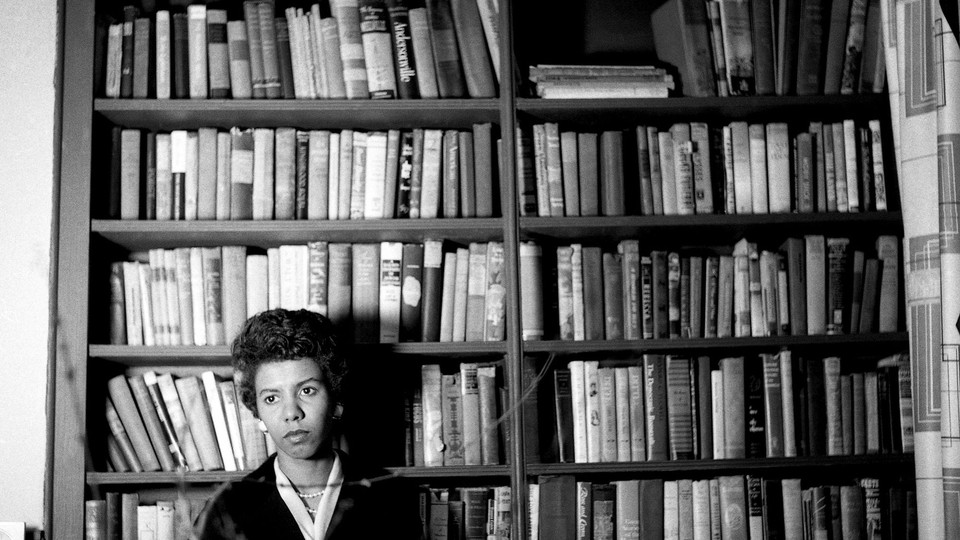

Revisiting ‘A Raisin in the Sun’

The dynamism of theater reframes Lorraine Hansberry’s foundational work with new urgency.

Last Friday I saw A Raisin in the Sun directed by Robert O’Hara at the Public Theater in New York City. A new friend, Tanaïs (who won the Kirkus Prize in nonfiction this week for her gorgeous book, In Sensorium: Notes for My People), had invited me, and in a bit of kismet, I was also asked by the Lorraine Hansberry Initiative to participate in a talkback with filmmaker Tracy Heather Strain after the show.

Because I wrote a biography of its author, Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun holds a special place in my heart, of course. But I was not expecting to be so deeply moved by this version of the play. It is the closest to Lorraine’s vision that I have ever seen. The actors sound right, in tone and cadence, for the South Side of Chicago setting. I would learn afterward that the cast is almost entirely composed of midwesterners. The staging is a cramped kitchenette apartment, showing wear and decay. The actors frequently speak simultaneously, giving a feeling of urgency and authenticity—families talk over each other. And nerves, desire, and rage are captured with the subtlety of stances, curling cigarette smoke, and gentle caresses. It is simply breathtaking.

There are moments of artistic license. But every choice serves Hansberry’s vision. In 1959, When A Raisin in the Sun was first on Broadway, she found herself combatting some serious misperceptions of the play. She was misquoted by a critic as having said it was just an “American” play and not a “Negro” play, when in fact she intended it not only as a Black play, but as a specifically Chicago-Black-working-class play.

People were all too happy to read Hansberry’s play as a story of middle-class aspiration, an assimilationist dream about Black people using an insurance check to move into a nice white neighborhood, when in fact Hansberry wanted theatergoers to understand the depth of the injustice experienced by the Younger family. At the conclusion of the play, though they are integrating a white neighborhood, that integration almost certainly promises to be a painful and even violent encounter.

When Hansberry had the opportunity to write the screenplay for the film version of A Raisin in the Sun, she sought to correct common misinterpretations of the play by adding scenes that would make the living conditions on the South Side, and the political stakes of the work, clear. But her additions, and the film footage of them, wound up on the cutting-room floor—to her immense frustration. Although there are three versions of the film, we have yet to see one that is as Hansberry intended it. Her other screenplays have not been made into films at all.

Theater is collaborative art. A production is shaped not only by every participant, but also by the moment of each performance. Its dynamism is one of its virtues. But audiences don’t always agree. Tonya Pinkins, a distinguished Broadway and television actor as well as filmmaker who plays Lena Younger in the new A Raisin in the Sun revival, told me that there are some people who are upset about this grittier—and arguably more authentic—rendering of Hansberry’s play. I suppose that is to be expected, although I’d much rather see a version that adheres to Hansberry’s aspirations than theatergoers’ comfort.

For better or worse, the dynamism of theater also shapes its critical interpretation. Among Hansberry’s points of frustration over how A Raisin in the Sun was received was that critics failed to see a connection between her character Walter Lee and Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman. As I wrote in my Hansberry biography, Looking for Lorraine, this was because audiences couldn’t help but see Walter as an exotic character, “the image of the simply lovable and glandular Negro”; there is a certain poetry in the fact that, at present, there is a staging of Death of a Salesman on Broadway starring Wendell Pierce and an entirely Black principal cast.

Hansberry’s caveat to her disapproval of critics’ failure to see the relation between Willy and Walter was that she believed she had failed to make Walter a sufficiently central character. As a critic myself, however, I don’t see this as a weakness of A Raisin in the Sun, but rather a strength. It is a masterful ensemble, populated mostly by women—a choice that I view as something Hansberry’s before-her-time feminism led her to make, despite herself.

And it is a timeless choice. Patriarchy, along with housing insecurity, classism, poverty, residential segregation, employment discrimination, reproductive rights, educational inequality, and neocolonial arrangements in Africa, are all as relevant today as they were in 1959. In O’Hara’s direction of Hansberry’s play, this inadvertent virtue—the centrality of women—is highlighted. Lena, Ruth, and Beneatha, each brilliantly performed, are all as captivating as Walter Lee, the late Mr. Younger (who appears in this version as a spectral presence), and the beloved grandson Travis.

This New York theater season, both on and off Broadway, is filled with Blackness. That is, I assume, evidence of how the murder of George Floyd inspired artists. Most of us are far afield of the New York stage, but my experience last weekend (I also saw the Public’s rendering of the historic debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union, which took place six weeks after the 1965 death of Hansberry, Baldwin’s dear friend) reaffirmed for me the value of live art wherever we can find it.

Living encounters are where we rehearse our values. Sometimes they’re challenging and sometimes they’re inspiring. I often say that Lorraine Hansberry changed my life. Writing about her expanded my creative voice. But she also changed me as a person, helping me understand the value of bringing my words past the page to people, not with the goal of being feted but in the hopes that they will be chewed on and maybe even (if I’m very lucky) transformed into action.