We Read the Banned Books

To defeat the forces of exclusion, one must pursue that which has been prohibited.

It is easy to grow cynical during Black History Month. From corporations to educational institutions, it can feel as though the annual chorus of tributes is hollow, especially given the persistence of racism and how often it isn’t remedied. And this year, we remain in a period of intense backlash against the study of Black literature, history, and culture as state legislatures and pundits mock our traditions as “wokeism.” At times, I wish that some of those who come to the table to celebrate with us would spend more time going to battle against those who would remove us from every classroom, bookshelf, and historical archive.

Nevertheless, I understand that Black History Month remains significant. I find myself, in the lectures I’m giving this year, lingering on this: Once upon a time, in the antebellum United States, it was illegal for enslaved people to learn to read. For that transgression, they could be punished by death, maiming, or being sold away from their family. Yet enslaved people still endeavored by any means possible to become literate. And of course, after emancipation, freedpeople flooded into schools; in the late 19th century, a cadre of Black educators and scholars worked valiantly to write themselves into a history that had excluded them.

The point is that struggling against those who would keep us from learning and from being studied—and by us, I mean Black people here, but also all marginalized people—is nothing new in this country’s history. The forces of exclusion are old and resilient. Then, as now, the only way to defeat them is to pursue that which has been prohibited. We read the banned books, we study the verboten topics, and we share them, still.

At the beginning of this Black History Month, I returned home to Alabama for a Pen America program. I was in conversation with two brilliant young Black women writers, Tania De’Shawn and B.J. Wright, at the campus where my parents first met as professors, Miles College. The room was filled with family, friends, students, and community members. It was a beautiful homecoming for me, aligned with an organization that celebrates freedom of expression and the long tradition of African American literary culture in Alabama.

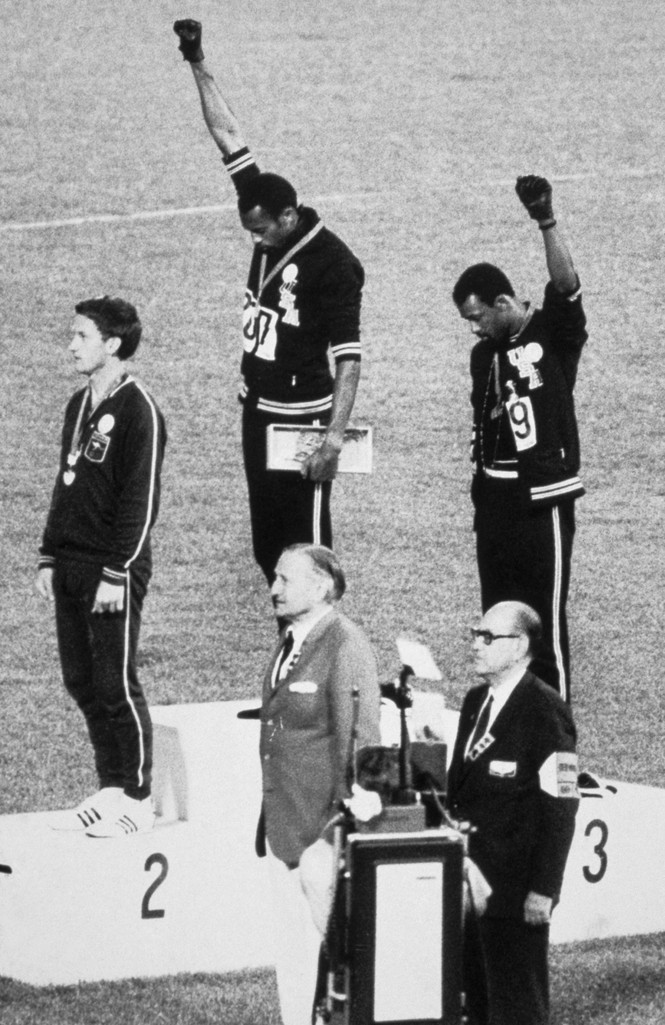

But that same week, the public-school system in Hoover, Alabama, had canceled visits from Derrick Barnes for his young-adult book Victory. Stand!: Raising My Fist for Justice, co-written with Dawud Anyabwile and Tommie Smith, which tells the story of the Black American track athlete Tommie Smith’s protest at the 1968 Olympics. The school system claims that the events’ cancellation was a consequence of an unsigned contract, but I had a very strong suspicion that the decision was in retaliation for Barnes speaking out publicly against racism. (A parent reportedly complained to a local school principal about Barnes posting “controversial ideas” on social media.)

When I saw Barnes in New York for the National Book Awards in November, he generously introduced me to Tommie Smith. I was a bit starstruck, but I got up the nerve to tell Mr. Smith that my (adoptive) father had been inspired to become politically engaged by his action at the ’68 Olympics, and that it was one of the direct inspirations for him to move to Alabama—where he met me and my mother. I thanked him for that with tears in my eyes.

The history in Victory. Stand! is important to my own life and to the story of this nation. And although I have no control over the Hoover City School District, I believe in the power of telling the truth with my words and acknowledge truth-tellers such as Barnes, Smith, and Anyabwile—especially those who write for the children.

Happy Black History Month!