How to Win an Argument but Lose the Plot

Harvard’s Claudine Gay was right that context matters for campus anti-Semitism. It does at the International Court of Justice too.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

In 2003, Warner Bros. released the much-hyped Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, some 12 years after the previous installment in the franchise. The celebrated critic Roger Ebert was not impressed. The movie, he wrote, “abandons its own tradition to provide wall-to-wall action in what is essentially one long chase and fight, punctuated by comic, campy or simplistic dialogue.” Unfazed, the film’s promoters proudly emblazoned Ebert’s verdict on their advertising. Well, four words of it: “Wall-to-wall action.”

Context matters. It can completely change the meaning of a phrase or an act. And yet, since October 7, many otherwise thoughtful and intelligent people have abandoned context and turned themselves into the political equivalent of Terminator 3’s PR team. When the subject is not the movies but matters of the Middle East, the consequences of this sleight of hand are far graver than some dubious promotional puffery.

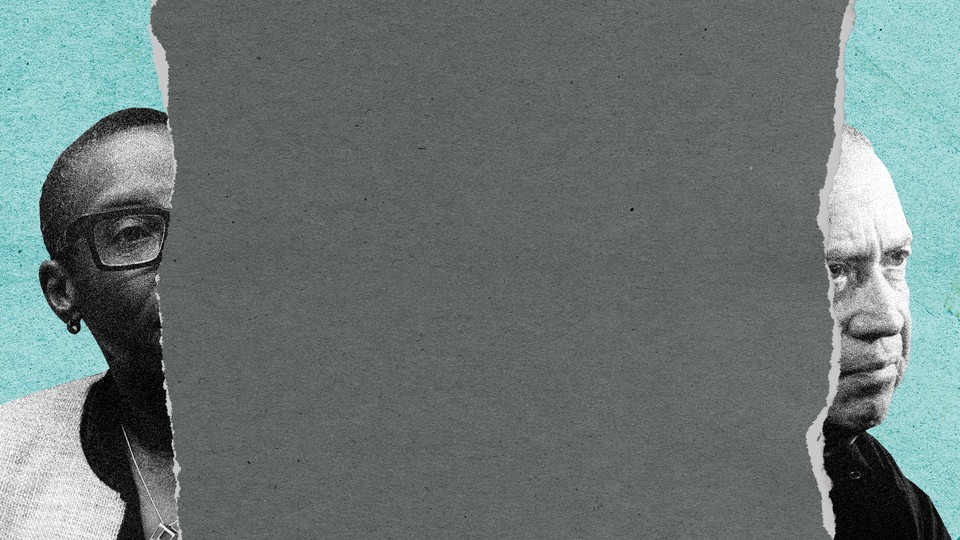

Exhibit A: The U.S. Congress. In December, Republican Representative Elise Stefanik grilled Claudine Gay, the then-president of Harvard University, about anti-Semitism on campus. The exchange went viral and ultimately triggered the events that led to Gay’s resignation following plagiarism charges. The irony is that in the dispute that precipitated her ouster, Gay was right and Stefanik was wrong.

Stefanik opened by invoking slogans that have become commonplace at pro-Palestinian rallies: “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” and “Globalize the Intifada.” These phrases, Stefanik said, were calls for the murder of Jews. She then cannily conflated the chants with advocacy for the genocide of Jewish people. But Gay and her fellow college presidents at the hearing refused to accept this framing of the slogans. When asked point-blank whether “calling for the genocide of Jews violates Harvard[’s] code of conduct,” Gay replied, “It depends on the context.” With this answer, Gay was not condoning genocidal advocacy—she had explicitly called such speech “abhorrent” earlier in the proceedings. Rather, Gay was rejecting Stefanik’s assumption that the specific slogans she’d mentioned always violated Harvard’s code of conduct and necessarily constituted calls for actual genocide. In this, Gay was correct.

Terrorist groups like Hamas do indeed invoke “From the river to the sea” to advocate for the violent elimination of Israel. But many of the college students and others who recite these words at rallies don’t even know what they mean. A survey by the UC Berkeley political scientist Ron Hassner found that “only 47% of the students who embrace the slogan were able to name the river and the sea”; some misconstrued the mantra as a call for a two-state solution. Ignorance isn’t genocidal advocacy; it’s the default state of most students, which is why they go to school in the first place. (Notably, Hassner found that 75 percent of students downgraded their opinion of the slogan after being shown a map.)

At the same time, some more knowledgeable activists understand “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” as a call for a binational or secular democratic state for both Israelis and Palestinians. Polls show that Palestinians and Israelis on the ground overwhelmingly reject being combined into a shared state, but utopianism isn’t anti-Semitism either. Similarly, “Globalize the Intifada” undoubtedly evokes the many horrific suicide bombings during the Second Intifada that targeted Israeli civilians in restaurants, clubs, and buses in the early 2000s; but the word Intifada itself simply means “shaking off,” and can refer to the First Intifada, which had significant nonviolent components.

