In March 2008, I experienced the worst night of my life. I was downrange in Iraq, serving as the squadron judge advocate—the lawyer—for the Second Squadron, Third Armored Cavalry Regiment. It was the height of the surge, and my unit had been deployed to one of the most violent regions of the country.

Nights were always tense. Because most of our combat operations were at night, that’s when we engaged the enemy. That’s when we took casualties. And that evening, a young soldier burst into my tiny office in Forward Operating Base Caldwell, a small base in eastern Diyala Province. “Captain French,” he said, “you’re needed in the TOC. Now.”

In Army language, the TOC is the tactical operations center, the “brain” of an Army unit at war. That’s where an officer called a battle captain helps manage and direct the fight, like a conductor leading a deadly symphony.

A torrent of information flows into a TOC, especially in a time of crisis. Radio reports, text messages from the Army’s Blue Force Tracker system, and drone feeds can overwhelm the senses.

When I arrived, I saw grim faces and eyes shining with tears. The news was very bad. A Humvee had been hit by a command-detonated improvised explosive device. Multiple troopers were dead. At least one had grave injuries. In moments like this, your mind splits in two. One part is awash in uncertainty and grief—we had fewer than 1,000 soldiers on our small base, and by this point in our deployment, we all knew one another. We knew that friends were likely in that burning Humvee.

The other part of your mind knows there’s a job to do. So you push the grief away and focus. Was this a single strike, or was it the start of an ambush? Are medevac helicopters on the way? Do we need to deploy the quick-reaction force? Life-and-death decisions flow one after another until the crisis passes.

Why was I there? The short answer is that Army lawyers were constantly present during the Iraq War. We were fighting a complicated counterinsurgency, and complex rules of engagement governed our uses of force. For better and for worse, commanders often consulted their JAG officers—the military’s lawyers—before ordering responsive fires.

On other occasions, I’d helped make tough, terrifying decisions, but this time there was nothing for me to do. We never saw the enemy. We never even had the chance to make a choice about whether to respond. Instead, I watched and waited until more terrible news arrived.

We lost four men: a civilian interpreter named Albert Haroutounian and three soldiers—Specialist Donald Burkett, Sergeant Phillip Anderson, and my friend Captain Torre Mallard. The news hit us all like a punch in the face. Every person in the TOC was close to one or more of those guys, as close to them as a brother.

The shock of the moment caused me to reflect once again on the longer answer to the question why. Why was I there, really?

In October 2005, I was living the good life. I was president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a small civil-liberties nonprofit located in Philadelphia. It was a dream job. I led a bipartisan team of idealistic young civil libertarians, and I lived in a penthouse apartment in the city’s center with my wife and two kids. I was 36 years old.

I’d supported the war in Iraq. I didn’t really have any kind of national voice, but to the extent that my opinion mattered, I’d voiced it loudly and vociferously. Saddam Hussein had to go. We now know the rest of the story. We toppled his regime in a lightning war but then faced a grinding insurgency. By late 2005, the Sunni-Shia civil war raged, American casualties mounted, and the Army struggled to meet its recruiting targets. Who wanted to fight and die in what seemed like a losing war?

One evening, at home in Philadelphia, I read the story of a Marine officer who had been wounded in Anbar province. He’d used the reporter’s satellite phone to call his wife and two kids and tell them that he was hurt but he’d be okay. At that instant I was hit with a burning sense of conviction. How could I support a war I wasn’t willing to fight?

With my wife’s blessing, I enlisted. I walked to the recruiting office in downtown Philly and asked about getting an age waiver and joining the JAG Corps. I didn’t have an infantry body, but I did have a legal mind.

What followed would have been pure comedy if it hadn’t had serious consequences. I almost flunked my initial physical. I was so nervous, my blood pressure spiked. The very first time I tried to run myself back into shape, I pulled a hamstring. Let’s just say I wasn’t the most impressive person in officer basic training at Fort Lee, Virginia, in the hot summer of 2006.

Everyone called me “Professor” (I’m a former Cornell Law School lecturer), and the drill instructors seemed to delight in saying things like, “Professor, get in the plank position,” or, “Professor, drop and give me 20.”

But I made it through, and in June 2006, I graduated from officer basic training humbled, sore, and covered in hives. (Two days before graduation, I had dived into a patch of poison ivy in the middle of a simulated ambush—another great moment of high comedy.)

By April 2007, I’d finished my Army legal training. In June I volunteered to go to Iraq. In September I got orders to join the Third Armored Cavalry Regiment, and by November I was in the country. The next 11 months would be the hardest of my life.

