The Rite of Spiritual Hygiene

Four things I’ve watched and read that provide a blueprint for life—and for hope.

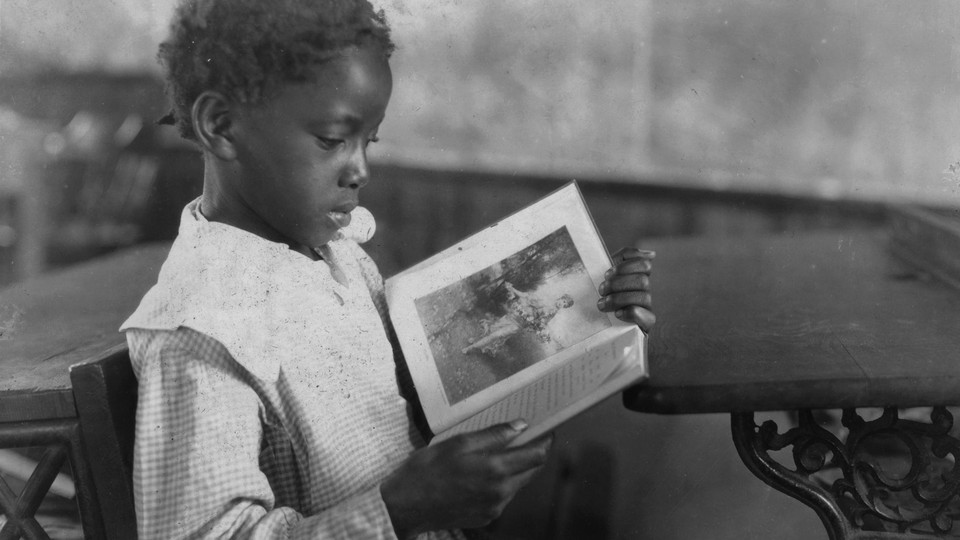

One of the things people often ask me is “How do you find time to read?”—or, for that matter, take in art, theater, and music. My knee-jerk response—which I withhold because I don’t want to be rude—is “How do you live without it?” And I mean that literally. These rituals keep me steady, and I know I’ve chosen the correct profession because I consider reading and absorbing culture to be forms of spiritual hygiene. Not escapist, mind you; every good work of art says something profound and usually painful about the human condition. But art also allows us to step back from the world to reflect and assess. Most of all, it begs us each to consider what our legacy will be in relation to our societies.

On that note, this Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I offer a few recommendations. In the course I co-teach with Eddie S. Glaude Jr., “African American Studies and the Philosophy of Race,” we recently had students read the historian Nell Irvin Painter’s classic article “Soul Murder and Slavery.” In it, Painter details the violence endemic to the peculiar institution. She describes the layering of physical and emotional violence in the lives of the enslaved, but also how this violence became baked into the culture of slave societies; Painter understands this legacy as part of why southern states remain those with the highest rates of physical violence. Painter’s essay is important for understanding the history and culture of the United States, of course. But it is also an insightful testament to the power of habit, its inheritability, and how it shapes who we are.

I also teach a course titled “Diversity in Black America,” in which my students and I recently watched the writer-director Rebeca Huntt’s auto-ethnographic film, Beba. The 2021 documentary details Huntt’s coming of age in New York as the daughter of immigrants from Venezuela and the Dominican Republic, and the way she and her siblings navigate inheritances of mental illness, colonialism, and their familial slave societies of origin in Latin America as well as in the U.S. It is a bold and recursive work of art; it is beautiful, yet it hurts to watch.

Inherited legacies are also central to Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s new series, Making Black America, which premiered last week on PBS. It details the process of building cultural, social, and political institutions behind what W. E. B. Du Bois called “the veil” of race in the United States. To riff on lines of verse by the intellectual, writer, lawyer and NAACP Secretary General James Weldon Johnson, “[African Americans] built them a world,” notwithstanding the inheritance and persistence of violence and cruelty. It is a gorgeous story of human resilience that warrants recognition.

My out-of-work reading at present is Abdulrazak Gurnah’s stunning Afterlives. The novelist (who received the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature) captures the brutal impact of German colonialism on his native Tanzania, and a family’s efforts at repair and love in the face of its violence. The book’s protagonist, Ilyas, lives a life that is shaped by the immediacy of the German occupation as well as by the global position of his society’s colonizers. A masterpiece, Afterlives shows us that fascism is never a singular project, and that violence always reaches beyond its immediate target.

A line from Huntt in Beba—“God, bring me back Black every time”—gives me chills. I don’t hear Huntt’s declaration as racial essentialism; she isn’t asserting the superiority of Blackness or some genetic magic that comes from it. Rather, I hear it as the beauty of dreaming from the underside—and, furthermore, in creating from that place.

I teach African American studies, but as readers of this newsletter know, I read and study globally. The consistent theme is that I’m interested in listening to the underside, which accounts for most of human experience, given how many generations of stratification we’ve lived with. Life is hard. Hope is harder. But we’re here to participate in both. Reading and consuming art are, as far as I am concerned, akin to prayer—indispensable rituals for holding on to possibility.