The No. 2 book on the New York Times nonfiction list is a searing personal reflection by a former Republican strategist named Tim Miller. It’s called Why We Did It: A Travelogue From the Republican Road to Hell, and it’s one part searing personal reflection and one part social commentary. Tim explores why and how the Republican Party came to embrace not just Donald Trump but the entire toxic traveling circus that is the MAGA movement.

I read Tim’s book with intense interest in part because he’s so different from me—he’s a gay married man living in California; I’m a conservative Evangelical living in Tennessee—but also because he came from a very different part of the conservative movement. He was a political operative. I was an ideological conservative. He entered politics through the consultant class. My part of the movement seemed more pure. Allegedly we were the ones with the genuine beliefs.

Yet the overwhelming majority of both wings of the movement fell in line behind Trump, defended the indefensible, and defend it still. Why?

The genius of Tim’s book (and I highly recommend reading it) is that it cuts through the rationalizations—and the rationalizations are endless—and gets ultimately to a heart-level question: Who are you, really? Or, put another way, What is your core identity?

I don’t think those who live outside the American right understand the extent to which the upheaval of the Trump years impacted multiple, intersecting aspects of personal identity and exposed the true hierarchy of personal values.

Let’s take the example of Lindsey Graham. Yesterday in The Atlantic Mark Leibovich published a scorching profile of Graham, Kevin McCarthy, and other politicians who’ve been particularly sycophantic to Donald Trump. Leibovich highlights this revealing exchange:

Once, early in 2019, I asked Graham a version of the question that so many of his judgy old Washington friends had been asking him. How could he swing from being one of Trump’s most merciless critics in 2016 to such a sycophant thereafter? I didn’t use those exact words, but Graham got the idea. “Well, okay, from my point of view, if you know anything about me, it’d be odd not to do this,” he told me. “‘This,’” Graham specified, “is to try to be relevant.” Relevance: It casts one hell of a spell.

Ask any person to describe themselves, and they’ll likely respond with a mix of characteristics and virtues. They’ll describe their profession (lawyer, banker, plumber), their relationships (husband, father, grandfather), and their politics (Republican, Democrat), and if asked they might even describe their perceived virtues (honesty, fidelity, fortitude).

But what if the virtues conflict with other core parts of a person’s identity? Prior to the Trump years, Graham was joined at the hip with the maverick John McCain. During the 2016 campaign, he called out Trump’s flaws early and often.

So how would one describe Lindsey Graham, before Trump? He was a senator. He was powerful. And while all politicians are flawed, I’d say he was generally perceived to be both honest and independent.

But then, during the Trump years, honesty and independence directly and starkly clashed with status. Time and again, men and women in America’s political class found that they couldn’t possess both virtue and power. They had to make a choice.

The writer and Christian theologian C. S. Lewis wrote, “Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality.” Another way of putting it is that we don’t really know if we possess a virtue until it is tested.

We might think of ourselves as honest, but we don’t really know if we are until honesty carries a cost. Or we might think of ourselves as physically brave, but we don’t know if we are until we face a mortal threat. We might be sure that we’re faithful, right until the moment when temptation is at its peak.

During the Trump years, the collision between status and virtue was constant and relentless. Trump never gave anyone a breather. He was never chagrined or mollified by scandal. He never apologized. He never turned over a new leaf. He just charged from one lie to another, and his demands for absolute loyalty left his defenders and followers with little ability to separate themselves from his worst moments while still remaining in the Republican tent.

As we’ve seen from days of courageous testimony before the January 6 House Select Committee, it is quite possible to say “I’m a Republican, and I’m honest.” But with each passing week—and with each new revelation—it grows more difficult to say “I’m a Trump Republican, and I’m honest.” Status conflicts with virtue, and status wins.

And don’t think for a moment that this is a uniquely Republican or right-wing tension. In an extremely polarized nation that is full of angry, tribalized politics, it is the exception rather than the rule to see people have the courage to call out the excesses of their own side. To do so can raise risks to your reputation, your friendships, your livelihood, and sometimes even your life.

Tim Miller’s book is a poignant, updated version of a tale as old as humanity. His self-reflection and sense of personal sorrow is important. He’s not just scolding others; he’s repenting of his own sins. Coming from a very different wing of the conservative movement, I share many of his regrets.

In fact, when I look back on my life before Trump came down the escalator to announce his run for president, I’m embarrassed at how easily I integrated my ideals and ambitions. I didn’t see a conflict between my partisanship and my virtue. Indeed, I viewed my partisanship as part of my virtue. It is painful to discover the contradiction.

So it’s one thing to state the timeless truth that when men and women face a conflict between their status and their conscience, they’ll find a way to choose their status. They’ll be like Lindsey Graham and choose relevance. It’s another thing to find that impulse in yourself. We all have to answer that key question, Who are you?

And when you choose status that answer can be compelling: a senior senator in the case of Lindsey Graham, or a future speaker of the House for Kevin McCarthy, or in other contexts it can be a party chair or a Fox News contributor. There are jobs available that people spend a lifetime dreaming about and striving to obtain.

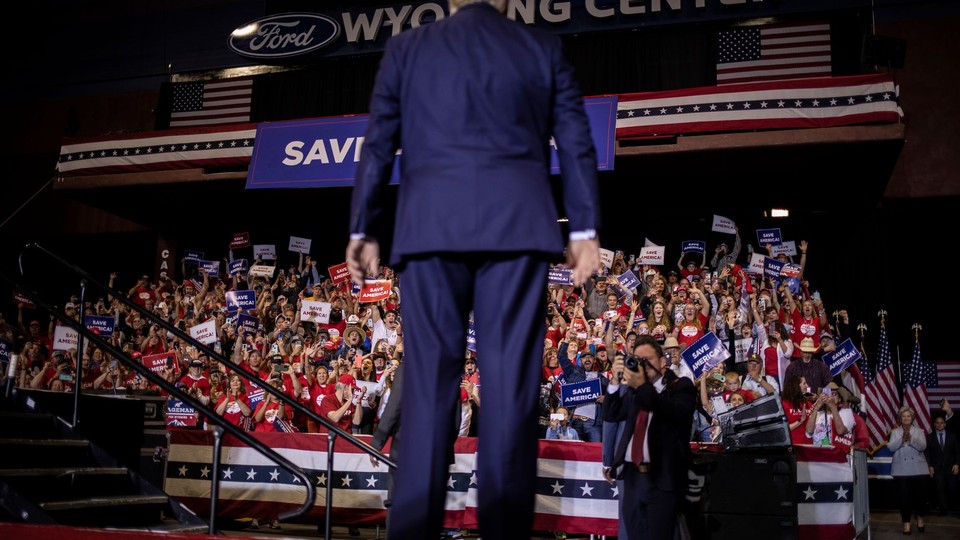

But the more one ties themselves to MAGA America, the more that answer cannot include other descriptions, such as an honest man or a brave woman. As Miller documents in painful depth, an entire segment of America’s political class has faced the direct collision between virtue and power, and for all too many, the love of power clearly prevailed.