The Most Consequential First Amendment Case This Term

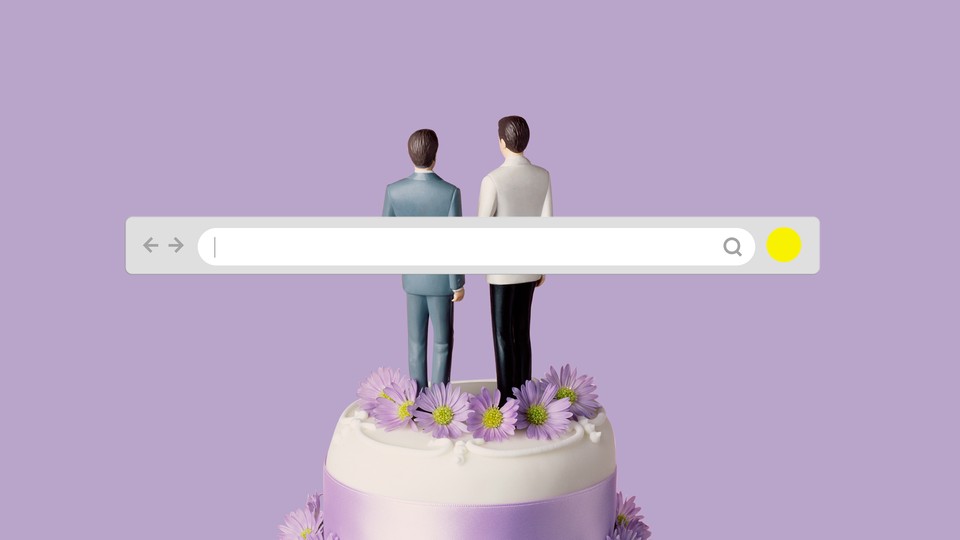

303 Creative v. Elenis isn’t about LGBTQ rights, as many people believe it to be, but about what constitutes speech.

On Monday the Supreme Court is going to hear oral arguments in what may well be the most consequential First Amendment case of the term. It will be cast as a culture-war case, as a fight between LGBTQ rights and free speech, but it’s not truly that. It’s something else, something far more significant.

The case is called 303 Creative v. Elenis, and the precise issue in the case is simple: “whether applying a public-accommodation law to compel an artist to speak or stay silent violates the free speech clause of the First Amendment.” But behind that simple statement is hidden a frankly bizarre legal doctrine, one that the Supreme Court has to address or it threatens the very nature of artistic freedom itself.

The petitioner in the case, Lorie Smith, is a website designer who, according to her Supreme Court brief, intends to design custom wedding websites, but she refuses to design websites that advance ideas or causes she opposes. As a theologically conservative Christian, she opposes same-sex marriage and will not design websites celebrating gay weddings, though she says she would work with gay clients on other, non-same-sex-marriage websites.

So far this all sounds like a rather conventional culture-war dispute, and the legal framework for deciding it is also quite conventional. As a general matter, if a vendor or company is providing a good or service—such as, say, a barbecue restaurant serving barbecue sandwiches—then it doesn’t enjoy a constitutional right to refuse service to customers on the basis of status or identity.

But though the state can demand that businesses provide goods and services to all comers without regard to race, sex, sexual orientation, and other protected categories, it cannot demand that businesses or individuals engage in speech proclaiming messages that they oppose, and, as Smith argues, designing websites is a form of speech.

Two cases highlight the distinction between services and speech. In a 1968 case called Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, the Supreme Court said that it was “patently frivolous” to claim that the free-exercise clause of the First Amendment gave a sandwich-shop owner the right to refuse to serve Black customers.

The clear prohibition against compelled speech, by contrast, dates back to a 1943 case called West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette. At the height of World War II, the Supreme Court held that West Virginia could not make students salute and pledge allegiance to the American flag. The decision contained arguably the most famous single sentence in American First Amendment jurisprudence: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

Thus, the key question in 303 Creative should be whether Smith was denying a service on the basis of status or refusing to engage in speech because she disagreed with its message. If it’s the former, she loses. If it’s the latter, she wins. This was the essence of the debate around a similar 2017 case, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission.

Jack Phillips, the owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop, refused to design a custom wedding cake for a same-sex wedding, and the oral argument in the case was intensely focused on the line between service and expression. Was designing a custom cake really a constitutionally protected expressive act? Ultimately, the Court punted on that key question, deciding by a 7–2 margin that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had violated Phillips’s rights to free exercise of religion by specifically targeting him because of his faith.

But here’s where 303 Creative gets truly strange. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals held that Smith was engaging in “pure speech” and that Colorado was compelling her speech, but it ruled for Colorado anyway. The reasoning in the majority opinion was extraordinary.

“This case does not present a competitive market,” the court said. “Rather, due to the unique nature of Appellants’ services, this case is more similar to a monopoly. The product at issue is not merely ‘custom-made wedding websites,’ but rather ‘custom-made wedding websites of the same quality and nature as those made by Appellants.’ In that market, only Appellants exist.”

Thus, because Smith possessed a monopoly over her own services, the state had a heightened interest in ensuring access to her work.

That is a truly remarkable legal doctrine, one that would vitiate the First Amendment rights of artists who sell their art in the marketplace. After all, every artist has a monopoly over the production of their own art (copyright complexities aside). Does that mean that they’re subject to heightened state regulation? Does that mean that Barnette is diminished when paying customers demand an artist’s work?

The case is so remarkable that I came out of legal semiretirement to participate. I filed an amicus brief on behalf of a number of conservative state family-policy organizations. In that brief I contrasted the right of major corporations to speak (or refuse to speak) in the marketplace of ideas with the now-contested right of a single artist to speak (or remain silent) with her own work. As I wrote, “If rights of conscience attach to corporations worth trillions, shouldn’t they also attach to a single artist whose alleged ‘monopoly’ is merely in the sweat of her own brow?”

Because the case involves a clash between Christian expression and the desire to protect LGBTQ Americans from discrimination, the culture-war frame is inevitable. But that framing distorts the analysis. This case isn’t about religious liberty versus gay rights but rather about freedom of expression for all artists, regardless of their views. And every artist is entitled to decide what they will say, regardless of the identity of the person demanding their art—or to not say anything at all.