Superman Is Still America’s Greatest Superhero

We need Christopher Reeve now more than ever.

Updated at 1o:00 p.m. ET on October 8, 2022

[Warning: This article contains spoilers for the 1978 movie Superman.]

As I’ve told Peacefield readers, I’m now the lead writer on the Daily, so please sign up for more of my writing on politics and international affairs. Today, however, I want to talk about that strange visitor from another planet with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. He was born as Kal-El and lives among us as Clark Kent, but we all know him as Superman.

I realize that we’re now living in a world of entertainment populated by superheroes who are troubled and moody (such as director Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight masterpieces about Batman), or troubled and moody, but very funny (which pretty much sums up most of the Marvel Comics Universe, the “MCU” that has dominated box offices for years). And in fairness, I love a lot of that stuff; I think Deadpool, for example, is a subversively hilarious take on the genre.

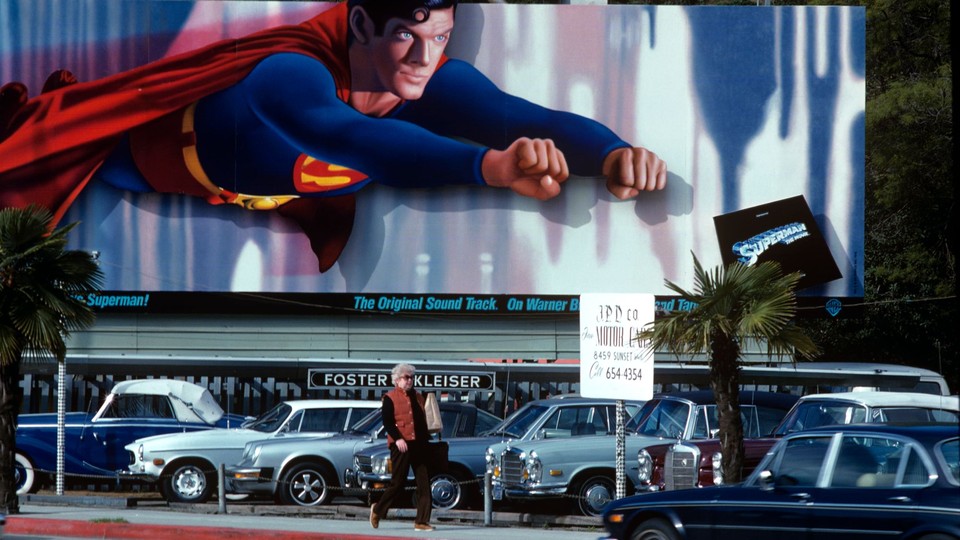

But the 1978 Superman—sometimes called Superman: The Movie—is still the greatest superhero movie, and its star, the late Christopher Reeve, the greatest Superman. And if ever there was a time America needed him, it’s now.

Before we get to what makes Superman worth such praise and why you should watch it—especially if you haven’t already—let’s talk about the character.

One of the chief criticisms leveled against Superman is that he is, in every way, boring. Flung to Earth from a dying planet, the Last Son of Krypton lands in Kansas, where is adopted by farmers and grows up to be a great kid. He’s always doing the right thing, staring wistfully at the American flag, and being nice to his folks. In later years, DC Comics tried to tone down the mom-and-apple-pie stuff by having Superman declare himself a “citizen of the world,” but they weren’t fooling anyone. He’s always going to be the Big Blue Boy Scout.

And sure, his invulnerability is a problem. Even I winced at a moment in one of the comic books I read as a kid when Superman literally pushes the Earth out of the way of some approaching danger in space. It’s difficult to create dramatic tension over a guy who can only be harmed by radioactive chunks of his home planet (and, apparently, by magic).

Both his hometown roots and his immense abilities, however, are part of Superman’s appeal—or they would be, in a less cynical time. I mean, come on: a powerful man who grows up in a small town, never forgets his roots, always honors his parents, and adheres to the values instilled in him as a boy in a loving community? How do you not admire the guy?

Superman isn’t some Asgardian party boy, or a demented sociopath driven to dress like a bat, or a freak who becomes an instrument of chaos if he loses his temper. He’s not even an alien, really; he doesn’t know anything about his origins until he reaches his teen years. The Superman canon, instead, follows the standard mythic-hero story line of an adopted son, unaware of his true powers, who enters adulthood and must become a savior. Think King Arthur, Hercules, and, well, Jesus. (Granted, some of the movies, in particular the 2006 misfire Superman Returns, hit that Christ imagery a little too hard—which is a bit odd given that Superman’s creators, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were Jewish kids who met in Ohio.)

