Putting Shakespeare on Trial in His Own Anti-Semitic Play

A new off-Broadway production masterfully recasts the playwright as the villain of “The Merchant of Venice”

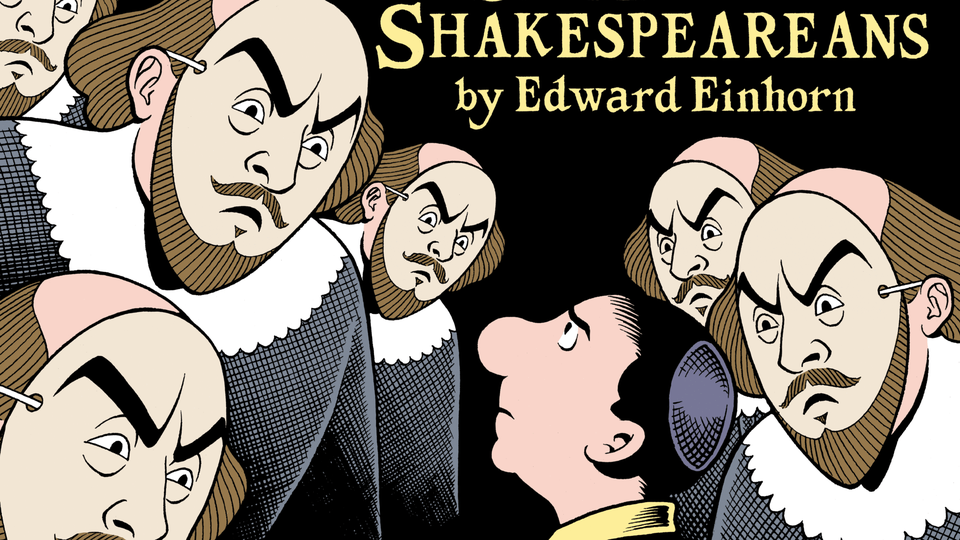

Although you wouldn’t know it from this newsletter, I don’t like consuming culture about anti-Semitism. This might sound surprising, given my chosen profession. But precisely because covering anti-Jewish prejudice is my job, experiencing art about it feels like work. I watch films and go to the theater to escape my professional obligations, not to be confronted by their contents. So when the playwright and director Edward Einhorn asked me to join a post-play discussion of his new work, The Shylock and the Shakespearians, I said yes but was honestly unsure what I would get out of it. I was wrong to worry. The play runs until June 17 at the New Ohio Theatre, and if you’re in New York City or inclined to stream the production from a distance, I’d highly recommend getting tickets while you still can.

At heart, The Shylock and the Shakespearians is a retelling of The Merchant of Venice, but with Shakespeare as the villain. Rather than obscure or sanitize the anti-Semitic nature of the original play, Einhorn places the prejudice front and center, and forces the audience to confront the ugly implications. For those in need of a refresher: The Merchant of Venice tells the story of Shylock, a stereotypical Jewish moneylender who demands a pound of flesh from a Christian man who is unable to pay his debt. The dispute goes to trial, the bloodthirsty Shylock refuses to relent, and he is ultimately foiled by a gentile cabal that coercively converts him to Christianity—forcing him into the footsteps of his daughter, Jessica, who married a gentile suitor. The work is one of Shakespeare’s comedies, because from the playwright’s perspective (and that of his target audience), everyone gets a happy ending.

This storyline is almost cartoonishly bigoted, yet scholars and artists have long defended the production, claiming that it humanizes its Jewish antagonist. Einhorn’s play refuses to accept these apologetics, and treats Shakespeare’s source material with the unstinting honesty it rarely receives on or off the stage. The Shylock and the Shakespearians understands that The Merchant of Venice is not a sympathetic portrait of a wronged Jew in an anti-Semitic society; rather, it is a vilification of the Jew that reflects the anti-Semitic prejudices of that society. Shylock’s infamous demand for a pound of flesh not only played off the historic slander of the blood libel—an ancient allegation that Jews coveted the blood of gentiles for perverse purposes, which had long fueled Jewish persecution—but also ensured that the libel reached new audiences for centuries. As Einhorn’s production repeatedly underscores, The Merchant of Venice was not a critique of anti-Semitism; it was a purveyor of anti-Semitism.

In the play, the bigots that menace Jews and other undesirables in the streets of Venice wear masks with Shakespeare’s face on them, looking up to him as an idol. They use his vocabulary—referring to Jews as “Shylocks”—and believe his claims about the Jewish hunger for gentile flesh, no matter how many times this is denied by actual Jews. Through its dialogue and storytelling, the production also offers a clinic on the nature of anti-Semitism, which operates in its fictional Europe not merely as a personal prejudice, but as a form of structural exclusion, as well as a conspiracy theory that blames Jews for social and political problems. This, Einhorn argues, is the world that Shakespeare shaped.

With Shakespeare and his followers recast as the play’s antagonists, Shylock—“Jacob the jeweler,” in Einhorn’s retelling—and his daughter, Jessica, become protagonists, struggling to navigate a society that refuses to accept them, each making different but understandable choices amid impossible circumstances. (The two characters are powerfully portrayed by performers Jeremy Kareken and Yael Haskal, respectively.) Inevitably, Shakespeare’s comedy ends in tragedy.

That’s not to say that the play loses its sense of humor. The Merchant of Venice contains multiple romantic subplots, which are rendered here in somewhat slapstick fashion. But some of the best jokes come at the expense of the original play itself. “You hate me … for I am a Christian,” declares the anti-Semitic merchant Antonio. “No, for you are an asshole,” retorts Jacob. (Before you see the production, I recommend at least skimming a summary of The Merchant of Venice so that you can fully appreciate the way Einhorn toys with its elements.)

I don’t believe that we should reflexively jettison older art that is tainted by the bigotry of its time. In fact, the most powerful experience I’ve ever had with Shakespeare was a classroom performance of The Merchant of Venice in my Orthodox Jewish high school. The student who took on the role of Shylock was incredibly talented and transformed the production’s anti-Semitic caricature into a sympathetic character. Talented performers have regularly rescued Merchant from itself, redeeming the play from its prejudices.

But just because great actors have the ability to subvert Shakespeare’s intentions doesn’t change what those intentions were—and what his play actually says. By looking the text in the eye and compelling audiences to do the same, The Shylock and the Shakespearians does something no production of The Merchant of Venice ever could.

The Shylock and the Shakespearians runs through June 17 at the New Ohio Theatre, in New York City. Tickets are available for both the live performance and a livestream.

P.S. Regular readers know that although I think art against anti-Semitism is important, I believe we need just as much art that expresses who Jews are, not just who they are not. Toward that end this week, I released this illustrated lyric video for one of the songs off my recent original Jewish music album. I hope you enjoy! You can find the whole album here.

Thank you for reading this edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the unexplored intersections of politics, culture, and religion. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already. And as always, you can send your comments, critiques, and questions to deepshtetl@theatlantic.com.