How Lydia Kiesling Fled to Write Her Next Book

“It’s absolutely breathtaking how quickly you can go from ‘This is not possible’ to ‘I might actually be almost done.’”

Welcome to I Have Notes, a newsletter featuring essays, advice, writing and craft discussions, and more. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. Past editions include How Do I Talk to My Daughter About Violence Against Asian Women?, You Do Not Always Have to Say Yes, When Other People Don’t See Your Creative Career as “Work,” and Talking About Care and Craft With Bryan Washington.

This is a free edition, but Atlantic subscribers get access to all posts. To support my work and gain access to my full newsletter archive, subscribe to The Atlantic here.

*

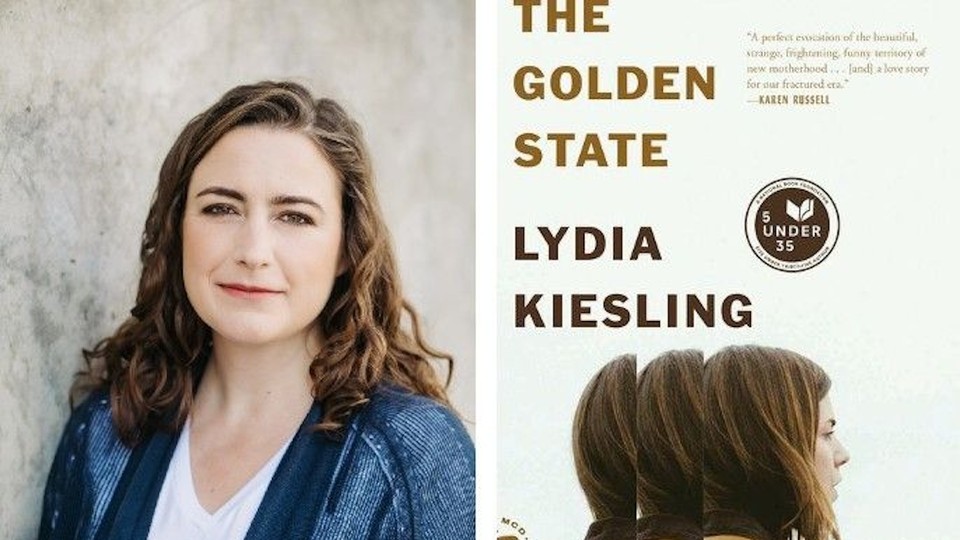

I first met Lydia Kiesling, author of The Golden State and a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree, at the Portland Book Festival in November 2018. We were two ships passing, headed to different panels, but that didn’t stop me from running across the parking garage to give her a hug. The year before, we had both found ourselves in a small (virtual) pod of women writers; all of us were publishing our first books in the summer and fall of 2018. Our group was an invaluable source of information and support—there was always someone to vent to, celebrate with, or ask for a gut check, and the entire publication process was made less terrifying and more fun because we were all going through it together.

By the time I met Lydia at the festival, we had been cheering each other on and trading advice for over a year, so our chance run-in was also a meeting between friends. I’m so glad that I have been able to keep in touch with her and follow all her brilliant work since then. A few weeks ago, she spoke with me over Zoom about her approach to freelancing versus fiction, the challenges of writing while parenting through the pandemic, why she relies on her creative community, and how she literally fled her home to finish a draft of her next book.

Nicole Chung: Lydia, thank you for taking the time to talk to me. I know this is one of the worst questions, but how has writing been going for you?

Lydia Kiesling: I actually finished a draft of my second book recently! I started in 2017 but didn’t get going on it in earnest until 2019, and really got into the swing of it just before the pandemic started and everything came to a halt, when I was about halfway through.

In spring 2020, if you had told me that the draft would be done by now, I wouldn’t have believed you—it just felt impossible. I had between two and three kids in my house all day every day for a lot of the pandemic (I only have two kids, but last year another friend came over every day for remote kindergarten with my older child, which I administered). I’m very lucky that I have a flexible freelance schedule and could accommodate the massive disruption wrought by the pandemic, but I wasn’t really able to work for a long time. I picked up some freelance work when I could, and prioritized that when I had any at-home work time.

