The Good News About the Holocaust (Education) in America

The untold success story you’d never know about from the headlines

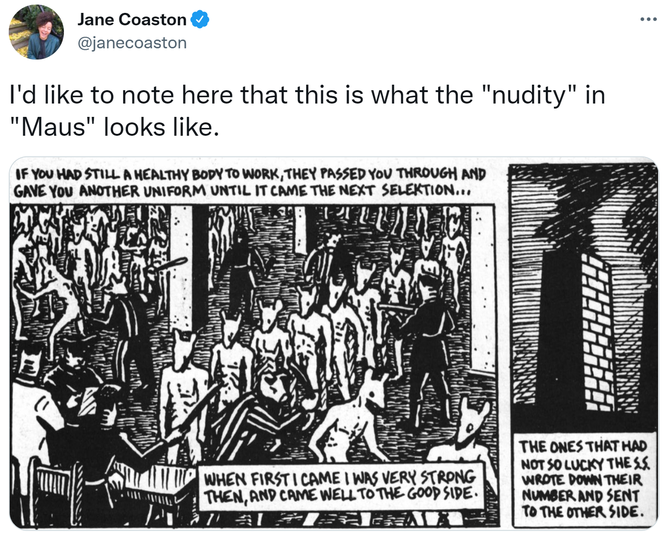

Today is International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Recently, a school board in Tennessee decided to mark the impending occasion by cleansing their eighth-grade curriculum of Maus, a graphic novel that illustrates the Holocaust using cartoon mice, over concerns about the Pulitzer-winning work’s inappropriate inclusion of profanity and nudity.

It is indeed a shame that the Jews of Europe did not have the foresight to die in a more family-friendly fashion. One hopes that the school board will find a more wholesome way to discuss the Nazi genocide. But dim-witted districts aside, what is the state of Holocaust education in America? Judging by the headlines that appear every year, you could be forgiven for thinking that things are pretty terrible.

“Nearly two-thirds of US young adults unaware 6m Jews killed in the Holocaust,” The Guardian reported in 2020. “According to survey of adults 18-39, 23% said they believed the Holocaust was a myth, had been exaggerated or they weren’t sure.”

“Survey finds ‘shocking’ lack of Holocaust knowledge among millennials and Gen Z,” NBC wrote of the same study. “Over half of those thought the toll was under 2 million.”

“What do Americans know about the Holocaust? Some, not much,” said the Religion News Service of a different survey that same year. “A new Pew Research Center poll shows Americans generally know what the Holocaust was, but fewer than half can correctly cite the number of Jews killed in the Holocaust—6 million.”

“Asked to identify what Auschwitz is,” The Washington Post reported in 2018, “41 percent … could not come up with a correct response identifying it as a concentration camp or extermination camp.”

This sounds awful—until you discover what Americans know, or rather don’t know, about other things. According to a 2016 survey reported on by Voice of America, “Roughly 60 percent of college graduates couldn’t correctly name a requirement for the ratification of a constitutional amendment, and 40 percent didn’t know Congress has the constitutional authority to declare war. Not even half know that the Senate oversees presidential impeachments.” (Presumably, they’ve figured that one out since.)

When we move from college grads to all American adults, the results get even worse. 37 percent don’t know when Election Day occurs every four years. Over half don’t know that Franklin D. Roosevelt spearheaded the New Deal. (This is setting aside the 18 percent in another survey who think it was composed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.) Over 60 percent of respondents do not know the term lengths for senators and members of the House of Representatives. In 2021, the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania found that nearly half of American adults could not name all three branches of government. The list goes on: Half of Americans don’t know that the Supreme Court can overrule the president on constitutional questions. 64 percent don’t know that the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery.

Put in this context, what Americans know about the Holocaust is actually quite impressive. According to Pew’s 2020 study:

When asked to describe in their own words what the Holocaust was, more than eight-in-ten Americans mention the attempted annihilation of the Jewish people or other related topics, such as concentration or death camps, Hitler, or the Nazis. Seven-in-ten know that the Holocaust happened between 1930 and 1950. And close to two-thirds know that Nazi-created ghettos were parts of a city or town where Jews were forced to live.

In other words, Americans demonstrate greater literacy about the Holocaust—an event that happened to a tiny fraction of the world’s population on a completely different continent—than they do about their own country’s institutions and history. More Americans can identify Auschwitz than their own branches of government. Tellingly, Americans across the ideological spectrum regularly make and debate Holocaust analogies, because its story is one of the few touchstones they all share. Far from a failure, Holocaust education in America has been a triumph, piercing the veil of civic ignorance that obscures so many other subjects in the popular consciousness.

We have the entire year to worry about fading historical memory and corroding collective concern about the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. But today, I think it’s worth pausing for a moment to appreciate the extraordinary efforts of the exceptional educators—including many Holocaust survivors themselves—who accomplished this feat. Through curricula, museums, books, testimony, television, and film, these tireless teachers have achieved something few others have managed.

Perhaps it’s also time we learned from their example. Once we’ve allowed ourselves to acknowledge the success of Holocaust education, we might turn those same talents and resources to other areas that have long been neglected—from educating society about the true nature and substance of anti-Semitism to teaching the world to respect living Jews, not just venerate dead ones.

Those of us who care about educating the next generation about the perils of prejudice have a greater ability to open minds than we realize. We should make the most of it.

Further Reading: How to Explain the Holocaust in One Simple Statistic

This is a free edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the intersection of politics, culture, and religion. You can sign up here to get future free editions in your inbox. But to get access to all editions, including exclusive subscriber posts, and to support this work, please subscribe to The Atlantic here.