The Reaping Season Is Upon Us

Sixty-five years after the Little Rock Nine made history, a water crisis in Jackson shows the enduring damage of an ugly past

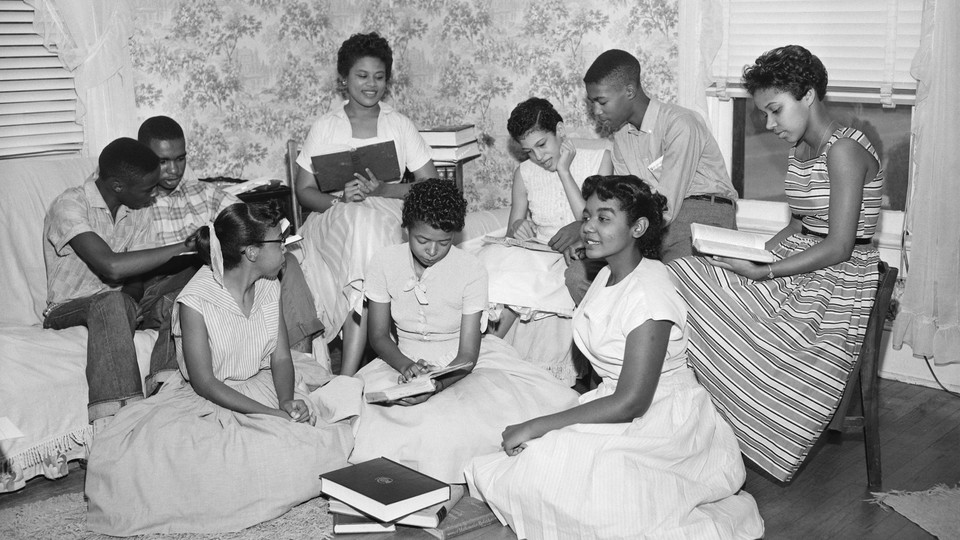

Sixty-five years ago this week, nine Black students desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The students, who came to be known as the Little Rock Nine, were initially blocked from entering the building by the Arkansas National Guard. In reaction, President Dwight D. Eisenhower brought the National Guard under federal control and commanded them to escort the students into the school. The students faced a screaming mob and threats. It was one of the hallmark events of the civil-rights movement, a vivid example of the massive white resistance to desegregation.

We often reference such events by noting that many of the actors of that time are still with us, veterans of the civil-rights movement and their tormentors alike. In the classroom, I tell my students stories about my own mother’s coming-of-age in Jim Crow Alabama. The point I and others often make is that these events are not as distant as we might be inclined to think. Over the years, however, I have grown to believe that this framing is missing something.

About 15 years ago, I taught a student in a constitutional-law class who had graduated from Central High School nearly a half century after the Little Rock Nine first entered its doors. She described how, despite the fact that the school was superficially integrated, its classrooms and social activities remained completely segregated, with Black students concentrated in academic tracks that did not lead to college or professional careers. I wasn’t surprised. But I realized that she, a young person, could tell the aftermath story of the Little Rock Nine by testifying to the persistence of segregation decades after the troops and cameras had left. Together, we could read from her present into the past.

I had a similar experience teaching a 2005 article titled “The New White Flight” in a critical-race-theory course at University of Pennsylvania School of Law. The article documented white families choosing to leave excellent schools in Silicon Valley that had significant numbers of Asian American students, citing a competitive disadvantage. There was an apparent panic over the loss of the privileges conventionally accorded to whiteness. As we discussed the article in class, several students commented that a kid who was quoted in the article was also a student at Penn. We invited him to attend the next session, where he described the complexities of race, class, and networking that shaped achievement and access in his home community. This student had recent experiences that facilitated our discussions of the multigenerational experience of anti-Asian racism in the United States, evidenced in legislation, social practices, and policy regarding schools and property ownership.

I offer these modest examples to suggest a perspective shift. Rather than reminding young people that the horrors of the past aren’t so distant, educators and elders bear a responsibility to meet them with the crises and conundrums of our moment, and to work alongside them to understand how they came to be and how we might imagine a different way of being with one another.

These grim learning opportunities unfortunately abound. Last week, national attention turned to Jackson, Mississippi, the capital city of the poorest state in the Union. A city with a distinguished tradition of civil-rights activism and organizing, Jackson is currently without safe water for drinking, bathing, flushing toilets, or brushing teeth—the result of government failure to maintain aging public infrastructure. Having been in Jackson just a few weeks ago, I can assure you that it is no surprise to local residents— 82.5 percent of whom are Black—that they bear two burdens: brutal retaliation for their history of resistance to Jim Crow and white supremacy, and horrifying neglect from the elites of the state. As the descendants of those who labored to make cotton King (and the United States wealthy), Jacksonians are well-versed in the ongoing practices of domination and exploitation.

Similar catastrophe has unfolded in Pakistan, where a third of the country is flooded; as in Jackson, people are suffering because of the indulgences of others. In the case of Pakistan, it is the environmental negligence of wealthier countries that has precipitated this disaster. In every corner of the globe, the unequal distribution of suffering today has a relevant historic backdrop.

Simply put, our harrowing present is a reaping season.