More important, Superman embraces his power as both his destiny and his duty, rather than becoming a threat to humankind. Some writers have wondered about this alternate path for the Man of Steel, including the 2019 movie Brightburn, in which an alien superboy’s adoptive Earth parents realize—too late—that the foundling they’ve taken in is a bad seed, and he’s going to kill everyone. As in, everyone. And, in a novel and later film both titled Superman: Red Son, DC Comics experimented with an even more intriguing scenario: What if baby Kal-El’s spaceship landed in Soviet Ukraine in 1938 instead of Kansas? (Suffice to say that “Soviet Superman” gets weird.)

No one has imagined Bad Superman better, however, than the Amazon Prime series The Boys, which posits a world full of enhanced meta-humans led by a Superman stand-in named Homelander, who’s a complete psycho. I’ll write again about The Boys another time, but the beauty of the Superman character is that he isn’t Homelander. He knows he could subjugate the entire world, and yet he doesn’t.

Superman, who is as corny as Kansas in August, is a study in what happens when ultimate power is constrained by self-discipline and virtue. In the 1978 movie, a young Clark Kent complains to his father about hiding his powers, and about how, if he went out for the football team, he could win every single time. His father, played by Glenn Ford, reassures him that there is more to life: “You are here for a reason. I don’t know whose reason, or whatever the reason is … But I do know one thing. It’s not to score touchdowns.”

It’s a wonderful moment, in which a father gently guides a teenager toward wisdom and responsibility. Imagine if any of us woke up and found that we were able to fly, that we were invulnerable even to nuclear blasts, that we could laser anything we don’t like into ashes by just staring real hard. Would we have the foundation of character, of patriotism, of self-control to use our gifts in the service of our country and the human race? Or would we end up like Homelander, a sadistic, insecure (and very dangerous) bully whose credo is “I can do whatever I want”?

Superman can do whatever he wants, too, but he doesn’t. He was raised better than that.

Moving on from the Superman character, let’s talk about the 1978 film itself. If you like superhero movies, you can thank Superman; it was the first serious, big-budget superhero movie of the kind we’ve come to know today. How serious? How about Oscar-winner Marlon Brando as Superman’s father, Jor-El? Gene Hackman—like Brando, one of the greatest actors of our time—played the heavy, Lex Luthor. Ned Beatty, another Oscar winner, played a supporting role as Luthor’s goon.

You want more serious? The screenplay was by Mario Puzo, the guy who wrote The Godfather. That’s serious.

The producers didn’t skimp on locations or special effects, either. The posters in front of theaters said, “You’ll believe a man can fly,” and using a number of tricks, including literally dangling the actors from wires, the effects still hold up today. (I would say, in some cases, they’re even better than the CGI festivals that pass for effects now.) I was 17 when I saw Superman in a theater with a pal, both of us thinking we were in for a campy experience like the 1966 Batman movie. When Reeve takes to flight for the first time in the picture, we both just let out a “Whoa,” and realized we were watching something better than a Saturday-matinee science-fiction flick.

And if you’re going to make a splashy epic in 1978, there’s only one choice of composer. The score for Superman is by John Williams, and I would argue it’s one of his greatest film works, even in an oeuvre of astonishing scores including Star Wars, Jurassic Park, and Schindler’s List, among others. For Superman, Williams created something very American, melding a majestic and triumphal heroic theme to something like a John Philip Sousa march. The music was nominated for an Oscar and nabbed a Grammy for Best Instrumental Composition.

The whole thing might have been a disaster, however, without Christopher Reeve. The producers thought of casting Hollywood A-listers, which would have resulted in the unintentionally hathotic spectacle of seeing well-known actors such as Clint Eastwood or Robert Redford in tights and a cape with black hair dye. I suspect there would not have been enough popcorn to keep up with what we would have all thrown at the screen.

Instead, they cast an unknown actor in his late 20s who, as you can see in the screen tests, is somewhat scrawny before he bulked up for the job. Tall and gawky as Kent, muscular and assured as Superman, he sold the role and nearly became typecast. Indeed, Reeve caused a kind of reverse typecasting: We could see him in other roles, but we could see no one else as Superman.

