For the holiday weekend, I thought I would take a break from politics and war, especially since I'm writing on both over at The Atlantic’s Daily newsletter (which you can find here), and instead talk about something a bit more pleasant and nostalgic.

I am a night owl. (One might say insomniac, but I do sleep, if on something of an odd schedule.) Once upon a time—I’m talking to the younger folks reading right now—there wasn’t much else for us late-night people to do besides read or listen to the radio, because television stations in the pre-cable era called it quits sometime around 1 a.m. These days, we can stay up all night and do all kinds of things. My particular middle-of-the-night hobbies include playing video games and going to Twitter to annoy people in other time zones.

But my cherished guilty pleasure is tuning in to a network called MeTV, which specializes in vintage television, with shows from the 1950s to the 1980s. I love just about everything on MeTV because the shows offer the predictable and comfortable rituals of television from my childhood. An inevitable on-the-stand confession will always save an innocent client on Perry Mason. Officers Friday and Gannon on Dragnet will always exchange knowing looks when someone calls them “fuzz.” (Reed and Malloy will play the same game on Adam-12.) The regulars on The Carol Burnett Show will always bust each other up and break character.

These are all a lot of fun. But today I want to talk about the gems that are available only to the Nosferatus among us.

Private Eyes and Tough Guys

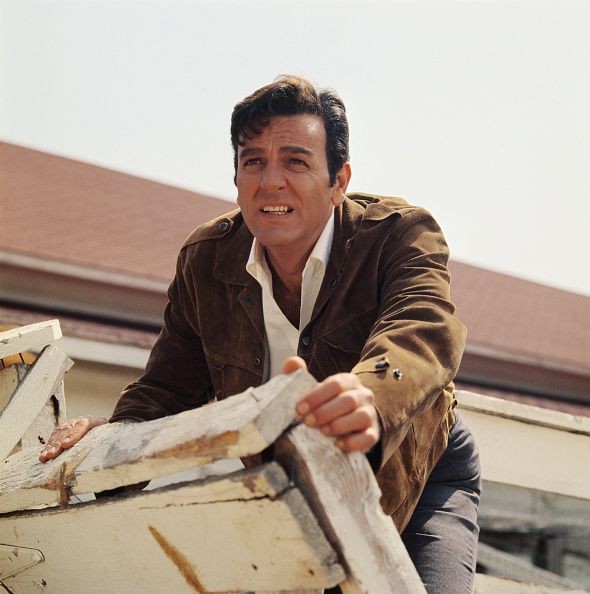

The night shift on MeTV starts with Mannix, a series about a tough private eye in Los Angeles. My late mother watched all these crime dramas, especially Mannix, and I started to watch the show again because it reminded me of her.

The show was a tad offbeat for its time: Actor Mike Connors, for example, insisted that his character, Joe Mannix, be an Armenian American like Connors himself. (As a Greek Orthodox kid, I loved that.) The plots were sometimes a little weird, too: Mannix was a former LA cop who served in Korea, and in at least two episodes, guys from his old unit in the Army wanted to kill him. It was, by the standards of the late 1960s, violent: In almost every show, poor Joe got a thorough beating, leading to concerned looks from his secretary, Peggy. (In some fairly progressive casting for that time, Peggy was played by Gail Fisher, an African American woman; Fisher won an Emmy for Mannix in 1970.)

Joe was a good guy, and he always tried to do the right thing, no matter the consequences and no matter how many times he got concussed. The show had a great opening sequence and a terrific jazz-waltz theme (composed by Lalo Schifrin, who also created the iconic Mission: Impossible spy cha-cha theme).

The theme to Cannon, however, sucked.

But Cannon, the show, did not entirely suck. Like Mannix, Frank Cannon was also a former LA cop turned private eye. He also lived in a cool apartment. He also had a phone in his car (yes, younger readers, this used to be a really amazing thing). But where Mannix was athletic and dashing, Cannon—played by the veteran actor and voice-over star William Conrad—was, shall we say, a man of substance. A big fellow. Conrad was 5 foot 9 and tipped the scales at around 250 pounds.

This, I imagine, was the high-concept pitch for the show to the "suits," the network executives:

Suits: What’s it about?

Producers: A widowed, obese, balding, middle-aged ex-cop who waddles around with his hands in his pockets as a private license in Los Angeles.

Suits: (Long pause.)

Producers: Uh, like Mannix, only fat, with less hair, and older.

Suits: Make the calls.

(Just to be clear, Conrad did not object to the word fat, and after Cannon, he starred in a successful, but not very good, 1980s show that was literally titled Jake and the Fatman.)

