‘Ultimately the Story Will Have Its Own Say’: A Conversation With Morgan Talty

“If you want a reader to follow you to the darkest places, you have to make them laugh too.”

Previously in my author conversation series: Christopher Soto, R. Eric Thomas, Jasmine Guillory, Alejandro Varela, Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Megha Majumdar, Ada Limón, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, Crystal Hana Kim and R. O. Kwon, Lydia Kiesling, and Bryan Washington.

*

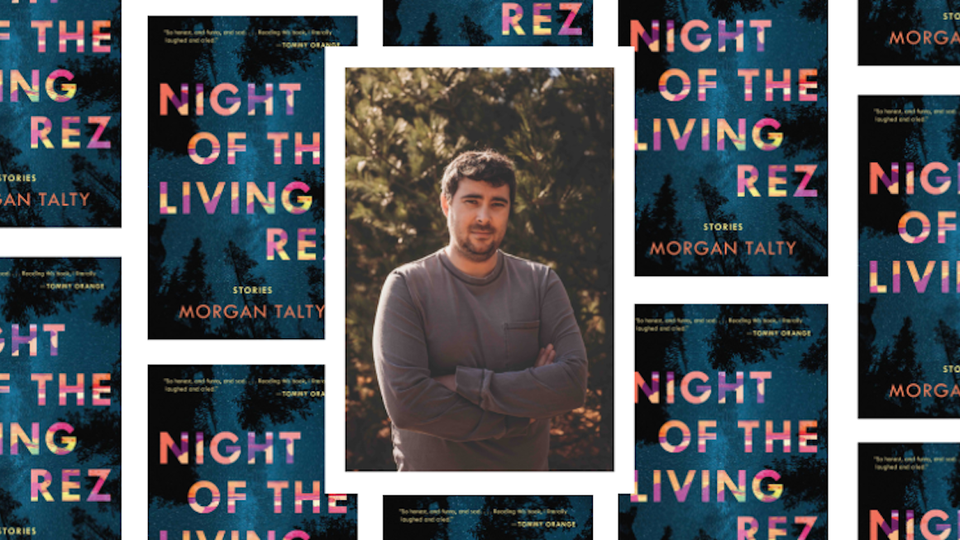

When Morgan Talty, author of Night of the Living Rez: Stories, began sending a draft of the book to prospective agents, many wanted to know if he had a novel to share instead. “Story collections are hard to sell,” Talty told me. Following its publication by Tin House earlier this year, Talty’s debut book has far exceeded his initial hopes or expectations: It won the New England Book Award for Fiction, was shortlisted for the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize, and is now one of three finalists for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

For Talty, whose earliest writing grew out of a love for oral storytelling, the focus is always on the characters—on understanding their relationships, their messy love for one another, their deepest desires. “These characters [in Night of the Living Rez] felt connected to the people I know,” he said. “And so I wanted to do them as much justice as I would if they were here with me, in my life.”

A citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, Talty is an assistant professor of English at the University of Maine at Orono; on faculty at the Stonecoast MFA-in-creative-writing program and the Institute of American Indian Arts; and a prose editor at The Massachusetts Review—all collaborative work that, he says, “charges [his] batteries” and nourishes his own writing. Last month, we spoke about his debut publication experience, the novel he’s working on, his ideal writing routine, and how determined he is to avoid storytelling that is “performative for a white readership.”

*

Nicole Chung: When and why did you first start writing?

Morgan Talty: I always loved telling stories orally and found a lot of joy in that. For many reasons, including home life, I wasn’t the best student growing up. It wasn’t until college that there was space for me to fall in love with written literature. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. I suppose it was a process of elimination—finally I was left thinking, Either I win the lottery, or I write. I went to Eastern Maine Community College after high school and met a teacher, John Goldfine, who told me I was a good writer—I didn’t believe him for a long time—and it was there that I first started writing, at 18 and 19. It was a way to do something I’d loved my entire life, which was telling stories.

Chung: The linked story collection is one of my favorite forms as a reader; there are so many ways into the book. How did this collection come together? Did you set out to write a linked collection, or did it come together more organically?

