How to Be an Honest Historian

To be a responsible student of history, I must contend with defenses of true ugliness—and hold my admiration and dismay at once.

When I was a student, I didn’t like history class. My aversion to “history” as an academic subject was so great that even when I enrolled in a doctoral program called “The History of American Civilization,” I didn’t really think of myself as training to be a historian. I eventually embraced what I took to be the softer term cultural historian, deciding that what I had learned in college and in my doctoral program could apply to the study of historical events without applying conventional history methodologies.

As a thoroughgoing archives junkie in adulthood, my earlier disdain for history class feels curious. In truth, it was because I didn’t like memorization. Fact-based learning bored me, as did the study of war and details about the lives of extremely powerful people. As an adult, I’ve found that the things I love about the study of the past do depend on detailed facts, but the impetus isn’t knowing facts for facts’ sake. Rather, I focus on assessing relationships between groups of people and forming ideas about those relationships, what makes them right or wrong; how they are shaped by land, technology, militarism, wealth, and ideology; and how people dreamed up new ways of being in relation to one another, using art and intellect.

At this historic juncture, teaching history through the study of human relationships is paramount. But that requires all of us, even people who are politically strident—as I admit myself to be—to engage in an earnest and open dialogue about what constitutes a good society and fair treatment. And it also means stomaching some disturbing thoughts. I know that to be a responsible student of history, I must contend with defenses of ugliness (case in point, the near-constant praise of Founding Fathers who were slaveholders.)

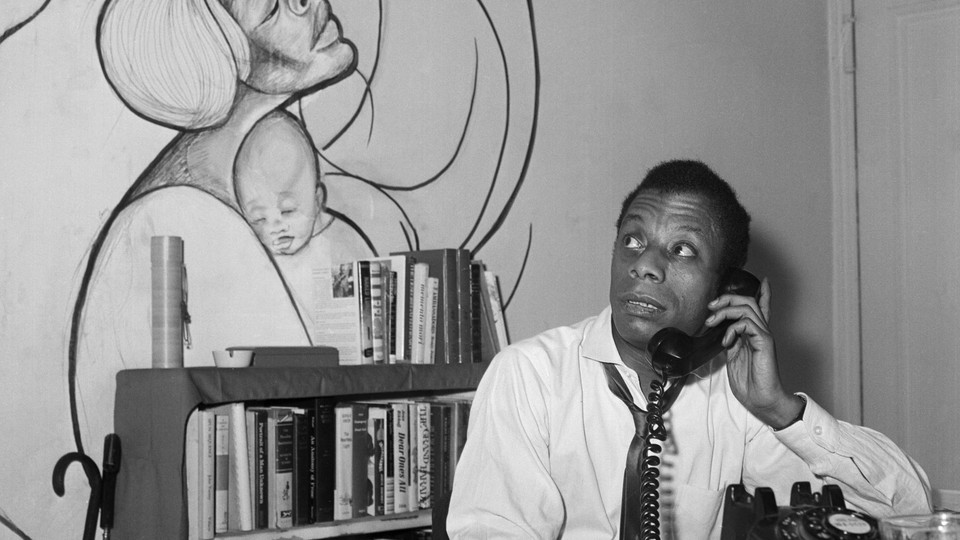

My engagement with these defenses is not a sign of dispassion, reason, or politeness as a virtue. Instead, I engage because disagreement at its best is not just dismissal, especially when one doesn’t want to throw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. I was reminded of this recently when thinking about the great poet, critic, and professor Sterling Brown. Brown was a brilliant celebrant of the Black southern vernacular tradition. He was the man James Baldwin once said he would emulate if he were ever a professor (and since he did ultimately teach at UMass Amherst, one imagines he did take on Brown’s ways). Brown was also a mean-spirited homophobe who seemed to revel in insulting gay men. I imagine he didn’t show this side directly to Baldwin, but I also imagine it stung mightily when Baldwin read Brown’s ugly words.

Rather than go to a knee-jerk defense of him as a man of his time, I have to hold my admiration and dismay at once and decide what to do with them. I also have to accept that, whatever I do with those rivaling feelings, there will be people from various perspectives who find my account unsatisfactory. There are plenty who would defend Brown at his worst. Where I have settled, however, is that I will continue to read and praise Brown, but I will also tell the truth about what I find offensive and unacceptable in his work. I do this not only to mark my values, but also because I want to learn how to identify my own failures. Looking at him, and at so many other examples of the misdeeds of people I admire, I ask myself, what injustices am I propping up even as I think I’m fighting other injustices?

Case in point: It took me far too long to understand how central transphobia is to patriarchy and the ideology of white supremacy, and therefore how central trans liberation is to my own freedom dreaming. Though it is obvious to me now, given how intensive the attack on trans people is in the midst of the current rise of authoritarianism and fascism, it should have long been obvious, as I came of age in the ’80s, a period filled with routine mockery of Black trans women in popular culture. It is particularly bad that I didn’t get it as someone who was raised to reject homophobia, in addition to racism and sexism. But willful ignorance about injustice is an American habit, even among those of us who experience injustices. And despite myself, I am thoroughly American. Humility is something I have to learn.

In short, if I can proclaim a movement’s legacy proudly, I must also be willing to admit a movement’s narrowness with some shame. I have watched too many people justify such narrowness over the past few weeks in the names of feminism and civil rights. But it’s not enough to point a finger; I must also look in the mirror. And these days, in my archival explorations, I don’t just look at historical actors rigorously and critically. I look at myself with the same care, insisting that the uses of history (and memory) include unabashed and honest reflection.