‘Break All the Rules You Can’: A Conversation With Poet Christopher Soto

“I believe that literature can create material change and open new worlds that haven’t existed before.”

Previously in my author conversation series: R. Eric Thomas, Jasmine Guillory, Alejandro Varela, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Megha Majumdar, Ada Limón, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Crystal Hana Kim and R. O. Kwon, Lydia Kiesling, and Bryan Washington.

*

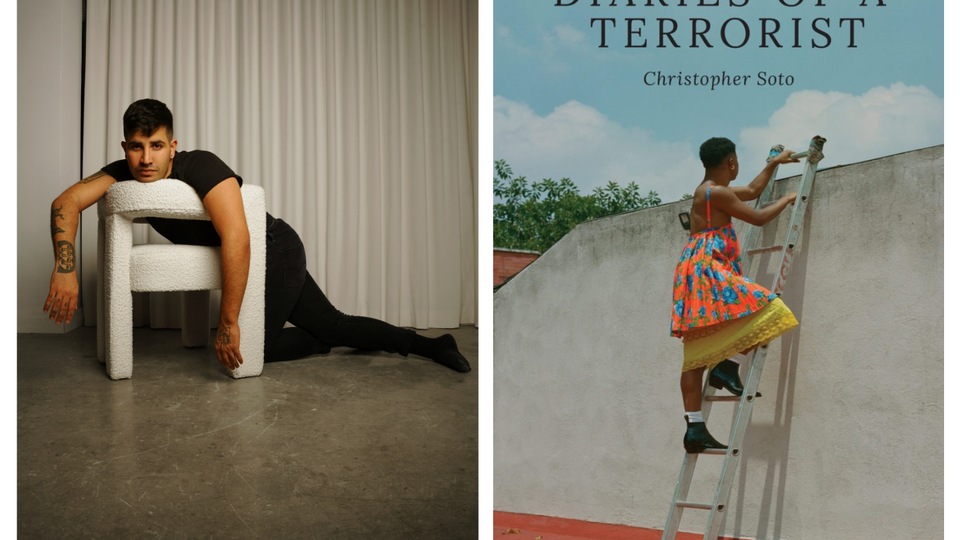

Christopher Soto’s belief that literature can spur change and “open new worlds” permeates his debut poetry collection, Diaries of a Terrorist. In the book, Soto—a recipient of Them’s 2022 Now Award in Literature and co-founder of the Undocupoets Campaign and Writers for Migrant Justice—explores the individual and societal impacts of carceral systems and state-perpetrated violence. The collection is both a challenge and an invitation, allowing readers to confront interconnected legacies of violence and open their imaginations to a more just and equitable future.

In August, Soto traveled to El Salvador, his family’s country of origin, to launch Diaries of a Terrorist there. During our interview last month, he spoke about abuses in El Salvador, the decline of democracy in the United States, how the term literary community can be used and misused, and his approach to writing about abolition from a transnational perspective. He ended by noting how vital it is for poets and writers to read beyond their own experiences, borders, and literary traditions. “Read internationally,” he said, “so that you know craft is nebulous and the rules are meant to be broken.”

Nicole Chung: Diaries of a Terrorist is a resounding condemnation of police violence, incarceration, and the caging of migrants, and a call for collective liberation. What does it mean for you to think and talk about these ideas as an artist—to write poetry both within and about abolitionist movements?

Christopher Soto: I am starting to think of myself with less interest in producing “fine art” and more with interest in producing propaganda. I want to make beautiful propaganda via literature. I don’t write from a desire to be included, as a singular individual, in any particular institution, but more so from a desire to move collectively towards a world where nobody is forced to sleep on the streets or in a prison. I believe that literature can create material change and open new worlds that haven’t existed before. What are writers doing, if not moving toward beauty and imagination?

Chung: When we first connected several months ago, you told me that you were planning to bring a suitcase full of your books to El Salvador. How was your launch there? What were your hopes for it?

Soto: Returning to the country of my family, El Salvador, and having a book launch there was one of the biggest honors of my life. There were rooms full of people—poets, artists, queers—at my book launch, many of them extremely brave activists that I have immense respect for.

At the moment there is a state of exception in El Salvador, where constitutional rights do not exist. Today I was reading about Adrián Solórzano, who was arbitrarily detained by the police and then murdered in prison in El Salvador. Many people are scared to speak about the police or government violence because they fear retaliation. In El Salvador, it is nearly impossible to form an abolitionist movement, because the persecution of journalists and dissidents is strong. At my book launch, there were at least two journalists with Pegasus on their phones. This is a hacking program that the Salvadoran government has put onto the phones of dissidents. When I have meetings with leftists in El Salvador, many times our conversations are off the record, and sometimes we have to put our phones in different rooms.

This has happened too in the United States, when friends were hacked by conservative activists years ago, but largely I don’t fear the American government hacking me, though I do understand the history of the FBI harassing Black writers and Communists in the U.S. In the U.S., I more so consider retaliation from right-wing activists at the moment. The right wing is extremely well organized and willing to take bodily risks for their beliefs. There are a lot of similarities between these two countries right now—threats to democracy, police conducting extrajudicial murders, and working-class communities turning toward authoritarian leaders as more democratically inclined politicians fail to address the needs of the most vulnerable. But there are major differences to be noted as well. Being able to think about literary craft and the abolitionist movement transnationally is important to me.

