Opening Up the Hip-Hop Vault

Some recent celebrations of the art form ruthlessly prune its complex history.

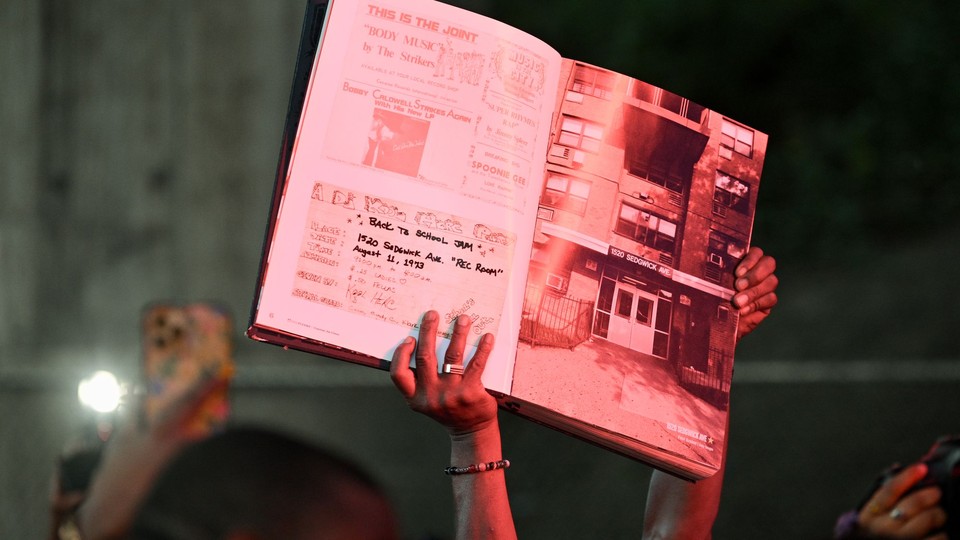

Over the past several weeks, music fans and media outlets have celebrated 50 years of hip-hop. Its beginning is widely attributed to a party in the Bronx on August 11, 1973, when DJ Kool Herc played breakbeats in rapid succession on two turntables. But how do you name a single origin point of an art form, any art form? That party at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue represents a choice about how to tell the story of the music—and a good one. But all stories are worth complicating. Hip-hop is the child of many influences, and has expanded to many regions and styles.

One obvious detail that often gets lost is that there are currently four generations laying claim to hip-hop. Although my own, Generation X, often functions as the gang of grumpy elders—yelling at the youngsters to get off our collective lawn and bragging wistfully about the music’s golden age, to the annoyance of Gen Z—we are in fact not the eldest in hip-hop. The first generation in hip hop was the Baby Boomers, young Black people of the Americas who came of age amid the Black Power movement, decolonization, and a truly global discourse on Black liberation. At the same time, the backlash to that moment was being ginned up: In the 1970s, incarceration skyrocketed and deindustrialization devastated cities. It makes sense that hip-hop would emerge from young people raised with a deep sense of possibility and an immediate experience of dashed hope. The music that resulted from these young people living at the margins of a metropole, descendants of Black Americans who had been enslaved, Jim Crowed, and colonized, was not a sonic melting pot but a cultural gumbo, or maybe even a bricolage of everything they brought with them—most of all, culture.

Poor people are rarely described as cosmopolitan, but they often are, especially in places like New York. I’ve argued that the role of the South in the beginnings of hip-hop has been terribly discounted, and a number of important scholars such as Regina Bradley and Zandria Robinson are arguing for the South as a central site in the development of the form. The rhyming ballads of the deep South of the 1930s and ’40s are completely recognizable as “rap.” These ballads shaped African American disk-jockey culture, in which popular deejays would rhyme between songs. This practice influenced Jamaican chatting, which became a foundation for hip-hop in the Bronx. Cycles like this one are present throughout the art form—in dance, in language, and in style, all part of what the scholar Paul Gilroy famously called the flows of the “Black Atlantic.”

But while these cycles are essential to our historical and ethnomusicological understanding, at the local level they were often of minimal importance, because hip-hop in African diasporic communities always had a grounded immediacy. What was happening here and now, wherever here and now was, was the art form’s primary concern. That is easy to lose sight of now that hip-hop is a global, multibillion-dollar industry. But hip-hop artists will never let you forget where they come from and what that means socially, politically, and culturally.

Hip-hop also has so many subgenres, some of which came of age alongside it, others that were born through distinct local spaces: go-go, crunk, bass, hyphy, house (a different yet deeply connected form, like go-go), gangsta rap, trip hop, chopped and screwed, bounce, drill, and Trap. In the generational and regional wars of hip-hop, entire subgenres are often dismissed as poor derivatives or as inauthentic. Indeed, some of the recent celebrations seem to treat the evolution of hip-hop music in a linear, chronological fashion, ruthlessly pruning along the way. But if hip-hop is to remain aesthetically compelling and artistically meaningful, and if we are to tell its story truthfully, we must acknowledge its breadth and depth, its different sensibilities and its many beginnings. This moment of celebration should elicit curiosity rather than deepen canonization. Let’s open up the vault and recognize why this form that many critics hoped and believed would die is still strong and growing after 50-plus years.