‘Evidence Maximalism’ Is How the Internet Argues Now

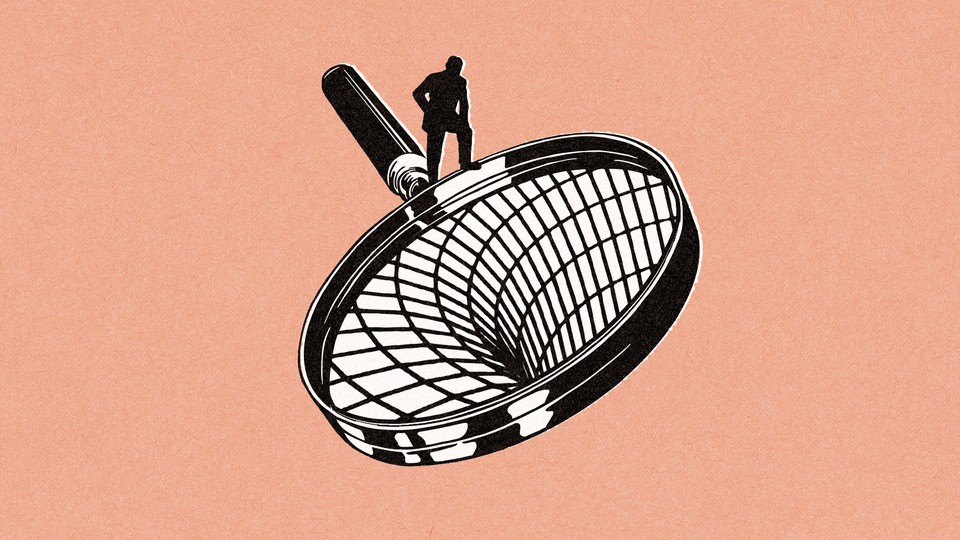

A simple theory for why the internet is so conspiratorial

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

On Friday afternoon, news broke that the beloved actor Carl Weathers had died peacefully in his sleep at the age of 76. No cause of death was announced. Within hours, anti-vaxxers offered an unsolicited explanation for his passing: They pointed to a tweet, posted by Weathers in 2022, in which the actor noted that he was “vaxxed and boosted.” Weathers became the latest celebrity to have their death co-opted by the #DiedSuddenly conspiracy theory, in which vaccine skeptics insinuate that people are dropping dead after receiving a COVID vaccine. Four days later, the same cycle repeated itself following the death of the country-music artist Toby Keith. For these anti-vaxxers, celebrity deaths are never random or senseless. Each one is a piece of evidence that is instantly compiled to explain and sustain a particular, dangerous worldview.

Conspiracy theorists and propagandists have always tried to spin current events. But on the internet, it has become unnervingly common to encounter brazen conspiratorial ideas. As my colleague Kaitlyn Tiffany wrote last year, #DiedSuddenly has thrived on social media, especially X. These days, some headlines can sound as if they’re describing events occurring in a parallel American timeline. An airplane experiencing a serious mechanical failure becomes “Yes, DEI Will Make More Planes Fall out of the Sky.” The most famous pop star in the world dating one of the NFL’s best players turns into a shadowy “deep state” plot: “Right-Wingers Say Super Bowl Is Rigged So Taylor Swift Can Endorse Biden.” Online, no event can stand alone. It is immediately thrust into a sweeping narrative.

Mike Caulfield, a researcher at the University of Washington who studies media literacy and misinformation, told me that this is the reason it feels like political discourse online has grown so unhinged, and will only become more bizarre as we press forward into the abyss of an upcoming presidential election. He has written that all of the information online—news, research, historical documents, opinions—has conditioned people to treat everything as evidence that directly supports their ideological positions on any subject. He calls it the era of “evidence maximalism.” It’s how we argue online now, and why it’s harder than ever to build a shared reality.