Now, as a kid, I didn’t watch Cannon, but again, my mother did. I didn’t get it. And yet here I am, in late middle age at 3:30 in the morning, with a bowl of popcorn balanced on my own considerable waistline. I am cheering on Frank Cannon even when I know it is impossible that he is actually winning a fistfight.

Maybe that’s why I like Frank: I can relate.

Cannon came from the prolific Quinn Martin, whose shop dominated the dramas of the 1970s, and Conrad won an Emmy despite the forgettable, Chinatown-lite plots and cheap sets. He was kind and jovial, and yet he could switch to hard and angry on a dime. He was also one of the greatest voices in mid-century America: He intoned the introduction for everything from the amazing classic The Fugitive to the dud Buck Rogers, both of which are on MeTV.

An Armenian detective? A chubby detective? Hey, here’s an idea: Let’s see if we can find a really old detective!

Your wish is granted. If you can make it to four in the morning, you can watch Barnaby Jones. Barnaby was played by Buddy Ebsen (from The Beverly Hillbillies), who starred in the show from age 63 to 71. You will be shocked to learn that his character is an LA private eye, but this time, he is retired—until he must reopen the shop and go into business with his daughter-in-law (the crush-worthy Lee Meriwether) to find out who killed his son.

Barnaby Jones was also a Quinn Martin show; it was originally intended as a spin-off of Cannon and there were a few crossover episodes with William Conrad. The target demo was, I assume, old and out-of-shape middle Americans who wanted to know why everyone in Hollywood’s version of Los Angeles was either being murdered or investigating a murder.

As usual, my mom was a sucker for this one, too. I will admit that I don’t “watch” Barnaby Jones now so much as I sort of drowse through it while my cat, Carla, sees if she can wake me up and get an extra late-night meal out of me.

But Barnaby Jones has a certain charm, not least because Ebsen just ambled through the show, a mailing-it-in performance that even now I admire for its loucheness. (It also has another great light-jazz theme, this time by Hollywood mainstay Jerry Goldsmith.) And it featured the lovely Morgan Fairchild, not once, but twice, which shows some on-the-ball casting.

After Barnaby waves a gun at a bad guy who gives up too easily, MeTV continues the theme of old, heavy, gruff guys at 5 a.m. with Highway Patrol, which starred the classic Hollywood hard-case, Broderick Crawford. Highway Patrol is not to be missed: It’s a 1950s ode to state cops, and it is mostly guys in fedoras talking tough to other guys in hats. Then Crawford rubs his wet nose on your face.

Wait, no, that’s Carla. The sun is nearly up and it’s time to go to bed.

Those are the weekdays. Saturday night is a special treat, full of shows my parents did not watch but that I adored.

Communist Giants and Talking Vegetables

Saturdays on MeTV start with Batman (a show I worshipped as a child) and the original Star Trek (which I still worship as an adult). But after midnight the real fun begins.

In 1972, ABC scared the bejeebers out of America with The Night Stalker, a TV movie about a reporter, Carl Kolchak, on the trail of a vampire in Las Vegas. Kolchak was played by the very likable Darren McGavin (the dad in A Christmas Story), and the movie was such a hit that it spawned a 1974 series that was (mostly) ridiculous. But some of the plots were satisfyingly creepy, and McGavin was honored many years later with a Kolchak-like cameo in The X-Files.

MeTV calls the whole evening Super Sci-Fi Saturday, but most of the night really belongs to Irwin Allen, the producer who made some of the dumbest, yet most lovable, shows ever made. (He was also the producer of the big-budget disaster movies The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno.)

Allen’s shows were fun, but generally not great. Consider Lost in Space. The first episodes of Lost in Space were grim, with a serious, almost documentary Cold War vibe. The nice American family trying to conquer space is betrayed and nearly killed by a traitor and saboteur from a certain unnamed country that you know is the Soviet Union. By the end of its run, it was so amazingly silly—with characters wearing silver face paint and playing sentient giant vegetables—that actor Guy Williams was suspended from the show for being unable to keep a straight face during filming.

But again, check in for the theme, composed by some guy who called himself “Johnny” Williams.

We then move to Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, another Allen show (based on a 1961 movie he directed) that began with Cold War themes in 1964 and ended up with pirate ghosts and rubber sea-monster costumes by 1968. But I loved the show, and I even built a model of the Seaview as a kid. Imagine my disappointment when I worked for the U.S. Naval War College, got on an actual attack sub, and found out that there was no all-glass observation deck.

