that brushes against trauma. How does one navigate that? How does one treat oneself? With Lot, I know I didn’t give myself as much grace working through difficult moments. Even with Memorial, I could tell I needed to make changes. For this next novel, I’m trying to give myself the space I need. Maybe there’s a page-and-a-half scene that would normally only take 30–45 minutes to edit, but because of the material, I give myself a few days or a week. Or if I feel it’s not the day, I’ll let myself work on another passage that matches the energy I do have. It feels significantly healthier for me.

Chung: I admire this a lot, and feel like I’m also in the process of learning what to do if writing something feels like it will be too much for me on a given day. Sometimes, after a tough chapter, I’ll give myself time before diving back in. I really believe we do the things we need to do in order to write, and sometimes that is not writing.

You mentioned your film and TV projects—how has it been to work on your creation in a completely different medium?

Washington: It’s been really lovely so far. The grace and the support the A24 team has given me, the attentiveness and thoughtfulness they’ve given Memorial as a project—I really couldn’t ask for more. Again, in lieu of speed, we’ve been trying to work seriously and thoughtfully. I’m deeply conscious of wanting to do right by the co-producers, wanting to do right by all the actors. Of course, in pandemic land, everything has been delayed, so we can actually take a beat and ask: “How can we make this better? How can we make sure it has value for everyone working on it, so they feel good about being part of it?” I want to do my part to cultivate an environment for this project that is as positive and equitable and precise as possible.

Chung: Before we wrap, I wanted to say congrats on joining The New York Times Magazine’s “Eat” column! I love your food writing, and I’m excited to read you there.

Washington: Thank you! I think my first piece drops in March? I’m really excited to think about not only the individual dishes and flavor profiles, but also how context plays such an important role in how a dish comes together—how it’s internalized for us, our friends, our families. Writing in a city like Houston, where we have a multitude of cultures and communities and cuisines that are always combining their contexts, thinking through that is always so interesting. The food component is important to me, but the people are just as important.

Chung: That leads right into my final question, which is about community—a term that gets thrown around a lot, and can be defined in different ways. How do you think about community in a creative context? And are there ways in which your community helps you to write and set your creative goals and do all the other things you want to do?

Washington: I love this question. It’s so interesting; when I think about community, I know what I mean, but it’s tough to articulate. Whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, I’m always trying to write a narrative that I myself would like to read or see, one I’m perhaps not seeing to the extent I would like. When I think of community, I think of my queer friends, my friends of color, and they are who I prioritize in my writing. That’s been so helpful for me to think about throughout the generative process. Something that is deeply important to me is simplicity or clarity of language while working with multiple ideas and dexterous structures, which is partly because accessibility is extremely important to me, and partly because that’s the sort of prose I find myself most often drawn to.

When I think about my community and writing, sometimes it’s a matter of asking, Is this something I would have to explain to someone I’m in community with? If the answer is yes, then maybe an explanatory note is warranted, but if it’s not, then it’s not. If I’m writing nonfiction, I ask myself, Is there a way I can add to this conversation on my own terms that speaks to the folks I would like to speak to in a way I’m not seeing yet? Often it doesn’t feel like there’s anything I can contribute that hasn’t already been said by someone I admire, but occasionally there’s a perspective or shift I think I can offer, in the language I would use in speaking with folks that I’m in community with.

This really drives what I write, how I write it, who I write for—and also who I work with. Your mag might be “general audience,” but are you open to understanding that this is the audience I’m primarily writing to? I’ve found that sometimes I have to be very up-front about who and what I’m trying to prioritize to avoid complications further down the line. But I’ve also found that when I am vocal about this as a requirement for me, many folks are more receptive, and if they’re not, we don’t work together—there’s no ill will, it just means we’re probably not a great fit. When a venue or a person comes along who does understand, I find there is already trust, and when I receive an editorial note, I know it’s coming from a place of thoughtful application.

I know it’s a privilege to be able to be direct about the terms under which I’d like to write. As a marginalized writer, sometimes you might feel that if you ask for too many things or make too many changes, you might not get the opportunity again. But there have been so many moments when I just had to be direct about saying, No, this is not the way. It’s not an attack, it’s that we’re working together on a project and we want it to be the best version possible, so how can we get there?

Chung: Right! And I think you can also view honesty in relationships—personal or professional—as a sign of esteem. You want a genuine collaboration; you want to be aligned on or at least transparent about your priorities. You want to speak about these things with candor and care. So if I think someone is capable of getting that—and hopefully they feel the same about me!—that is a good reflection on our working relationship, not the reverse.

Washington: Exactly. Having the conversation is so important. I’ve learned (from you!) that you can be thoughtful and come from a place of care while simultaneously being precise and transparent about what the work needs. I think I’m pretty mellow (nearly to a fault) about virtually every area in my life but the needs of the work: because one thing I’ve learned is that—as queer folks, as folks of color—if we don’t speak up for the needs of our craft in a media ecosystem saturated by whiteness, absolutely no one else will. They just won’t. If anything, they’ll smile and say that you signed off on the bad thing. And it was difficult to get to a place where I felt comfortable speaking up. But the more you advocate for yourself, the easier it becomes, even if only gradually by way of more reps—because what you expect from yourself and others catches up with the work you’re trying to do. Accountability surfaces on all fronts. And I’m much more comfortable with it now.

*

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider sharing it with a friend or two.

I’m bringing back my advice column starting next week, so send me questions if you’ve got ’em! Or you can always just say hi / recommend a book / let me know if there’s anything you’d especially like to see covered in this newsletter. As always, thank you for spending time with it.