Chung: You’re one of the founders of the Undocupoets campaign, which initially organized to draw attention to the fact that many undocumented poets were and still are unable to apply for some poetry fellowships due to their immigration status. Undocupoets now offers fellowships of its own. Can you speak about what it has meant to you to support the work of undocumented poets and see this campaign grow?

Soto: I’m happy that more undocumented and international writers now have space to share their art via the American publishing industry. It is a huge privilege to have a platform to speak and be able to make some money for your poetry. Not many other places in the world have this privilege. And so it warms my heart to know this is a slightly less heavily guarded door now.

At the moment, though, I am also particularly disinterested in celebrating integration into white-supremacist systems as the end goal for marginalized writers. I am thinking about how we can end billionaires, address poverty and violence globally, and make it so that people aren’t even forced to migrate and wait for inclusion at the feet of white American publishers in the first place.

Writers I know in El Salvador aren’t daydreaming of being celebrated by The New York Times. A lot of great writers I know in El Salvador just want to pay their bills and eat pupusas with their homies—to have a quality of life where they can produce their work and live peacefully in their communities. Yet many folks are always talking about migration and the opportunities that exist elsewhere. I think a better goal would be to tax the rich that prop up the American literary industry and make them pay reparations to writers in developing nations like El Salvador.

Chung: How do you tend to think about community in creative spaces?

Soto: I’m not a big fan of the word community as it pertains to the literary industry. It has been used for emotional and economic manipulation. For example, I have heard people say that I’m mean because I ask to be paid for my work and don’t want to merely build “community” with them. “Literary community” is a whole social and financial economy that exists beyond the creative work or even the person.

At times, people will also use the term literary citizenship in order to describe expectations for free labor. When people speak about good “literary citizenship,” I always wonder: Who is undocumented in this equation? Who does not have the privilege of providing free labor and nepotistic access to others?

I think of most writers I know as acquaintances or work colleagues. There are a handful of writers that I am genuine friends with, but I don’t view them as being part of a literary community with me. They’re just homies. I like reading dead and international poets. Feels less transactional.

Chung: I hear what you’re saying about unpaid labor and what’s expected of authors. Something I often think about how this can also further disadvantage debut writers, marginalized writers, those without as many existing connections in publishing. A different question, then: Are there fellow poets who have been especially influential or encouraging to you?

Soto: Eduardo C. Corral and Ocean Vuong edited the earliest drafts of my book, before it was accepted for publication. They were some of my first friends when I moved to New York City about a decade ago. Eduardo had just released Slow Lightning and then Ocean came to publish his chapbook No. Eduardo and Ocean are phenomenal poets; everyone knows that. Those two as people—I love them both so ridiculously much.

Chung: Now that your book has been out for a few months, are there reader reactions that have been surprising or especially meaningful for you?

Soto: I think that the book is still finding its readers. It’s my debut collection, so it may take a moment to seep into the world. But I trust its craft and the value of its content. With poetry and small-press publishing, there is a lot of reliance on word of mouth. Creative-writing, LGBTQ-studies, Latinx-studies, and Anti-carceral professors are angels for assigning books like mine in their classrooms. I’m trying to steward the book into the world the best I can, while being open to the unpredictability of what can happen with a debut book.

Maybe the most surprising reaction that has happened with the book so far is that a few Hollywood people have stumbled across it. Part of me wants to explore the possibility of collaborating with the film industry. In particular, I think it could be impactful to show the transition from a carceral to postcarceral world via film.

Chung: From one of our early discussions, I know that you are interested in hearing and exploring your family histories. Do you plan to write about this?

Soto: I have been thinking about the American archive as a colonial project—its desire to extract and to document and to categorize everything. This naming of a “thing” can lead to its abuse and exploitation. Sell it!

There are some precolonial spiritual practices that I have been learning in El Salvador. It took me years to earn trust and to be taught a few of these practices, some of which have run through generations in my family. I promised my mentor that I wouldn’t write or share details about these practices. There is some knowledge that shouldn’t be written, even if guarding the practices means it may risk disappearing. I don’t want knowledge to disappear, but I am learning the importance of silence.

There are many private histories in my family and in El Salvador. Silence is a way to stay alive during a war. Some information is not to be sold in a book; it must be learned and earned individually.

Chung: Before we close, do you have any advice for aspiring poets?

Soto: Read internationally. Craft is informed by a poet’s relation to the phonetics of language, but it is also informed by one’s relation to the nation-state. For example, in the U.S. we follow Anglophonic traditions and are influenced by capitalism. But approaches to literature vary internationally: Korean literature has historically been gendered in a way that American literature hasn’t. The publication of South African literature has been racialized in a way that differs from American literature. Salvadoran civil-war poets and Soviet agitprop poets have more in common rhetorically than one might think. Read internationally so that you know craft is nebulous and the rules are meant to be broken. Break all the rules you can, in order to speak local experience into the global struggles for liberation.