At 3 a.m., you’re punchy enough for Allen’s Land of the Giants. I can’t really explain this one, and I doubt Allen could either. In the near future, a commuter spaceflight gets lost and ends up on a planet where our human heroes are only a few inches tall. But again, the Cold War was everywhere: The giant world is apparently something like Planet East Germany, with secret police and evil scientists and all that, which is why the crew can’t get home.

Another high-concept pitch meeting:

Suits: It’s what?

Producers: Irwin’s doing Lost in Space but it’s Communist giants.

Suits: (Long pause.)

Producers: Also, it’s got two very attractive women, a kid, and a dog.

Suits: You got one season, maybe two.

After that, it’s 4 a.m., and I am awake and ready for The Time Tunnel, a show about two scientists with a secret government project who become stranded as time travelers after running into a tunnel into time. (Wait, why did you have to run into a tunnel to travel in time?, you ask. My reasoned and considered answer is this: Shut up.) This was a nerd’s delight, combining history lessons and science fiction, sometimes with engaging drama. Once again, Lee Meriwether is on hand, this time in a white lab coat, frantically punching buttons to bring home the two colleagues who are falling through events everywhere from the Alamo to Pearl Harbor.

I assume, by this point, the meetings were short:

Suits: A tunnel?

Producers: Irwin Allen.

Suits: Here is some money.

The Irwin Allen festival is a truckload of cheese (except on the Land of the Giants planet, where it wouldn’t be enough for one hors d’oeuvre). But at 5 a.m., you have the opportunity to catch up on one of the greatest science-fiction programs ever made, a paranoid thriller from the Quinn Martin factory: The Invaders.

The Invaders took the idea of a lone person spotting aliens out in the boondocks, but then asked: What if that one person, instead of being some idiot out fishing in a swamp, was actually a really smart and brave professional and he wasn’t going to take no for an answer when telling his story?

They cast the very intense Roy Thinnes as the hero, architect David Vincent. The show had a real air of menace, not least because the invaders were indistinguishable from humans, but also because they had some scary tech, including a little gizmo that could kill you without a trace by inducing a heart attack. Over the course of the series, David starts gaining the upper hand, even at one point saving a town by negotiating a truce with the invaders. This was pretty intelligent stuff and it’s a shame the show never had a proper finale.

At 6 a.m., actor Gil Gerard jumps on your chest.

Sorry, my mistake, that’s Carla again. Buck Rogers in the 25th Century is on, and that horrible sound waking you is Mel Blanc voicing a robot that looks like a walking sex toy. Unwatchable. Time for bed.

Why, you might ask, would I bother watching all this other than to indulge some childhood nostalgia? (As if that’s not a good enough reason.)

I watch for many reasons. First, in my teaching career I was a scholar of the Cold War, and I am amazed at how much the Cold War permeates so many of the plots, especially on Saturday nights. (Likewise on Sundays, when I will sometimes catch Mission: Impossible as the Impossible Missions Force rescues some nuclear scientist from a generic communist country with a made-up language where signs such as EXIT or STOP are rendered in faux-Eastern European as EXJITC and SZTOHP and all that.)

Second, I sort of miss the clean, direct dialogue of the time before postmodern irony. Today, every line is a jaded observation or a tired smirk. I am reminded of a great moment in a 1996 episode of The Simpsons, in which two kids at a music festival are waiting for Homer to come on stage. “Oh, he’s cool,” one says in a deadpan. “Dude, are you being sarcastic?” the other asks. The first one hangs his head and says: “I don’t even know anymore.”

MeTV is television before all that. I love shows like The Boys and Stranger Things, but sometimes, it’s nice to visit a time when the characters just speak in completely ordinary sentences. “Peggy, get Lieutenant Tobias on the phone. Tell Adam I’m on my way.” “Be careful, Joe.” That’s all you need to know. It gives your brain a rest from peeling back layers of meaning. Joe’s going to meet Adam, and they’re going to do something dangerous, and Peggy is worried. That’s it.

I also love just observing these shows. They are visual time capsules, and I peer at street signs and homes and cars. I look carefully at storefronts and fashions. I watch characters talk on phones attached to walls. And I remember, as my wife and I often say, that the world once looked this way and we were part of it.

Finally, I watch because I miss my mother, who passed away 23 years ago. Watching TV with her was one of the few nice things in my otherwise tumultuous childhood. When Mannix solves the case or Barnaby rides off in his big car, I know that my mother probably saw the same episode, and that makes me smile. And then I drift off to sleep.