How Baseball Explains the Limits of AI

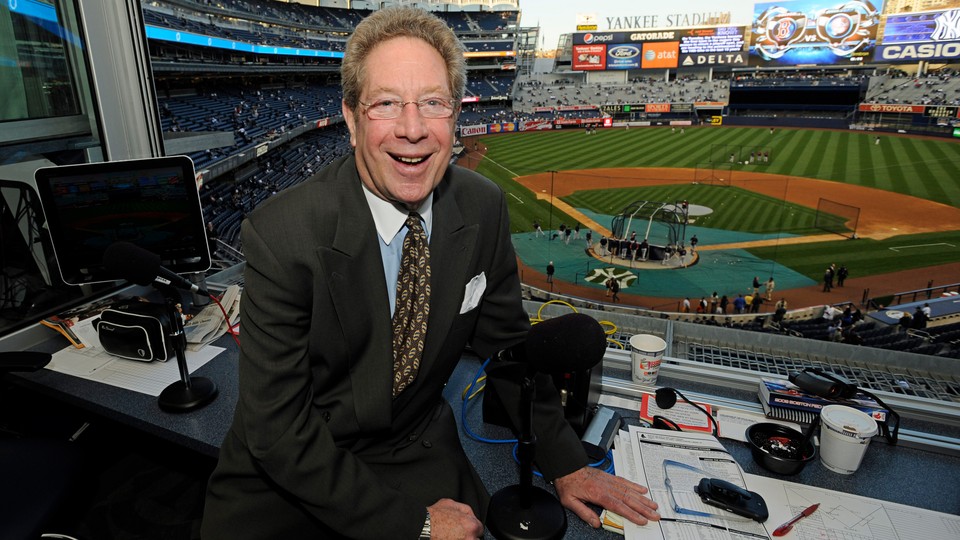

The iconic Yankees broadcaster John Sterling reminds us that what makes us human cannot be imitated.

My family never had cable or watched much TV when I was growing up, so I experienced baseball through my bedside radio. Every night during the regular season, I’d follow the Yankees vicariously through the commentary of the announcer John Sterling, who delivered the play-by-play alongside Michael Kay and later Suzyn Waldman, herself a trailblazer in the world of sportscasting.

I can still recite some of Sterling’s calls from memory: David Wells! David Wells has pitched a perfect game. Twenty-seven up. Twenty-seven down. Baseball immortality for David Wells! And the Yankees win … thuh-uh-uh Yankees win! The one time I ever arrived at the ballpark early as a fan wasn’t to get some disposable player bobblehead—it was to make sure I got a T-shirt featuring John and Suzyn captioned with the former’s signature line, That’s baseball, Suzyn.

Those moments have reverberated in my mind this week, after the 85-year-old Sterling announced his retirement following 36 years and 5,631 games on the job—including seven world championships. He was honored yesterday at Yankee Stadium. All the usual accolades have rolled in: Sterling is “inimitable,” “one of a kind,” “irreplaceable.” There’s some truth to these clichés. With his combination of gravitas and camp—he is both beloved and bemoaned for his personalized home-run calls for every Yankee player—Sterling is certainly unlike any other announcer in the game. But as a reporter who covers technology and its effects on our culture, I found myself wondering whether the claims about the singular and irreproducible nature of Sterling’s voice were behind the times.

In January, scammers produced a completely convincing robocall in which President Joe Biden seemingly urged New Hampshire Democrats to sit out the state primary. Thanks to advances in AI technology, it has become trivially easy to digitally clone your own voice or anyone else’s. These developments raise the question: What makes a voice unique, and is anyone’s truly inimitable anymore? Couldn’t a simulated Sterling, trained on years of his play-calling, credibly carry on his commentary long after he is gone? Couldn’t his likeness easily be licensed and reanimated by some enterprising entertainment company?

The answer is no—and the reason is that there are certain things that artificial intelligence, no matter how advanced, can never replace. What makes a sports announcer great is not just the cadences of their commentary, but their ability to convey what they are experiencing and sweep the listener up in it. The best play-by-play commentators conscript us into a conspiracy of concern: Together, we hang on to every pitch, swing, and miss. An announcer is special less for turns of phrase than for the ability to inhabit this moment with us, sharing our excitement, suspense, surprise, and heartbreak.

By definition, a computer cannot provide this. No matter how much a robo-Sterling sounded like Sterling, it would never be able to convince us that it cared about the game like Sterling, because it wouldn’t. An AI might manage to copy his campiness, but it could never reproduce the feeling of sharing an experience. Fundamentally, the automated imitation of emotion isn’t exhilarating; it’s alienating—a soulless simulacrum lacking the essence of human interaction.

This truth holds not just for sports announcing but for other genres of artificial audio as well. AI narration can capably read you this article and perform the utilitarian function of conveying the information into your ears, but it cannot produce a heart-wrenching ballad of loss and longing.

Well, technically, it can. The music generator Suno has made headlines recently for its ability to impressively churn out songs in countless genres and styles. Last month, the journalist Ross Anderson used the tool to generate an entertaining concept album that included a Cocomelon-style ditty extolling the joys of child labor and a souped-up sea shanty about a never-ending Biden-Trump rematch.

I myself was able to get Suno to produce a passable folk lament for the lost Jewish community of Vilna—a historic home to Jewish learning, culture, and political ferment that was destroyed by the Holocaust. “On the cobblestone roads, melodies filled the air / from the Yiddish theater, the souls were laid bare,” the virtual vocalist croons. “But darkness approached, a storm began to brew / The vibrant city of Vilna, its fate it could not undo.”

But the song is fundamentally a failure for the same reason that a pseudo-Sterling would be: The listener does not actually believe that the speaker cares about the subject. Just as the AI is not actually invested in the baseball game or the Yankees, it does not actually mourn the loss of Jewish life in Vilna or wonder what the city would have been like to visit before the destruction. The more we ask of our music, the less AI will be able to deliver, which is why these generators are best suited to producing bubblegum pop songs or catchy dance anthems rather than anything more existentially complex. We have trouble empathizing with something that we recognize is produced without empathy.

John Sterling means something special to Yankees fans. But he also taught me something beyond baseball: that certain aspects of the human experience can never be replicated or replaced. What makes us who we are is not just the stories we tell, but the stories we share and inhabit together.