Nora Holt: The Most Famous Woman You've Never Heard of

A largely forgotten figure of the Harlem Renaissance and Chicago Renaissance, Holt was a Black female musician, composer, critic and free spirit, and she has a story that deserves to be told.

With the recent release of Passing, Rebecca Hall’s film version of the 1929 novella by Nella Larsen, new attention has been drawn to the Harlem Renaissance. As a fan of Larsen’s work, I’m delighted about this. And yet, I’m also reminded of how many stories of that period lie fallow. In particular, I have long been intrigued by a figure who is so obscure that even scholars of the Renaissance know little about her: Nora Holt.

Holt was an intellectual, a musician, a society lady, and a scandalous bon vivant. Admired by Gertrude Stein and Carl Van Vechten, Holt, whose big persona was fictionalized in literature, breached every contemporary rule of gender and respectability. Her financial independence and mobility allowed her unprecedented freedom as a Black woman of her era, and her talent brought her acclaim. I often think of her as the most famous unknown woman of the 20th century. But once you know about her, she’s nearly impossible to forget.

Holt was born Lena Douglas in 1885 (or thereabouts) in Kansas City, Kansas. Her father was an African Methodist Episcopal Church pastor, the Reverend C. N. Douglas. Her mother was Grace Brown Douglas. Both had migrated west from the upper South. Growing up, Nora (then Lena) studied piano and played the organ in her father’s church. Holt matriculated at Western University in Kansas and graduated as valedictorian with a degree in music in 1917. The following year, she earned a master’s degree at Chicago Musical College. Historians believe she was the first African American woman to earn a master’s in music. Her thesis was an orchestral work called “Rhapsody on Negro Themes.”

From 1917 through 1921, this classically trained composer worked as the music critic for the Chicago Defender, one of the three most influential African American newspapers in the country. Holt’s reviews were erudite and thoughtful, displaying sophisticated musical understanding and a gift for eloquent prose. She was also an advocate for musicians, and co-founded both the Chicago Music Association and the National Association of Negro Musicians.

These details alone would situate her as a leading, historically relevant example of accomplished, respectable Black bourgeois ladyhood. But as her life unfolded, a much more animated story emerged. Yes, she was a critic, but she was just as likely to stand on a table in a nightclub, body wrapped in satin, and sing a bawdy blues song. She married for the first time at 15 and would have five husbands in her lifetime. Her fourth marriage, to wealthy Chicago cabaret and speakeasy owner George Holt, ended with his death. He left her with substantial wealth and a great deal of freedom.

Lena Douglas took on the name Nora Holt after her fourth marriage. In the years following George’s death, the three faces of Nora Holt were revealed in the Black press. Follow one thread and you see a music critic. Follow another, you see an internationally famous performer. Another still reveals how often she flouted the rules of ladyhood. All three together present a fascinating woman of a sort rarely recounted in American history.

In 1923 Holt married Joseph Ray, a Black man who was secretary to steel magnate Charles Schwab. Theirs was a lavish wedding, with guests from all across the country. The Pittsburgh Courier, another successful African American newspaper, reported on the wedding, which occurred less than a year after Holt’s death. Somewhat snidely, they wrote that Nora, the “‘poor’ widow holding more stock in the great Liberty Life Insurance Company than several others of the largest directors put together will add to her possessions $10000 worth of preferred Class A securities of the United State Steel Corporation … the gift of Joseph L. Ray to his charming bride.”

This description was written under the heading “More Like ‘White Folks’ Every Day,” a caustic comment likely only legible to African American readers who, though excluded from dominant society due to racism, had their own passionate critiques of the moral and ethical behavior of white people. Liberty Life Insurance was the first African American life-insurance company in the North, and was for many Black people the only way to insure a modest inheritance after death, or at the very least the ability to cover funeral costs. But one of its new shareholders, Nora, failed the moral standards of the community that supported it.