Whether slogans like these constitute incitement to violence or targeted harassment also depends on where they are expressed—a Facebook post is different from a rally in a public space, which is different from someone shouting at visibly Jewish students in the street. The intention and situation of the speaker matter, not just the words.

Put another way, whether these phrases constitute incitement to genocide is indeed, as Gay put it, context-dependent. One cannot understand the meaning of such chants, or the meaning of Gay’s replies to Stefanik, without the full context. But none of that necessary background was included in the short video clips that circulated online after the hearing.

A similar scene unfolded last month at the International Court of Justice, but with the charges of genocidal incitement reversed. Lawyers for South Africa leveled these allegations at Israel, and central to their claim were several shocking statements from Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant: “Gaza will not return to what it was. We will eliminate everything.” “We are fighting human animals.” These quotes were crucial to the case, because under the Genocide Convention, the crime entails not simply destruction but demonstrable intent among top decision makers “to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

But as I documented last month, the quotes attributed to Gallant were either incorrect, truncated, mistranslated, or stripped of essential context. In each case, the defense minister was referring to destroying Hamas, not Gaza or Gazans. And the proof was all available on video. On October 10, speaking at the Gaza border to soldiers and police who had repelled the Hamas terrorists who murdered more than 1,000 Israelis, Gallant said: “Gaza will not return to what it was before. There will be no Hamas. We will eliminate it all.” (Emphasis added. The New York Times, the Associated Press, NPR, and The Guardian, among others, corrected their quotations following my report.) In the same short speech to the border defenders, Gallant explained to whom he was referring as “human animals”: “You have seen what we are fighting against. We are fighting against human animals. This is the ISIS of Gaza.” Given that Gallant was speaking directly to those who had battled Hamas, and that both American and Israeli officials have likened the group’s acts to those of the Islamic State, there can be no mistake about what the defense minister meant. The context is key.

In the ICJ’s preliminary ruling on January 26, which did not demand a cease-fire but called on Israel to avoid potential genocide, the court cited Gallant’s words. But instead of using the selective misquotes from South Africa’s brief, the ICJ revised the language to include the missing material. This makes for odd reading, because Gallant’s words no longer support the argument they had been adduced to make—that he was targeting Gazans, not Hamas—suggesting that the ICJ had already written this section and simply updated the quotes at the last minute without updating its argument.

Further evidence that the ICJ didn’t carefully review these quotes comes from another Gallant line that the court included as an indication of genocidal intent: “I have released all restraints … You saw what we are fighting against.” It is reasonable to wonder whose restraints Gallant was removing, and for what purpose, but the ICJ provides only an ellipsis. Fortunately, the context of these remarks is also captured in the same video. Here is what Gallant actually said: “I have released all the restraints. We are activating everything. We are taking off the gloves. We will kill anyone who fights against us.” As a writer, I have plenty of literary objections to Gallant’s reliance on macho clichés, but as before, he is clearly referring to activating Israel’s armed forces to target combatants, not civilians.

Plenty of other context points to the same conclusion. On October 8, Gallant declared, “Hamas has become the ISIS of Gaza. In this war, we are fighting against a murderous terrorist organization that harms the elderly, women, and babies.” On October 12, the defense minister told NATO, “The IDF will destroy Hamas.” On October 27, while urging Gazan civilians in the north to evacuate to the south, Gallant said, “We are not fighting the Palestinian multitude and the Palestinian people in Gaza.” The list goes on. The only way to misunderstand Gallant’s intentions is to ignore pretty much everything he has said on this subject.

Such an error is consequential, because in reality, far from abetting the Israeli hard right, Gallant has been standing in its way. Last week, thousands of settler activists held a celebratory conference in Jerusalem that was attended by 15 of the 64 members of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s governing coalition. The purpose of the gathering was to plan the resettlement of Gaza, following the “voluntary emigration” of its Palestinian residents. This euphemism for ethnic cleansing was helpfully clarified by one minister from Netanyahu’s Likud Party, who explained, “‘Voluntary’ is at times a situation you impose until they give their consent.” The next day, Axios reported that Gallant told the Biden administration that he would not allow settlements in Gaza, reiterating a position he had previously taken when he declared that postwar Gaza should be governed by Gazans with international assistance.

Just as decontextualizing campus chants can wrongly lead to pro-Palestinian activists being tarred as genocidal anti-Semites, the ICJ’s misrepresentation of Gallant miscast an opponent of Israel’s hard right as one of its allies. As it turns out, whether it’s “From the river to the sea” or “Eliminate it all,” context matters—and that cuts both ways.

Political partisans tend to appeal to context when it supports their stance and ignore it when it complicates their narrative. This approach is useful if you are trying to win an argument, but it is deeply counterproductive if you are trying to understand reality. For the rest of us, stories like these are a reminder that there are better ways to learn about the world than from incendiary viral videos and selective citations.