Sign up for David’s newsletter, The Third Rail, here.

Ever since Donald Trump won the Republican nomination for president in 2016, an industry of rationalization and justification has thrived. The theme is clear: Look what you made us do. The argument is simple: Democratic unfairness and media bias radicalized Republicans to such an extent that they turned to Trump in understandable outrage. Republicans had been bullied, so they turned to a bully of their own.

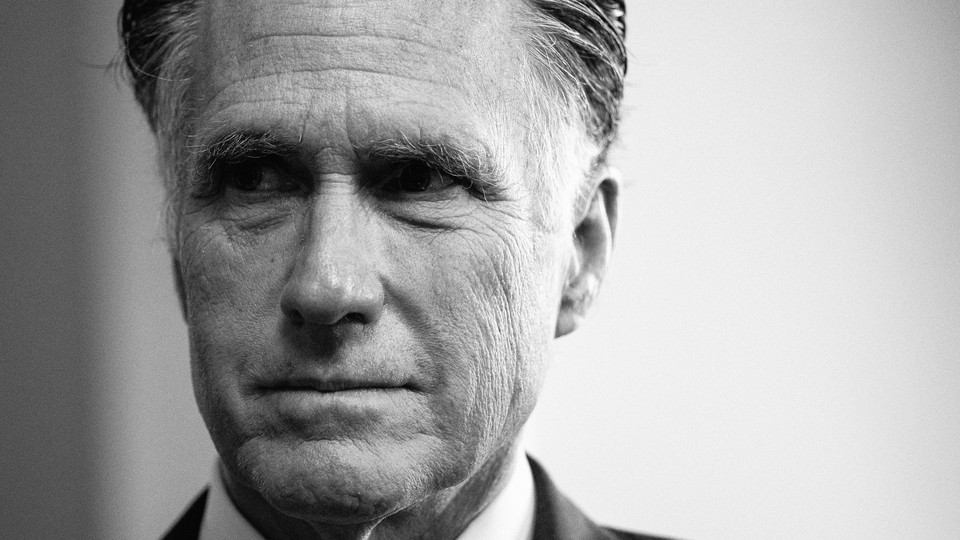

No aspect of that theory has been more enduring than what I’ll call the Mitt Romney martyr thesis. The Republicans nominated a good and decent man—so the argument goes—and the Democrats and the media savaged him. Republicans respected norms, Democrats did not, and now those same Democrats have the gall to savage the GOP for Trump?

I happen to agree that there has been, in fact, a Mitt Romney radicalization process. But it is quite the opposite of what this narrative suggests. It isn’t rooted in Republican anger on behalf of Romney but in Republican anger against Romney, and over time that anger has grown to be not just against Romney the man but also against the values he represents.

The Mitt Romney martyr thesis is important to understand. Like many popular (but mistaken) theories, it’s based on some grains of truth. Many of the attacks against Romney were definitely extreme, most notably when in 2012 Joe Biden told an audience that included hundreds of Black Americans that Romney’s policies would “put you all back in chains.”

Biden wasn’t referring to literal slavery but rather the “chains” of, in his view, unfair economic rules. But the language was indefensibly inflammatory. When Biden launched that attack, I was personally infuriated. I was a Romney partisan from way back. In 2006, just as Romney planned his first run for president, I formed a group—along with my wife, Nancy, and a small band of friends—called “Evangelicals for Mitt.”

Our goal was to persuade evangelical Christians to vote for a Mormon candidate. We built our case around Romney’s competence and character. (It was sadly naive to believe that the bulk of evangelical voters truly cared about personal virtue in politicians.) We spent countless hours supporting Romney through two separate campaigns, and in 2012 Nancy and I both were Romney delegates to the Republican National Convention.

A partisan mindset is a dangerous thing. It can make you keenly aware of every unfair critique from the other side and oblivious to your own side’s misdeeds. I was indignant about attacks against Romney, for example, while brushing off years of birther conspiracies against President Barack Obama as “fringe” or “irrelevant.”

Then, of course, Republicans nominated Trump, the birther in chief, and the scales fell from my partisan eyes.

And now, in hindsight, the real Romney radicalization is far more clear. You could see the seeds planted during the 2012 Republican primary. On January 19, two days before South Carolina primary voters cast their ballot, Newt Gingrich had a moment during the GOP primary debate.

The CNN host John King asked Gingrich about claims by one of his ex-wives (Gingrich has been married three times) that he pressed her in 1999 to have an open marriage. Gingrich responded by condemning the “destructive, vicious, negative nature of much of the news media,” declared that he was “appalled” that King would begin a presidential debate on the topic, and said that it was “despicable” for King to make Gingrich’s ex-wife’s claim an issue two days before a Republican primary.

The crowd interrupted Gingrich with cheers and hoots of approval. But why? Wasn’t King’s underlying question fair? After all, Gingrich had admitted to cheating on his first and second wives, and he admitted to cheating on his second wife at the same time that he was speaker of the House and leading impeachment proceedings against President Bill Clinton for lying under oath about his own extramarital affair.

Moreover, Gingrich was having his affair after the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in America and a key Republican constituency, had passed a Resolution on Moral Character of Public Officials that contained the following statement: “Tolerance of serious wrong by leaders sears the conscience of the culture, spawns unrestrained immorality and lawlessness in the society, and surely results in God’s judgment.”

Surely, heavily evangelical voters in a key Republican stronghold would be concerned about Gingrich’s scandals? No, they were far angrier at media outlets than they were at any Republican hypocrisy.

Gingrich went on to win the South Carolina primary in a “landslide” powered by evangelicals. It was the only time in primary history that South Carolina voters failed to vote for the eventual GOP nominee. But South Carolina voters weren’t out of step; rather they were ahead of their time. They forecast the Republican break with character in favor of a man who would “fight.”

To understand the emotional and psychological aftermath of Romney’s loss, one has to look at the cultural break between the GOP establishment—which commissioned an “autopsy” of the party in 2012 that called for greater efforts at inclusion—and a grassroots base that was convinced that it had been hoodwinked by party leaders into supporting the “safe” candidate.

They wanted a street brawler, and when (they believed) Romney campaigned with one hand tied behind his back, they were angry. Yes, there was anger at Democrats and reporters for their treatment of Romney, but the raw anger that really mattered was their anger at Romney for the way he treated Obama and the press. They were furious that he didn’t angrily confront Candy Crowley when she famously fact-checked him in the midst of the third and final presidential debate of 2012.

And so the Republican establishment and the Republican base moved apart, with one side completely convinced that Romney lost because he was perhaps, if anything, too harsh (especially when it came to immigration) and the other convinced that he lost because he was too soft.

Trump’s nomination was a triumph of that base. Well before Romney came out against Trump in the primary and well before Romney’s first impeachment vote, Trump supporters scorned him. They despised his alleged weakness.

When Trump won, the base had its proof of concept. Fighting worked, and not even Trump’s loss—along with the loss of the House and the Senate in four short years—has truly disrupted that conclusion. And why would it? Many millions still don’t believe he lost.

The Mitt Romney martyr theory thus suffers from a fatal defect. It presumes that large numbers of Republicans weren’t radicalized before Romney’s rough treatment. In truth, they already hated Democrats and the media, and when Romney lost, their message to the Republican establishment in 2016 was just as clear as it was in South Carolina in 2012. No more nice guys. The “character” that mattered was a commitment to punching the left right in the mouth.