After a honeymoon in Europe, it was anticipated that Nora would settle into Ray’s home in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and take care of his two children by a previous marriage. But she felt constrained by suburban life. Soon she was making off to big cities for the weekend, enraging Ray. This early conflict was the seed of what would become a multiyear divorce proceeding that was covered in great and sensationalistic detail in the Black press.

In June of 1924, The Pittsburgh Courier announced that the Ray marriage “has wrecked ’mid turbulent waters.” Nora had left Bethlehem and settled “with her elaborate wardrobe and jewels” into the home of Carolyn Wilkins in Harlem. According to gossip, Nora had asked Ray to set her up with an apartment in Harlem, and he had refused. By July she returned to Bethlehem. But that reunion was short-lived.

That fall, Ray began to have Nora followed by private investigators.

In January of 1926, The Pittsburgh Courier reported that Nora had been found with attorney William L. Patterson in a Harlem rooming house. The paper reported that “the room had apparently been engaged only for the night, as Mrs. Ray had only a small bag containing silk negligees and other personal effects.” Though the reporting was salacious, it wasn’t exactly a secret that Patterson and Holt had been carrying on. The paper had reported that they attended an Urban League charity fundraiser together the previous November.

Finally, after refusing comment through all of this salacious reporting, Nora agreed to speak to the press in February of 1926. She told a reporter for the Chicago Defender that “the latest developments in the domestic affairs of Mr. Ray and myself as reported and commented upon by some of the newspapers and periodicals forces me to make a public statement denouncing the unfair manner in which they have been publicized and commercialized the whole proceedings.” She accused Ray of attempting to blackmail and vilify her. She concluded the statement by saying, “I have been unjustly framed and persecuted not because of any crime, but to appease the anger of an unscrupulous husband whose sense of decency should have restrained him from playing the game of Ray versus Ray in such an unmanly and unsportsman like manner.”

Nora departed for France that May, leaving the gossip, and her estranged husband, behind. She did a three-month stint at a café in Paris as a performer, before entering a six-month engagement at a resort in Monte Carlo. She was wildly popular, receiving accolades abroad that were excitedly reported in the African American press. In fact, she was about to take on a leading role as an actress in a stage play, but was called back to the states for her divorce proceedings in March of 1927.

In the court proceedings, Ray accused Holt of bigamy, saying she wasn’t actually divorced from her previous husband, Bruce K. Jones, when she married him, and therefore the Ray marriage was void. He also accused Nora of stealing $12,000 worth of jewelry from him prior to their engagement.

Holt argued that she was indeed divorced from Jones, and that the divorce had been completed before she married George Holt.

Over the next several years the couple were in and out of court. Holt consistently prevailed against Ray’s charges. They both had prominent attorneys: Ray’s were most often Black, while Holt hired a white law firm to represent her.

The press ate up her private life but also her audaciousness, especially in 1929, when she changed her hair color from auburn to blond. Bold for any woman, alarming for a Black woman. But that golden hair against honey-brown skin also served her in her career as a performer.

In 1929, Holt appeared in London at the popular Café de Paris in Coventry. She was then residing in Mayfair, and it was reported by the Daily Sketch that she was a “most attractive” American woman who wore beautiful Parisian gowns. London’s Daily Express described her as a particular “type”: “Creole femininity has often exercised a strange fascination over the most iron-willed of men. The most celebrated of them all was no less a woman than Napoleon’s Josephine … Something of this attraction may be felt in the singing of Miss Nora Holt, a blond Creole whose first London appearance I witnessed.” The writer exoticized her beauty. Yet he also remarked on her voice: “It can produce sounds not comparable with orthodox singing at all or indeed any human utterance. They range from the deepest bass to the shrillest piping, and are often unaccompanied by words.”

In London her performances were frequented by the Prince of Wales. On one occasion she sang for Lady Carisbrooke and her guests, who included ambassadors from France, Italy, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria, along with other aristocrats. For that performance, Holt was gifted with an amber and jade bracelet. In exchange, she gave the lady a gold cigarette case.

