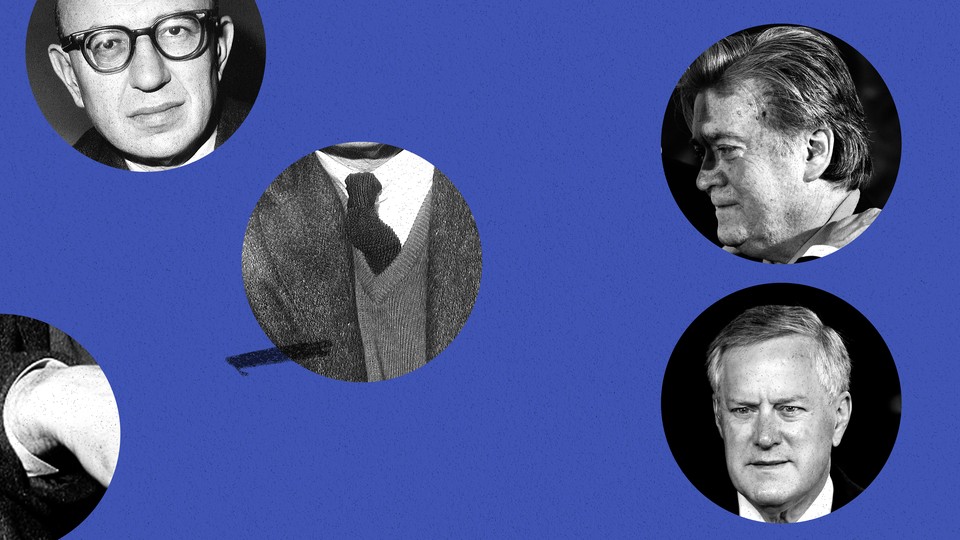

The Trump Enablers Truly in Contempt of Congress

Unlike those involved in the January 6 coup attempt who refuse to testify, my communist grandfather respected democracy and had the courage to turn up, say his piece, and take the consequences.

Over the weekend we learned that Donald Trump’s former political strategist Steve Bannon had written to the January 6 committee indicating that he might, after all, be willing to testify. Bannon, who has been indicted for contempt of Congress, had previously claimed to be bound by executive privilege—though no court has accepted that argument—but he now presented a letter from the former president granting a waiver. Indicating perhaps how seriously he took the committee’s work, Bannon chose to participate in a podcast with Trump’s former lawyer Rudy Giuliani rather than appear at a court hearing yesterday on the contempt charge.

“Congress should not fall for the Bannon-Trump ploy of the withdrawal of a nonexistent privilege,” Norm Eisen, a former ambassador to the Czech Republic and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me. “Compliance does not purge criminal contempt as a matter of law, and Bannon should not be shown any leniency unless he tells the whole truth.”

What of other Trump associates who have refused to obey the committee’s subpoenas and testify? Only the former trade adviser Peter Navarro faces charges and risks the mandatory minimum of a month in prison if found guilty. The Department of Justice has declined to follow up on the committee’s other referrals—most notably, of Mark Meadows, Trump’s former chief of staff. Why this hesitancy to prosecute contempt of Congress?

One explanation may go back to what has come to be seen as one of the darkest episodes in congressional history, which involved my own grandfather: the hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee. HUAC was established in the late 1930s to investigate subversive political activity—ostensibly, at first, of both the fascist and communist varieties. By the late ’40s, however, with the Cold War under way, the committee was focused almost exclusively on unmasking alleged communist plots. Through the ’50s, HUAC’s work ran in parallel to Joseph McCarthy’s Senate hearings, which promoted Red Scare paranoia.

My grandfather, the author Howard Fast, came to HUAC’s attention through his work for the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, a group set up in 1941 to fund care for refugees from Franco after the Spanish Civil War. The organization had a fundraising arm called the Spanish Refugee Appeal, which my grandfather learned about, he told me, from a friend, the playwright Lillian Hellman, who was the partner of Dashiell Hammett. My grandfather was then working in Hollywood, after a wartime stint at the Voice of America. (According to family lore, Hammett also had an affair with my grandmother, Bette Fast.)

Others involved in the refugee appeal included Orson Welles, Dorothy Parker, Dalton Trumbo, Leonard Bernstein, and Langston Hughes; the group held parties and dinners in Hollywood to raise money for civil-war orphans. But to the Red Scare witch hunters, the refugee committee was a communist front organization. Some of those involved were communists—my grandfather, certainly—but by no means all. In April 1946, a year or so before HUAC went after the Hollywood Ten, the House voted to refer the refugee committee’s board, my grandfather included, for criminal prosecution for refusing to cooperate with HUAC.

Action from the Justice Department was swift. According to The New York Times, “All of them were held in contempt,” and most were jailed, some for as long as a year (my grandfather served three months in federal prison). My grandfather later also appeared before McCarthy’s Senate subcommittee, and as he wrote: “Each time I called upon the protection of the Fifth Amendment … I demanded from the Senators the right to state why I was using this privilege. They were almost hysterical in their unwillingness to grant me that right. The hearing was being televised, and they had no desire to allow an explanation of the beginnings of the Fifth Amendment to go out over the air to millions of Americans.”

Jail and blacklisting ruined many lives, though not, fortunately, my grandfather’s. He began writing Spartacus in prison and found a way to self-publish the book during the blacklist under a pseudonym. It came out via an imprint that he and my grandmother scraped together their savings to create, which they named the Blue Heron Press—after thinking better of naming it the Red Herring Press.

My grandfather saved his explanation for taking the Fifth that the senators wouldn’t hear for his 1990 memoir, Being Red: “Some of the best and richest parts of our heritage exist because the early dissenters were willing to fight for principles, face prison, and if necessary, death. Unless we realize that this is also the case with the dissenters of today, we will find that we have sold our entire democratic heritage for a mess of very poor pottage.”

The congressional power to subpoena witnesses and punish those who refuse to comply needs to be used carefully, and the prosecutions of those who defied HUAC and McCarthy are viewed by many as a gross overreach that infringed upon citizens’ constitutional rights. But there is a sharp difference between then and now. Whereas my grandfather was jailed for refusing to divulge details of charitable work for orphans—because anything anti-fascist was seen as suspect—Steve Bannon was indicted for refusing to share what he knew of an actual fascist plot against America. Bannon has offered no defense of our “democratic heritage,” but has instead hidden behind the former president’s dubious assertion of executive privilege. Now Bannon appears to be seeking to trade belated cooperation to get the earlier charge of contempt dropped.

“Unlike your grandfather, who showed up, actually appeared before Congress, and asserted constitutional and other privileges on a principled basis, Bannon failed to show at all and is utterly unscrupulous,” Eisen said. “He should be prosecuted, and a jury will convict him.”

The part Congress played in the witch hunts of the ’40s and ’50s deserves the infamy it has attracted down the years. But that is no excuse for the Department of Justice to soft-pedal action against those who prefer to protect their political boss rather than the Constitution. Mark Meadows was the chief of staff for the most powerful man in the world, a president who was trying to overturn the result of a democratic election in order to stay in office illegally and illegitimately. Those who advised, aided, and abetted the former president in the run-up to January 6 but refuse to testify should definitely be held in contempt.