Reeve’s ability to play the Kansas farm boy who becomes a demigod was essential to the success of the movie, because the script itself wasn’t especially memorable. Its most important line had been taken from the Superman TV series, a stuffy 1950s relic that starred a 40ish actor with a dad-bod in the title role, and it could have been a complete howler if Reeve hadn’t been able to pull it off. Instead, Reeve made it all seem effortless. When his love interest, Lois Lane, asks Superman why he’s here, he answers with deadpan seriousness: “To fight for truth, justice, and the American Way.”

Readers younger than a certain age will probably roll their eyes at that kind of schmaltz, but the 1978 Superman meant it. This was before everything in modern movies was required to be drenched in postmodern irony and cynicism. There were no layers of character here, no double meanings, no sly wink at the camera to indicate that everyone in the production was too hip to ever say something as lame as “the American Way” and mean it.

When Superman saves Lois at the end of the film’s first act, it’s also his debut in public in his famous costume. A pimp in late-1970s Huggy Bear getup gives him an appreciative shout, and Superman says “Excuse me” before flying off. He then catches Lois, falling from the top of a skyscraper, high in midair. “Don’t worry, miss, I’ve got you.” (“Excuse me?” “Miss?” Where’s this guy from, Kans—oh, right.) A wide-eyed Lois (played by Margot Kidder) looks down and says: “You’ve got me? Who’s got you?!”

And instead of smirking, or hauling off a one-liner, or deeply intoning, “Well, I’m Superman,” Reeve merely smiles politely and chuckles. Then he catches a falling helicopter with one hand.

This is one of the best scenes in the film, not only for its effects but for the understated confidence with which Reeve took to the air. When asked his name, he says only: “A friend.” He then heads out for a night of foiling robbers, helping cops, and yes, even saving a kitten in a tree.

Hackman’s Luthor is, for those of us who have had to endure the era of Donald Trump, practically a celluloid version of what Trump could have become if he weren’t so self-defeatingly ignorant and incompetent. Let’s go down the list: Luthor is an insufferable, sadistic narcissist who lives in a garish lair on (well, under) Park Avenue. He has a snippy trophy girlfriend. His top aide is a cultishly adoring moron. He hates his father, he’s fascinated with nuclear weapons, and his big plan is all about destroying California so he can cash in on his one true obsession—real estate.

Too on the nose, really.

Reeve’s Superman is determined to stop all this, of course, and after thwarting Luthor’s plan to kill him (with some help from Luthor’s girlfriend, who naturally has a crush on our hero), he saves Lois and all of California by making the Earth revolve backwards and turning back time. Okay, it’s a bit much, but at least he has to overcome the ghost of his birth father warning him not to do it. He delivers Luthor and his minion to prison—oh, if only art could inspire life—and the warden thanks him for making the country safer. “No sir — don't thank me, Warden,” Superman says, with slightly awkward self-deprecation. “We’re all part of the same team. G'night!” He then flies off into a sunrise over the planet, with a big smile. He then flies off into a sunrise over the planet, with a big smile. No matter how bad things get, he’ll be there.

Whether we realize it or not, this is what we need right now. You can keep your antiheroes, your New York hipsters cracking wise with gods and presidents, your disturbed and conflicted brainiacs, and your waiflike, self-pitying meta-humans. We’re in free fall, and we need someone to catch us and then smile at our naivete when we ask, in astonishment, how such a thing is even possible. We need to look at someone who holds the power of life and death in his hands and know that when he says he’s a friend—to you, to America, to all of humankind—he’s not just putting us on. Is it too much to ask?

At the end of the sequel (much of which was filmed at the same time as the original), Superman flies to the White House, which has been trashed by bad guys. He looks at the American flag he happens to have brought with him and, with pure patriotic warmth, says: “I’m sorry I was away so long, Mr. President. I won’t let you down again.”

Indeed, it’s been way too long. We need a hero who can be an example to a damaged country. Christopher Reeve, we need you—and America needs Superman.

P.S. Before I leave this subject, I think we can all agree on one thing: that my Atlantic colleague David French is completely wrong in his admiration of Aquaman, among the lamest superheroes of all time. The guy’s power is swimming fast and talking to fish, for crying out loud. David, I implore you: Watch The Boys and realize why the creepiest, ickiest, weakest parody character in that series is The Deep, based on Aquaman. Go north, David, to the Arctic, and join us at the Fortress of Solitude for some deprogramming.

This article was updated to correct the quote from the ending of the 1978 Superman film.