Talty: In 2015, while I was at Dartmouth, I wrote a short story called “Night of the Living Rez.” That ultimately became the title story of this book, though it was a very premature version. I graduated in 2016 and started a low-residency MFA program in 2017. By then I had a couple of other stories from David’s point of view, and so when I was thinking about what to work on in the program, I decided to try to write a story collection. I already had this David character as a young adult, so I thought I would write more stories about him that could be read in any order. I wrote 15 stories, winnowed it down to 10, and the book was just … really bad. It wasn’t working, even though some of the stories were working. It was the same character in different situations, and I found myself thinking what any reader would: What is the point? I put the project aside, thinking it was a book that failed and I would do something else.

I’d heard this story about a guy getting his hair frozen in the snow, and so I decided to write that story. It ultimately became “Burn.” I thought, Okay, this first-person narrator isn’t David; I’m doing something completely different. But as I was writing, I got to the line where Fellis says to Dee, “Get me out, Dee.” I knew I needed to say the character’s name there, but I had no idea who he was. I put the letter D in as a placeholder. Time went on; I’m revising; the story is done except for this character’s name—finally I was like, What if his name is Dee? Whatever resistance I had released itself, and I thought, Wait, is this David all grown up? It is!

That whole project I’d shelved came back to life, and I started exploring these Dee and Fellis stories. Now there was a central question that went through the book: What happened to David? I wrote what I wanted while also paying attention to what the stories wanted. It’s out of our control sometimes—we can try to do what we want, but ultimately the story will have its own say.

Chung: In one piece I read, you said that the way your family coped with trauma was to laugh at it. I related to that very much. Can you talk more about how you bring humor into these stories that also carry so much grief?

Talty: If you want a reader to follow you to the darkest places, you have to make them laugh too. It’s hard, because humor is the most subjective element—you don’t know what someone is going to find funny, you know?—but I think all of us have had these horrible moments in life that kind of make us crack, and then we find that we’re laughing.

Chung: I think the dark humor added so much to the characterization, and the way you write about the complexity of loving other people in hard, messy ways. What else helped you see these characters and hold your interest as a writer?

Talty: Before I came to fiction, I wrote memoir, nonfiction, about family, about friends. I wrote about the same things this book deals with—how do we love the difficult people in our lives?—and often found myself thinking, It would be cool if this had happened instead, and that was how I moved into autofiction and then pure fiction. The characters of Mom and Paige are like the shadows of my mom and my sister that I wrote about years ago. My mom always told me that she thought about naming me David at one point, so when I switched to fiction, I decided to name this character David.

What really held my attention is that these characters felt connected to the people I know. It’s not autobiographical, but I had to write about these people in the way I would have written about real people. Fictional characters are real; they become real memories and experiences for us. And so I wanted to do them as much justice as I would if they were here with me, in my life.

Chung: One of the things you hear is that it’s tough to debut with a short-story collection. Like most publishing rumors, I have no idea how true that still is. But I feel like no matter what kind of writer you are, the transition from “I have this book” to “I have to sell this book” can be so jarring. Only if you want to talk about it, what has your debut publication experience been like so far?

Talty: I love talking about this. I queried a lot of agents, and they were always like, “I don’t know how to sell this”—which was a way of saying, I think, “I don’t think anybody will buy this”—or they’d say, “Tell me about your novel.” Story collections rarely sell more than 5,000 copies, which is a low number, and that’s not necessarily a reader’s fault. I think we have prioritized novels over short fiction. But I feel like we might be moving away from that a bit now, maybe because our attention patterns and the way we read has changed.

A friend eventually introduced me to my current agent, Rebecca Friedman, and she read the book and immediately said “I can sell this.” She sent it out to big publishers, as well as to Masie Cochran at Tin House, and within two weeks Masie said “I want this.” We could have kept at it, trying to sell it to a bigger house for a larger advance, but I talked to Masie and we just fit really well—she was looking at the book in the same way I was. Now that the book is out, I feel like it’s representative of so many story collections that could do well, but publishers don’t want to take the risk.

