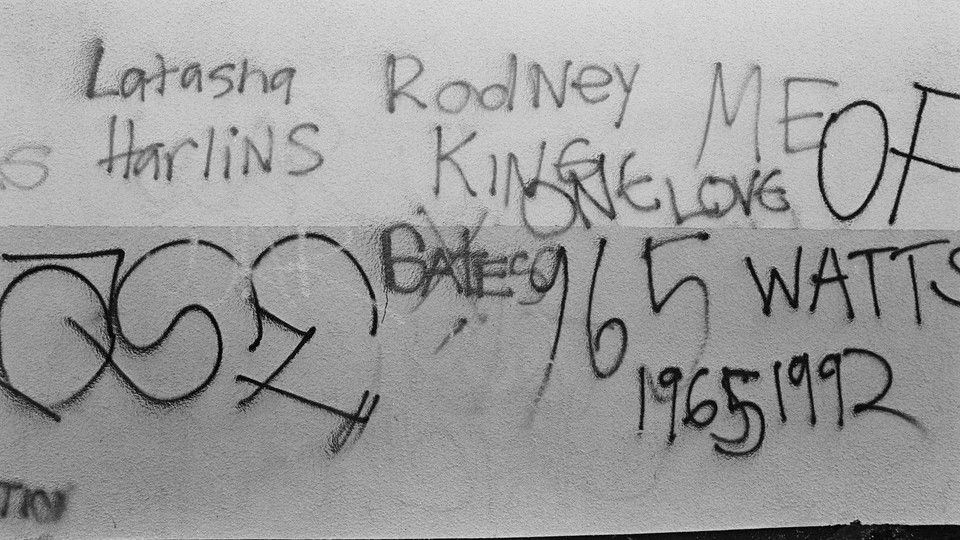

Rodney King, 30 Years Later

Three decades ago this week, the officers on trial for beating King were exonerated. Today, the horror has become mundane.

Thirty years ago this week, the police officers who were on trial for beating Rodney King were exonerated, and Los Angeles went into revolt. The outrage seems so pure in retrospect, and the sense of betrayal so naive. It was a horrible beating. Yet today one is tempted to say, But he lived!

It was the beginning of our current era, in which video footage serves as evidence for state violence against Black people. This era might promise validation of claims of racial injustice, but it also threatens to simply codify this injustice as an acceptable American fact. Consequences are rare and collective grief is ordinary.

Rodney King pleaded, “Can’t we all just get along?” The answer, in short, has been no. These days the footage extends far beyond group beatings to killings: gunshots into a car, into a back, into a child, and flesh-to-flesh suffocation. The exoneration of police officers remains the rule rather than the exception. What kind of people would quietly accept this from a government that is obligated to protect them?

I was a college student 30 years ago on the night the verdict was read. A small group of friends and I called a campus rally, which we held on a plaza once distinguished for anti–Vietnam War and anti-apartheid protests. I have no memory of doing so, but apparently I led an expletive-filled chant directed at the president of the university. What I do remember is that I made a connection that night. At our freshman orientation, the dean had made a speech defending the West and its canon against the encroachment of multiculturalism. I connected that disturbing moment to the tendency of our fellow students to slam campus gates in Black students’ faces, assuming we were locals from the largely poor Black community in New Haven. I connected this juxtaposition between the rich university and the neglected Black city to King’s experience being cowed with clubs by a group of swaggering officers.

Several years later, at my law school orientation, a distinguished professor delivered a lecture about the famous trial. He showed us the footage of King being beaten. And he narrated alongside it, “Do you see how King keeps getting up? They are commanding that he stay down and he won’t comply, he just keeps getting up!” The point, I gathered, was that effective lawyering could change how you see and therefore interpret things. He asked if anyone had a different perspective than they had had before. Most of the class raised their hand. I held mine down, enraged.

Thirty years later, no matter how horrifying a killing is, justifications are still made. No matter how ubiquitous cameraphones are, excuses are given for why what we see plain as day is not in fact what is happening—not only by defense attorneys, but also by politicians and news stations. These excuses often hinge upon what is considered to be “knowledge”: about the habits of Black people, and about the details of the case coming from official police reports. Over the past decade, however, something has shifted. Skepticism about these justifications has extended far beyond Black social worlds. But the tragedy repeats nevertheless. Convictions are rare, and death is routine. Strategies are elusive. How do we stop the killings?

Many of us know better, but collectively we aren’t yet doing better. And this is part of why the attack on knowledge in the form of banning books and turning critical race theory into a fictionalized threat is so insidious. Knowledge is a potential challenge to the status quo and the mythologies that sustain it. There are people who are hell-bent on the country not knowing—and therefore not doing—better when it comes to injustice.

Thirty years ago was the beginning of an era. Evidence hasn’t been enough. Ten years ago Rodney King died, and so did Trayvon Martin from the violence of a vigilante who wanted to be a cop. And more deaths came, along with more footage. The country is teeming with evidence of state violence. Yet Black people continue to be struck down by officers, and what is horrifying is becoming mundane, yet again. It is a heartbreaking retrospective.

But do you see how we just keep getting back up?