Caulfield has three rules for evidence maximalism. The first is that “any small thing can be evidence of my thing,” he told me. This looks like classic conspiracy theorizing—connecting dots that aren’t there. Caulfield pointed me to a recent post from an X account that claims to publish “Unfiltered Unbiased Verified 24x7 Breaking News.” The account, which has 1.2 million followers, shared a link to a TikTok video showing that Costco had recently restocked its emergency food kits. “WHAT DOES COSTCO KNOW?” the X post read. (It has since been deleted.) The implication was that another pandemic-style disaster could be on the horizon and that powerful people know more than they’re letting on.

The second rule of evidence maximalism is that “any big thing is always evidence of my big thing,” he said. Last month, when Sports Illustrated announced plans to lay off most of its staff, some right-wing influencers immediately blamed the company’s financial crisis on the magazine’s decision to feature Kim Petras, a transgender pop star, in its swimsuit issue. Like the Boeing-plane story, this “Go woke, go broke” explanation has become a common trope on the right. Instead of attempting to look for real, nuanced reasons that media companies such as Sports Illustrated are failing, it is far easier to pigeonhole the news into a narrative that fits a broader political point.

Caulfield’s final rule might be the most important: “All your evidence against my thing is, on closer inspection, very strong evidence for my thing.” A prominent example of this is the January 6 insurrection, which some on the right reframed as proof that the 2020 election was stolen. Violent footage of MAGA insurgents and militants was spun as a deep-state plot. The real rioters, they argued, were federal agents.

Of course, this kind of confirmation bias is not new, but the internet has supercharged it. Because our attention is so fragmented online, any big story—such as the Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce romance—becomes an ideological battleground, with different camps trying to ride its coattails. It’s difficult to get anyone to care about anything, including DEI programs at Fortune 500 companies, for an extended period of time, but when a plane’s door rips off mid-flight, it provides an opening. From there, any motivated actor can reverse engineer evidence with some light Googling. A Boeing plane has mechanical trouble; head to the company’s website, browse its press releases, find a DEI report that states the company is looking to “increase the Black representation rate,” and draw a causal link.

Maximalists exist across the political spectrum, and the stakes of the upcoming election will only embolden them. There is an obvious asymmetry, though: The far right has built a politics around evidence maximalism, which is likely to continue in 2024. Donald Trump’s campaign, which has constructed an entire alternate universe in which the 2020 election was stolen, may suddenly find evidence of new fraud everywhere in the coming months to claim that Democrats are trying to steal a second election. Everything is fair game, which is how Swift’s relationship somehow became a liberal plot to endorse Joe Biden at the Super Bowl. The far right offers a cautionary tale of what comes from dismissing any uncomfortable information in favor of making connections out of nothing. Adherents to MAGA orthodoxy have built a world in which they’ve alienated themselves from popular institutions and elements of American life, where they must boycott Target, Bud Light, and Disney.

It’s not clear whether there’s an easy fix for any of this. But there are ways to navigate the morass of information, Caulfield argues. When you see a news story or a post online, it’s worth asking questions that force you to consider whether the story is actually as important as its framing suggests. He offered a few questions readers can ask themselves. In the case of a story about mail theft, you could immediately pin the blame on dirty political tricksters, or you could ask yourself, Could this be evidence of something smaller and more local, such as petty criminals trying to steal checks? “Sometimes the thing in front of you is the strongest evidence for your biggest issue,” Caulfield told me. “But most of the time, it’s not.”

Such awareness, especially in a grueling election year, is crucial, because evidence maximalism doesn’t just poison discourse or make for weird headlines; it leaches humanity out of the way people see the world. Too often, evidence maximalists take the misfortunes, successes, and stories of other humans and turn them into exhibits presented to an imaginary jury to win a trial that can’t be won. A mass shooting becomes a political cudgel; a tragic death turns into a way to question science; a bunch of teens on TikTok becomes a stand-in for “the radical left.” What is at stake is an information ecosystem where there is less and less focus on what is happening to people, because the story itself is meaningless outside of a way to score political points. An environment governed by the laws of evidence maximalism is a cold, nihilistic one. When everything is evidence, nothing is.