Black History Is Also Labor History

What Starbucks workers’ unionization efforts have to do with Black History Month

This is a free edition of Unsettled Territory, a newsletter about culture, law, history, and finding meaning in the mundane. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. For access to all editions of the newsletter, including subscriber-only exclusives, subscribe to The Atlantic.

On February 9, while scrolling through Twitter, I saw a flurry of posts saying that Starbucks had fired workers who were organizing a union in Memphis. (Starbucks said the employees had violated multiple company policies.) After reading several articles about the event, I also noticed social-media comments about the tragic irony of their dismissal during Black History Month, in Memphis of all places. After all, Martin Luther King Jr., arguably the most widely celebrated African American during Black History Month, was killed in Memphis. He was there supporting Black sanitation workers on strike due to unequal and terrible working conditions.

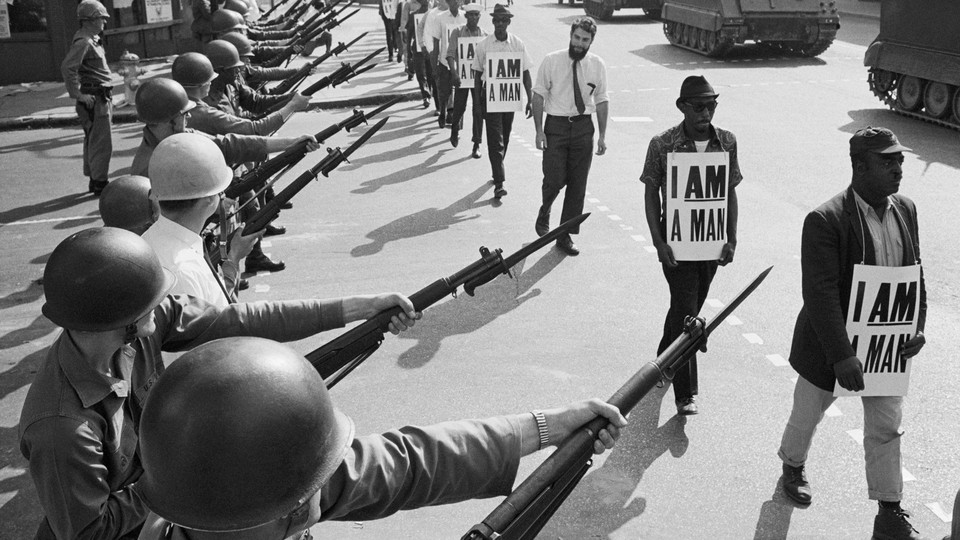

Corporations, Starbucks included, have taken on Black History Month celebrations in a fashion that, more often than not, seems like public-relations virtue signaling. They offer palatable, feel-good moments, but don’t often go very deep into the content. They rarely include historical details about topics such as the experience of Black sanitation workers in Memphis. While the white workers rode in the truck cabs, the Black workers rode standing on the back, and were paid less. In all kinds of weather, Black workers labored alongside maggots and rats. In February of 1968, two Black workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, shielded themselves from torrential rain by getting inside the back of a truck, and were crushed to death by a malfunctioning garbage compactor. Their families received no insurance benefits, just one month’s pay and coverage of the funeral expenses. That tragedy immediately precipitated the Memphis sanitation workers strike.

The strike began on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, February 12. Historically, Negro History Week, which preceded Black History Month, was celebrated that week, because of both Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’s birthdays. (As an enslaved child, Douglass’s birth date had not been recorded, only the season, so he chose February 14 as his birthday.) As with the student sit-in movement of 1961, here was another key African American political action that took place in February. It is not a coincidence that Black protest coincided with a period of defiant celebration of Black history. It makes sense, because the point of the historic celebration was never simply to tell stories that had been neglected. It was also to refuse the ideology that put Black people at the bottom of every measure in American society, and to nurture their resistance.

I’m not sure what will happen with the unionization efforts at Starbucks in Memphis. But this recent episode is a meaningful reminder. Yes, Black History Month is a time to celebrate extraordinary historical figures and institutions. It is a moment to revel in culture and tradition. But it must also include political history. Black history includes the organizing endeavors of workers at chicken plants and in coal mines. It includes teachers at segregated schools who brought lawsuits against states and school districts that underpaid them. It includes sharecroppers who were fired for organizing for the right to vote. It includes steel-mill workers who were exposed to black-lung disease, and imprisoned people who were sent back to fields and treated like their enslaved ancestors. And all of that history has a direct relationship to this present political moment. Black history is, among many things, also labor history. How could it not be? After all, the conditions of Black people in the United States were most dramatically shaped by the conditions of their work. This work put inhumane demands upon their bodies, while their intellects and aspirations were diminished and denied.

Labor conditions at Starbucks are generally considered to be better than most in the U.S. food-service industry (although they have been strongly criticized for their coffee-plantation practices in Brazil, and it is worth noting that Martin Luther King Jr. was just one in a long line of African American organizers who showed explicit solidarity with poor workers internationally). I don’t know if this is a result of savvy marketing or simple truth, but I don’t think of working at Starbucks as being nearly as taxing as working at a major fast-food chain. But so what? Labor organizing isn’t just about addressing the most abhorrent conditions. It is about fairness, and whether those in corporate leadership are accountable to those who do the day-to-day work to keep the business functioning.

Currently, only around 10 percent of American wage and salary workers belong to unions, and economic inequality has been exacerbated further by the pandemic. Black History Month can give us some guidance when it comes to thinking about this dynamic. Let’s not only use it to celebrate, but also to consider its lessons for the present. We should ask ourselves: How might we consider the relations of power in our midst through the lens of Black history? And who better to guide us in that effort than the great Frederick Douglass, who with characteristic eloquence told us about the power of protest:

The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.