I Am in Cloud-Storage Hell

Services such as iCloud and Google Photos are holding my memories hostage.

Listen to more stories on the Noa app.

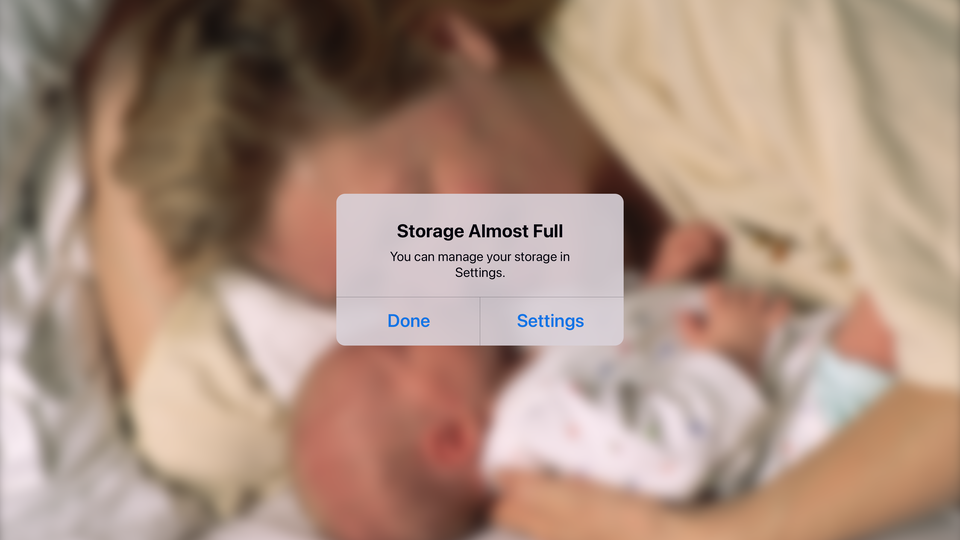

Here I was, going about my day and minding my own business, when a notification popped up on my phone that made my blood run cold: Your iCloud storage is full.

I am, as I’ve written before, a digital hoarder whose trinkets, tchotchkes, and stacks of yellowing newspapers (read: old pixelated memes) are distributed across an unknown number of cloud servers around the globe. On Apple’s, I’ve managed to blow through 200 gigabytes of storage, an amount of data that, not even a decade ago, felt almost infinite: my own little Library of Congress, or that warehouse from the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, filled with screenshots of bad tweets. The overwhelming majority of this space is dedicated to 31,013 photos and 1,742 videos I’ve personally taken. The rest is likely brain-cell-destroying junk that others have sent me in texts and group chats.

Running out of iCloud storage is obviously not an unusual circumstance. But I have also recently been forced to upgrade my Google storage from 100 to 200 GB. I started using Google Photos when it was introduced, in 2015, and I loved the convenience—but now I’m paying for duplicate services, terrified that I might wipe out precious memories if I cancel one. I’m already watching the status bar creep toward the next unthinkable milestone: $9.99 a month for two terabytes of storage. And it wasn’t until writing this story that I realized I’m paying a nominal monthly fee for a Dropbox account that hosts a few gigs’ worth of work files for a job I haven’t held since 2018. This is to say nothing of the multiple pre-cloud hard drives I have floating around in a cardboard box somewhere in meatspace.

My online life is a sprawling, overwhelming mess with a price tag that increases every few years. If these archives were in my home and not in the cloud, I have to imagine that visitors would pull me aside for an intervention or refuse to come over altogether. It seems I’ve reached a tipping point, where the digital detritus of my personal life has exceeded the once-unimaginable boundaries of online storage. It feels quaint now, but there was a feeling of freedom that came with those first gigabytes of cloud storage; in 2007, it seemed like I would never fill the 2.8 gigabytes that Gmail offered.

I’ve lived decades of my life online, and I now feel like I’m bumping into the walls of the internet. These days, it’s not uncommon for me to sign up for a new app or service, only to realize that some previous version of myself created an account years ago. My inbox—also a disorganized hellscape—is full of pesky emails from services I haven’t used in at least half a decade. Like ashes from a campfire, my digital self has been thrown to the wind and scattered across the internet. This feels untenable.

You, too, might be butting up against an internet that no longer feels boundless. Where do we go from here? There’s a cyclical nature to data glut: Tech companies keep providing us with wonderful, useful communication and documentation tools, which we then use to generate a lot of data, and which tech companies then offer convenient subscription tiers to support. Because the media we create through these services tend to be intensely personal or sentimental, we are unwilling to part with or cull our archives; it’s not like they’re taking up valuable space in the garage.

And unlike the physical photo albums that you may have lingering in your attic, these digital media have been imbued with interactive qualities; Apple and Google are now in the business of repackaging your photos into thematic slideshows set to music. These “memories,” which is what the tech companies are calling them, are yet another technological solution to a problem these same companies have introduced. Memories are a modest feature, but the implications of outsourcing bits of our memories to Big Tech are considerable.

As I wrote in 2022, when I store information for later, I’m often confusing that right-click/save-as process with the actual work of remembering something important. I can imagine an exaggerated future version of this process: A family member dies, and iCloud offers up its own version of a memorial service, pulled from terabytes of personal information. Siri, who was Grandpa? *manipulative cello music begins to play* I’m not thrilled at the idea of Google getting a first crack at my eulogy, but there’s also something potentially comforting about a world where those who want to can leave behind exhaustive documentation of their life.

At its core, my unease comes from the inescapable notion that the internet has imposed its vertiginous scale on some of the most personal elements of my life. Whether they are old accounts or bad, cringey passwords, pieces of me lurk in databases that I’ve forgotten exist, their owners processing and refining the information like it’s a natural resource. Perhaps it is a gift that these products allow us to relive and reflect on moments that would otherwise pass us by. But there is also a beauty in endings and in the ephemeral.

Public figures belong in the history books, but do the rest of us? I’ve long loved the web because, like space, its boundlessness evokes both excitement and possibility. But as the internet gets bigger and more unknowable, and as my own presence across it continues to grow, I feel that the opposite is happening to me—that I am becoming hyper-knowable, paying multibillion-dollar companies so that I may curate my own self-indulgent presidential library whose final purpose is unclear. An internet that once felt limitless and freeing now feels like a constraint.