The Unlikely World Leader Who Just Dispelled Musk’s Utopian AI Dreams

Benjamin Netanyahu is not buying what the billionaire is selling. He may have a point.

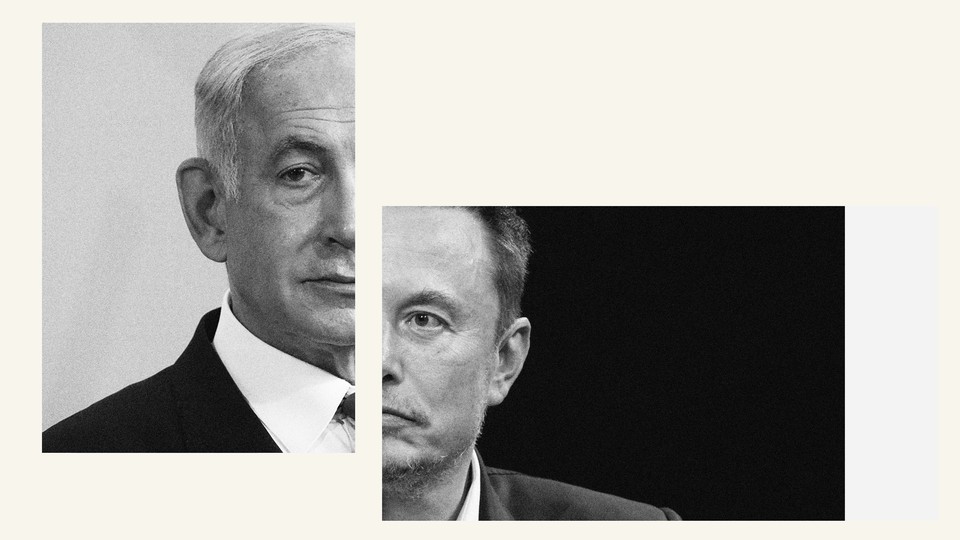

On Sunday, just before heading to the United Nations, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited Elon Musk in San Francisco. Their livestreamed rendezvous held obvious appeal for both men. The embattled Netanyahu would get to show his voters that he could command the attention of the world’s richest man. Musk would get to show the world that he had a Jewish friend, days after getting caught up in an anti-Semitism scandal on his social-media platform. The meeting was, essentially, a glorified photo op.

That’s how it started, at least.

At the outset, Netanyahu called Musk the “Edison of our time.” Musk returned the favor by not challenging Netanyahu’s insistence that his proposed judicial reforms—which have provoked the largest protest movement in Israel’s history—would make the country a “stronger democracy.” (“Sounds good,” the mogul replied.) The two men discussed their shared love of books and then, after about 40 minutes, wrapped up their exchange, at which point most people tuned out. But that’s precisely when things got interesting.

Musk and Netanyahu returned to the broadcast for a panel discussion about artificial intelligence with the MIT scientist Max Tegmark and Greg Brockman, the president of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT and the image generator DALL-E. What happened next received scant media coverage, because reporters were there to see a right-wing magnate hobnob with a right-wing world leader, not to listen to the two discuss AI with some nerds. Which is why many missed the moment when Netanyahu went off-script and challenged the utopian dreams of Musk and his fellow technologists.

Their conversation wasn’t just about AI. It was a confrontation of worldviews—a clash between American entrepreneurs who believe in the promise of transformational change for humanity and a deeply cynical Israeli politician who does not. And it was a glimpse into the profoundly pessimistic mind of one of the world’s most polarizing and influential leaders, revealing not just his philosophy of technology, but his understanding of people and power, and why he has led his country the way he has.

It began with a simple question from Netanyahu: “How do we inject a measure of responsibility and ethics into this exponentially changing development?” Musk, who previously signed a letter calling for a pause in AI development to ensure its safety, is not unaware of these concerns, and conceded their merit. “Just as Einstein didn’t expect his work in physics to lead to nuclear weapons, we need to be cautious that even with the best of intentions … we could create something bad,” he replied. “That is one of the possible outcomes.”

But as Netanyahu soon made clear, when it comes to AI, he believes that bad outcomes are the likely outcomes. The Israeli leader interrogated OpenAI’s Brockman about the impact of his company’s creations on the job market. By replacing more and more workers, Netanyahu argued, AI threatens to “cannibalize a lot more jobs than you create,” leaving many people adrift and unable to contribute to the economy. When Brockman suggested that AI could usher in a world where people would not have to work, Netanyahu countered that the benefits of the technology were unlikely to accrue to most people, because the data, computational power, and engineering talent required for AI are concentrated in a few countries.

“You have these trillion-dollar [AI] companies that are produced overnight, and they concentrate enormous wealth and power with a smaller and smaller number of people,” the Israeli leader said, noting that even a free-market evangelist like himself was unsettled by such monopolization. “That will create a bigger and bigger distance between the haves and the have-nots, and that’s another thing that causes tremendous instability in our world. And I don’t know if you have an idea of how you overcome that?”

The other panelists did not. Brockman briefly pivoted to talk about OpenAI’s Israeli employees before saying, “The world we should shoot for is one where all the boats are rising.” But other than mentioning the possibility of a universal basic income for people living in an AI-saturated society, Brockman agreed that “creative solutions” to this problem were needed—without providing any.