The Black press continued its gleeful reporting. At a time when the majority of Black American women did menial work and lived in poverty, Holt traveled in ermine, wore her hair in tousled blond curls, and presented the picture of a global cosmopolite who could cross all Jim Crow barriers with charm and elegance.

In December of 1929, Holt was called back to the States to finally settle the divorce.

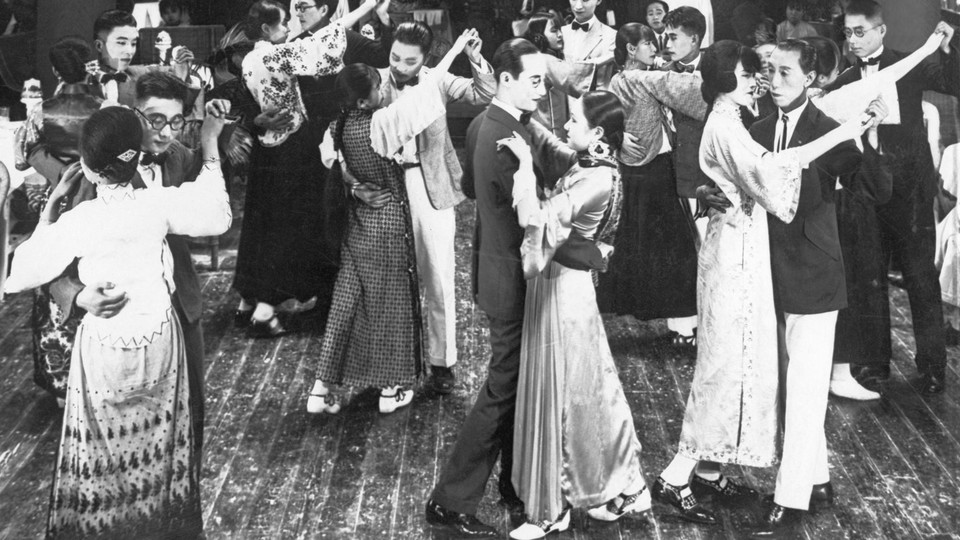

It is then that, to me, she entered the most unexpected part of her life. In the early years of the Depression, Holt traveled to Asia. She sang in Singapore, Tokyo, Bombay, and, for the longest period, in Shanghai. Nora worked as the hostess at the Little Club, an establishment that was part of Shanghai’s celebrated nightlife zone. She learned to speak Chinese, and was, yet again, celebrated for singing the blues and other Black American fare. And it appears that she weathered the early years of the Great Depression without the economic hardship that most of the world experienced.

Although the Harlem or “New Negro” Renaissance largely petered out due to the Depression, plenty of writers and artists continued to work under the far more trying circumstances. A number of scholars have therefore argued that the timeline for the Renaissance perhaps ought to be extended beyond the standard end point of 1929. Similarly, because so many of the writers and artists worked and hailed from other regions, scholars have argued it shouldn’t be referred to as the “Harlem Renaissance.” Certainly, Chicago was a more robust stage for African American musical developments, and arguably music was even more important than the literature we tend to focus on from that period. Over the course of her life, Holt was at the center of the Black music scene in Chicago, Harlem, Europe, Asia, and Los Angeles.

In a 1932 interview, the prominent Black novelist Wallace Thurman, who was also from the Midwest, shared some of his preferences and dislikes. He said he hated Negro-uplift societies, Negro novelists (including himself), divorce laws, politics, and policemen. He liked Shelley, Keats, Frederick Douglass, and russet-brown-skinned women with beauty marks on their shoulders. His philosophy was hedonism. Finally, he said that he would like to fall in love with a woman like Nora Holt. That Wallace is thought to have been a gay man is only minimally consequential to the point I’m making. He was sending a message to the public by admiring Nora Holt. He proved himself to be a free spirit.

