Valerie Boyd and the Tradition of Creativity and Care

In Memoriam for a key figure in Black Women's Literature.

This is a free edition of Unsettled Territory, a newsletter about culture, law, history, and finding meaning in the mundane. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. For access to all editions of the newsletter, including subscriber-only exclusives, subscribe to The Atlantic.

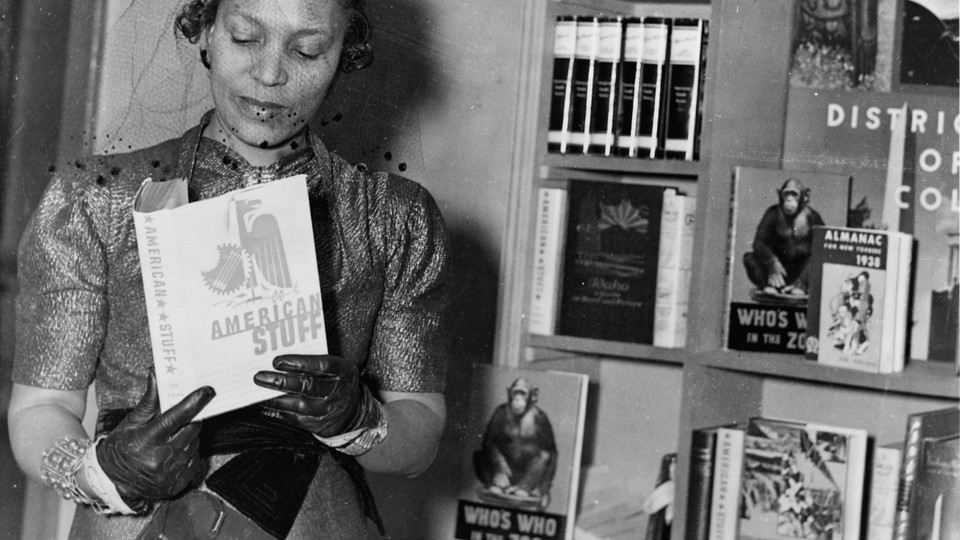

The writer Valerie Boyd died last week. In my world—Black and southern writers, scholars of Black studies, and Black women readers—there was an immediate collective grief. A sorrowfulness and shock lay thick on our communications. I didn’t know her well, but I felt her presence and benefited greatly from it. In 2003, when she published Wrapped in Rainbows, a comprehensive biography of one of the greatest American writers, Zora Neale Hurston, I was astonished. Here was a Black woman writer taking up the story of another Black woman writer, narrating it fully despite all of the confusion and evasion surrounding Hurston’s life. To lay claim to another’s story is an act of faith and boldness at once. And more than that, Hurston was and is so beloved, a misstep in the telling could have been a disaster. Eyes were watching Boyd.

Boyd more than met the challenge. Wrapped in Rainbows is a breathtaking portrait that stands tall alongside the homages to Hurston’s work, even Hurston’s work itself. It provided a model for me when writing about Lorraine Hansberry. And although I was writing what I called a third-person memoir rather than a comprehensive biography—a thematic portrait of an artist, intellectual, and activist—Boyd’s careful nod when I told her about that project was all the affirmation I needed to write the book. We met by happenstance at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture that day (it was a remarkable day in so many ways) and then I turned my face back down to Hansberry’s handwritten pages, heart full.

Boyd’s life is a reminder that so much of the Black women’s literary tradition is a dance between creativity—the heartbeat of art—and recuperative care. We tell neglected stories of the women who preceded us. We invoke them when they are insufficiently cited. We return to them for wisdom and brilliance. Boyd did that; we must do it for her. And as the generations continue, the work continues, as does our responsibility to the tradition.

Last week, I was in Atlanta in conversation with Beverly Guy-Sheftall, the Anna Julia Cooper Professor of Women’s Studies at Spelman College. She graciously joined me in conversation about South to America. Guy-Sheftall, among other distinctions, compiled the first major historically organized anthology of African American feminist thought, titled Words of Fire, in 1995. At our meeting, she said beautiful words honoring Boyd. And I recalled that she had anthologized Hansberry in Words of Fire. And she had been there on that day in the Schomburg. These encounters with history, and each other, repeat for a reason. We live in the tradition we are maintaining.

We have gathering places and rituals that bring us together, as well as work that follows a common purpose. We join and depart, expecting to join again, hearts dashed when we realize it won’t happen in this lifetime. A few weeks ago, I emailed with Rebecca Walker, with whom I once worked on a wonderfully strange undergraduate student journal, and expressed excitement about her mother Alice Walker’s forthcoming book, Gathering Blossoms Under Fire: The Journals of Alice Walker, which was edited by Boyd. Alice Walker had been there on that day in the Schomburg as well. The next message I sent Rebecca was one of condolence.

The last message I received from Valerie was about the Chesapeake section of South to America. Recalling the grace in her message, I think about how Farah Griffin said, so succinctly and beautifully about Boyd, a dear friend: “She was one of the most generous people I’ve ever known.”

Time moves on. In Atlanta, Valerie’s hometown, there was a group of Spelman undergraduates in the audience. One of them asked a question so gorgeously framed that I dare not even try to replicate it. But the gist was about how we seek to be remembered and by whom. I fumbled in my response, but in retrospect the answer is: in this tradition that has held me close, and by young women like her.