The conversation continued in this vein for some time: The AI boosters emphasized the incredible potential of their innovation, and Netanyahu raised practical objections to their enthusiasm. They cited futurists such as Ray Kurzweil to paint a bright picture of a post-AI world; Netanyahu cited the Bible and the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides to caution against upending human institutions and subordinating our existence to machines. Musk matter-of-factly explained that the “very positive scenario of AI” is “actually in a lot of ways a description of heaven,” where “you can have whatever you want, you don’t need to work, you have no obligations, any illness you have can be cured,” and death is “a choice.” Netanyahu incredulously retorted, “You want this world?”

By the time the panel began to wind down, the Israeli leader had seemingly made up his mind. “This is like having nuclear technology in the Stone Age,” he said. “The pace of development [is] outpacing what solutions we need to put in place to maximize the benefits and limit the risks.”

It might seem strange that Netanyahu so publicly challenged the ambitions of Musk and his colleagues, especially at what was meant to be a softball sit-down. But Netanyahu’s resistance to optimistic assurances about future progress is core to his worldview—a worldview that has long shaped his approach to the politics of Israel and the world around it.

In December 2010, a street vendor in Tunisia set himself on fire to protest state corruption, triggering protests across the Middle East, as part of what became known as the Arab Spring. At the time, Netanyahu was unimpressed, arguing that the region was going “not forward, but backward.” Israeli officials likened the demonstrations to those that ushered in Iran’s theocracy in 1979. But many Western leaders, including President Barack Obama, hailed the upheavals as the dawn of a new liberal era for that part of the world. “The events of the past six months show us that strategies of repression and strategies of diversion will not work anymore,” Obama said in a State Department speech in May 2011. “A new generation has emerged. And their voices tell us that change cannot be denied.” He continued:

In Cairo, we heard the voice of the young mother who said, “It’s like I can finally breathe fresh air for the first time.”

In Sanaa, we heard the students who chanted, “The night must come to an end.”

In Benghazi, we heard the engineer who said, “Our words are free now. It’s a feeling you can’t explain.”

In Damascus, we heard the young man who said, “After the first yelling, the first shout, you feel dignity.”

Today, Cairo is once again under military dictatorship. Sanaa is in ruins, a casualty of Yemen’s ongoing civil war. Benghazi is where an American ambassador was murdered in a failed Libyan state. Last May, Damascus’s Bashar al-Assad was welcomed back into the Arab League, after he brutally quelled the rebellion against his Syrian regime, including by using chemical weapons. And this week, Tunisia’s authoritarian president bizarrely connected “Zionist” influence to a storm that ravaged the area.

Netanyahu was a naysayer about the Arab Spring, unwilling to join the rapturous ranks of hopeful politicians, activists, and democracy advocates. But he was also right. This was less because he is a prophet and more because he is a pessimist. When it comes to grandiose predictions about a better tomorrow—whether through peace with the Palestinians, a nuclear deal with Iran, or the advent of artificial intelligence—Netanyahu always bets against. Informed by a dark reading of Jewish history, he is a cynic about human nature and a skeptic of human progress. After all, no matter how far civilization has advanced, it has always found ways to persecute the powerless, most notably, in his mind, the Jews. For Netanyahu, the arc of history is long, and it bends toward whoever is bending it.

This is why the Israeli leader puts little stock in utopian promises, whether they are made by progressive internationalists or Silicon Valley futurists, and places his trust in hard power instead. As he put it in a controversial 2018 speech, “The weak crumble, are slaughtered and are erased from history while the strong, for good or for ill, survive. The strong are respected, and alliances are made with the strong, and in the end peace is made with the strong.” To his many critics, myself included, Netanyahu’s refusal to envision a different future makes him a “creature of the bunker,” perpetually governed by fear. Although his pessimism may sometimes be vindicated, it also holds his country hostage. But the Israeli leader sees himself as a realist who does whatever it takes to preserve the Jewish people in an inherently hostile world. (Likewise, he also does whatever it takes to preserve his own power, because he believes that no one else can be trusted to do what he does.) This is why Netanyahu has gradually aligned his country with strongmen across Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. And it’s why he resists any concessions to Israel’s Palestinian neighbors, seeing the conflict as a zero-sum game.

In other words, the same cynicism that drives Netanyahu’s reactionary politics is the thing that makes him an astute interrogator of AI and its promoters. Just as he doesn’t trust others not to use their power to endanger Jews, he doesn’t trust AI companies or AI itself to police its rapidly growing capabilities.

“Life is a struggle,” he told the technologists in San Francisco. “It’s defined as a struggle, where you’re competing with forces of nature or with other human beings or with animals, and you constantly better your position. This is how the human race has defined itself, and our self-definition is based on that—both as individuals, as nations, as humanity as a whole.”

Ever the optimist, Musk has staked his electric cars, his rockets to Mars, and his AI algorithms on the assumption that humanity can transform its situation and build its way to a better tomorrow. But Netanyahu believes that all of these technological advances are only as good as the humans who operate them—and humans, he knows, don’t have the best track record.