Chung: Right, and yet every book is a risk to some degree! I’m glad you have so much support from your publisher. I’m such a fan of Tin House; they’ve published some of my favorite books in recent years.

For what it’s worth, I had almost the same experience with my first book, which was also published by an indie press. When I talked to my editor, Julie Buntin, I knew I would never find anyone who was more committed to or excited about it. That enthusiasm and how much your team believes in your book is so crucial, though obviously there are never any guarantees when you publish. My debut was kind of a hard sell, too, and then I was shocked by everything that happened afterward.

Talty: That’s so true, what you say about support from your team—not just in terms of editing and vision but also promotion and what they’re going to put behind it. I will say that I was completely shocked too. I was talking with my wife about this recently—we thought this book would be a stepping stone to the next book, which was something we’d come to terms with. I knew, going in, how story collections often sell; I’d heard the numbers. And then I started to get enthusiastic blurbs from Tommy Orange and Terese Marie Mailhot and Laura van den Berg and Jim Shepard. It was not until a couple of weeks after the book was published that I was like, wow, this is exceeding any expectations I would have had. I never expected the book would win awards or be a finalist for others. I just hoped it would be published and have an impact on some readers.

Chung: I appreciated the way you incorporated traditional stories in Night of the Living Rez—it felt like an invitation to think about what storytelling is, the power it has. And you do this in another way by introducing the documentary crew that shows up to film life on the island; though it’s not the focus of the story, it made me reflect on who often gets to tell stories, what sorts of images get promoted over and over, the power those images can have. You make space for readers to think about all of these things critically.

Talty: I was so careful with this book, about not making it performative for a white readership. When it came to storytelling and these stories within stories, I thought a lot about that. I am deeply committed to character, and so I wanted to put that first, put human emotion first, and then build on that. Who are these characters, what do they want, what will they do to get it, what are their relationships?

When it came to the cultural elements, I never sought to dangle it there for the reader as a kind of token. Every place where the Penobscot language was used, it was where it felt natural to me, where I or someone I knew would say something like that. With the creation stories and myths, I looked for moments where a character might actually think about them. I was so fascinated that the documentary crew were there. They don’t know what’s going on; they don’t understand—they see reactions to traumatic events, but they never get the actual story. The story stays within the family, within the community.

Chung: I will often find myself talking with fellow writers about this—how to tell the stories we want to tell, put certain things in the center of the page, in ways that don’t feel performative, as you say. I never want to inadvertently write something that caters to the white gaze. You want to write stories anyone can read, and you have, but in your book, your characters never spend time explaining who they are, or explaining their community.

Talty: Exactly. That’s something I really wanted to avoid. Everybody can Google! That’s the shitty part about being a marginalized writer—it’s expected that you will need to explain for a white readership. A lot of literature does that.

Chung: It does. For a long time, that’s what got published. But I really appreciate that there’s been pushback from marginalized writers saying no, we’re not going to do that.

I read that you’re working on a novel. Does your process change at all depending on whether you’re working on short fiction versus a longer, more sustained project?

Talty: I feel like short stories are easier for me to get right. It usually takes me five to seven days to draft a short story. With the novel I’m working on, I wrote the first draft, and then I scrapped it and rewrote the whole thing. It probably took around four months, working on it every day for one to three hours, to finish the second draft.

When it comes to routine, my ideal situation is to write before anybody else is awake and I’ve not yet been reminded of the harsh realities of the world, you know? I’ve always been a morning person. I prefer there to be noise, like a dryer going or something—sometimes I’ll put headphones in and listen to a dryer running for hours on YouTube if I don’t have laundry to do. I get up and pace a lot, because I like to trick my brain into thinking I’m not near my computer. When I have a draft, I go back and forth between a hard copy and the computer. I like to lay it out on the floor and look at it; it helps me get ideas when I’m revising.

Chung: You’re also a professor and an editor. How does this work interact with your writing?

Talty: I find that mentoring and editing and working with other writers is rejuvenating for me. I have to do it. It charges my batteries for the creative work. I’m very reclusive when it comes to my own writing—I don’t have a writing group—but I need editing and teaching and that literary community.