In the same year, an article in The Pittsburgh Courier sounded a moral panic about a drag ball that Nora attended: “Queer people, both men and women, who, it is claimed do not love or feel like ordinary men and women are increasing. They are said to have their own circle, their many rendezvous and certain hotels and private places cater to them. An intricate social system built up outside society is said to be dominated by them.” The author went on to comment on the absence of a color line in such gatherings. “Complexions varied from the chalky pale white of a Caucasian dope fiend … to pure deep blackness of a native African. Browns, taupes, high yellows and reds were to be seen, and whites were in profusion … There are all types of the individual, rich and poor great and small and many of them are highly distinguished writers, artists, sculptors, painters, novelists and accomplished folk of no mean ability.”

Critics have long noted that queer communities were at the center of the Renaissance, so this article is unsurprising. What intrigues me, however, is how Nora is placed in the center of the action. She was a transgressor. But she was also a person who valued the rigors of formal study. She was both gracious and outlandish. Perhaps this isn’t a notable combination of qualities today. But it is unusual in terms of how we categorize historic figures.

In 1933, Nora returned to China. She came back to the States in April of 1934 on the Asama Maru ocean liner. Of her journey, she said, “I am dropping into Hollywood, looking the situation over and at the same time overlooking it for the moment for I am on my way to Chicago and then the inevitable Harlem.” By December she was in Chicago. I do wonder what Holt made of the desperate, Depression-era conditions on the South Side as she attended a set of swanky parties, before taking off for Los Angeles and then going back to Shanghai. I must admit being somewhat disturbed that she seemed largely disengaged from the devastating historic moment, but also fascinated by her lack of piety when it came to nearly everything, including modesty.

Los Angeles became her home base, even as she traveled through the 1930s. She returned to the formal study of music at the University of Southern California, and became a certified night-school teacher. Nora also opened a beauty salon, and occasionally performed. In the summer of 1935, Holt had a show at the Walroys Gallery, in Los Angeles. It was reported that she “sang a repertoire of songs, accompanying herself on the Steinway, ranging from early American folk lore to those Frenchie ditties for which she is so famous the world over.”

That same year, Holt also worked with writer Langston Hughes and composer Thelma Brown to write “Ethiopia Marches On,” an anthem in support of Ethiopia’s war against Italian colonial forces. It included the lyrics “Enemy GO! and come no more. Abyssinia, let the war drums roll! Ethiopia, homeland of my soul! I’m going to stand by you til every foe is gone—Abyssinia march on and on.”

I take this song as an indication of a political consciousness that isn’t immediately apparent in the news stories about her. There are moments here and there, of course, when her name is listed as part of fundraisers, or civil-rights committees. But it is muted.

For her politics to fully emerge, I imagine, we’d have to have more of her first-person reflections. As noted by the late great literary critic Cheryl Wall in her essay “Nora Holt: New Negro Composer and Jazz Age Goddess,” depictions of Holt tended to be sensational even when shared by her friends. But there was clearly much more to her.

As a critic and not a memoirist, Holt left behind few first-person accounts that one can use to sketch her life. But the absence of her compositions is an even greater obstacle to properly situating her in history. Holt’s 200-odd works of orchestral music and chamber sounds were stolen from her storage space in the late 1920s. Only one published work, “Negro Dance,” remains. Her sound is out of reach, despite the fact that it resonated around the world.

I hold onto a lingering hope that Nora’s work is in someone’s attic, waiting to be discovered. She lived until 1974, and continued to write about music and ultimately hosted a radio show. Yet she’s elusive. I’ve lamented that we could say so much more about her, if only we had those lost pages. But one thing I learned writing a biography of Lorraine Hansberry and about the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” is that, sometimes, the evidence you want only appears once you tell people you’re looking for it.

So I’m here, telling you that I—along with others like musicologist and pianist Samantha Ege, who has beautifully rendered Holt’s one extant piece of music, “Negro Dance”—are looking for Nora Holt. Even with the incomplete picture we have, she offers a vision of a woman outside of all the predetermined boxes, imperfect, lustful for life, and unapologetically brilliant. Chin up, even while being dragged through the mud. Nora Holt was her own muse and composer of her own life.

Samanthe Ege performing “Negro Dance”