I’ll never forget landing at Forward Operating Base Caldwell in the very early-morning hours of Thanksgiving Day, 2007. After a low and fast nighttime helicopter flight across the Iraqi countryside (the first helicopter flight of my life), I was exhausted and intimidated. When I landed, one of the troop commanders saw my wide eyes, put his arm around me, and said, “Lawyer, if you live through this, this is your most important year.” He was right.

Serving as a JAG officer in a combat-arms unit isn’t exactly the stuff from which movies are made. You’re definitely not the hero. You serve the heroes. And there were heroes in our midst. One sergeant was shot in the neck yet stayed in his gun turret, returning fire until he defeated an ambush, and then refused to board a medevac helicopter until every other wounded trooper was accounted for. Another specialist tried to remain in the fight even though an AK-47 round had taken off most of his arm. An officer dived into a burning Humvee in a vain effort to rescue a dying friend. Those were the stories of our deployment. Those were the men I knew.

When I came home, I was racked with grief. All the emotions that I’d put aside because of the life-and-death necessities of the job came flooding back. But that wasn’t the end of my Army journey. It was the beginning. I spent six more years in the reserves, a span of time that took me from Iraq to weeks in a bunker in South Korea and to a short assignment on the best Army base in the world, Caserma Ederle in Vincenza, Italy.

Throughout my service, I experienced a paradox: I felt both unimportant and alive with purpose. From the first minute on the helicopter flying into my base, I realized that I was a very small cog in a very big machine. I was expendable. But I also felt an overpowering sense of duty. I prayed a simple prayer, asking God to give me the wisdom and courage to do my job well, whatever my job might entail.

There are powerful reasons that the overwhelming majority of veterans feel proud of their service. Even the post-9/11 generation—the men and women who fought the frustrating “forever wars”—not only feel proud of their service; they endorse joining the military. This is true even when they suffered emotionally traumatic experiences during their own deployments.

And that takes me back to March 2008, when our fallen brothers were airlifted home. Two helicopters landed at our base. They turned off their engines. In complete silence we stood as Torre, Albert, Donald, and Phillip were loaded on board to begin their long journey home.

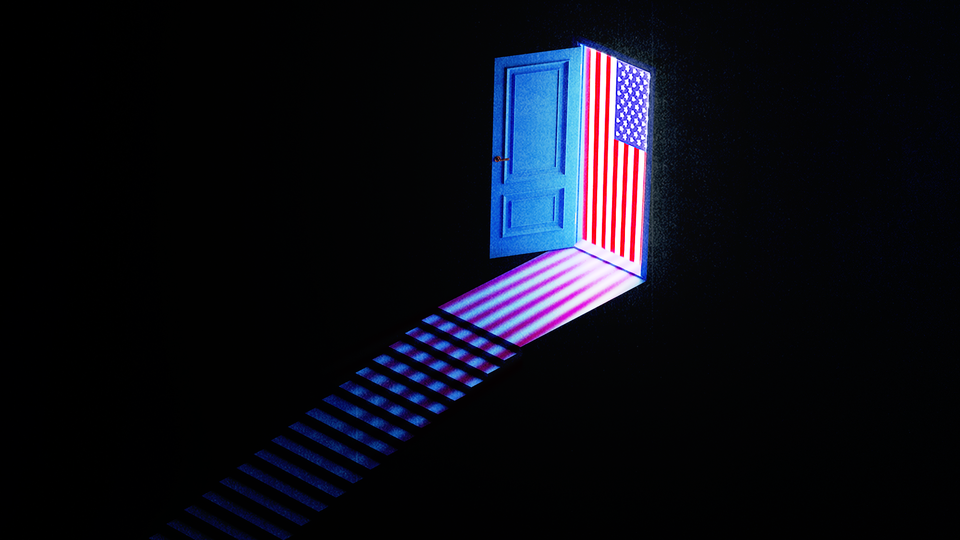

In that instant, holding my salute, I had a distinct feeling—one shared by veterans from across the span of our nation’s history: This is where I’m supposed to be. Most people don’t serve, and that’s fine. It’s good, even. We don’t want a thoroughly militarized country. But some people must, and when they choose to serve, they’re not investing in a president or a policy but in the nation itself.

The decision to serve is a tangible declaration that you love your home—the place and its people—enough to bear profound burdens to sustain its existence and its way of life.

Memorial Day is the day set aside to remember our fallen brothers. Veterans Day is a day dedicated to the living, the people who stood at attention, honored the lost, absorbed their grief, and then did their job, day after day, month after month, year after year.

When I was a younger man, I’d see the older vets wearing hats with their unit insignia, and I’d thank them for their service. But I’d also wonder, Was military service that profound? Was it something that would shape you so much that—decades after it was over—you wanted people to know that it was still part of your identity, still part of who you are?

Now I know. It is that profound. It was the honor of my life.