Then at a certain point I was like, Well, I did put a lot of work into this book, and I want to work on it again. So I thought about what would make that feel possible. Around August of Pandemic Year One, I just fled—I told my husband, “I’m sorry, I’ve gotta go,” found an $80-a-night cabin 45 minutes away, and went there for three nights. Over two years, I think I did that four times, between one and four nights at a time. There is a lot of privilege built into this—having another parent who could take over for a few days, having the money to spend.

Chung: So you didn’t work on the novel at home, it was all written elsewhere?

Kiesling: Pretty much, although I did start to get into a daily routine again last spring, when the kindergartner started hybrid school and was in a building two hours a day, four days a week. But life and paid work intervened pretty quickly even then.

I’ve sort of fallen in love with the fleeing method, although I do sometimes think, Is this really how I want to run my creative life, only working on books when I leave my family? Both kids have been in full-time in-person school since September, but I still went away in January for a few days to work on the book. It feels like maybe that’s how I do this now.

I’ve stayed in these cabins that have all had either a composting toilet or a porta-potty. It’s a very indoor/outdoor experience, but it’s heaven—I’m a complete monster when I’m there; I eat a bag of chips and weird prepackaged sandwiches from the grocery store or cold boxes of Popeyes for meals; I work when I want to, drink a fair amount of wine, and watch my terrible shows when I need a break. It is a kind of paradise.

Chung: I could not love this more. What was the first book-writing experience like, then, by comparison?

Kiesling: I wrote The Golden State over the course of a year—I had a very rigid timeline because I had quit my full-time job and taken a part-time editing job at The Millions. The idea was that I’d edit for about two hours a day, and then work on this book the rest of the time. Again, I will note it was a privilege that was possible because I have a spouse with a full-time job and health insurance. We didn’t have enough money for that to work for a long time, but I had basically a year to figure out whether the book was going to be something. I had a spreadsheet; I was into tracking when and how long I worked on it. There were days when I didn’t work on it, and I felt like a huge failure on those days, although now I know it was okay to do that.

Chung: I’m just doing the math—you must have had a small child at this time?

Kiesling: Yes, I had a toddler who went to day care, and I was 13 weeks pregnant when I sold the first book. It was a very rushed writing process. I had to work on it every day, and so it never would have occurred to me to leave and go somewhere else. Well—that’s not actually true: During that book some friends offered their cabin close to where we lived as a retreat space, and I went twice for a night each, first at the beginning and then at the end of the novel-writing process, and each time it was a disaster. I didn’t have enough confidence in my ability to write fiction; I hadn’t come to see it as the amazing escape and pleasure that I do now (thanks, pandemic!), and I felt so much pressure to produce a huge amount of work that I panicked and got terrible writer’s block. Both times, I wrote nothing—the second time, I actually left and went home almost immediately because I felt so defeated. But now I have another kid, and I know that this kind of peace is paradise whether you work or not.

The pandemic has upended how I think about writing and what is possible. I know there are people who subscribe to the school of thought that if you’re a writer you have to write every day, butt in the chair, and I’m sure for some, that’s true—but I’ve tried both methods, and sometimes it’s just not possible to do that. For logistical reasons, yes, but also for mental reasons. Some days I have my butt in the chair and I still can’t do it. But I know that if I wait until I have that feeling of urgency, I can get it done—especially if I kind of trick myself into thinking that writing is some kind of escape or vacation from my domestic obligations.

Chung: I’m glad you said this, because I will frequently ask myself, What sort of work am I doing today—book, newsletter, freelance?—and I find it hard, sometimes, to jump between tracks on the same day. But then I talk to writers who are like, “No, it’s not healthy to compartmentalize so much”—and I’m like, “Well, what am I supposed to do then?”

Kiesling: Right, and here’s a comparison to the Before Times: Prior to the pandemic, I would always stress about trying to get writing work done during the holidays, when even during “normal” times there was no childcare and lots of obligations and schedule disruptions. But now that I’ve gotten into this pattern of working on my book for a few days every few months, this past holiday season I was like, I’m just not going to worry about writing over the holidays. I did take on freelance assignments that I knew would pay well, and that’s what I prioritized instead of trying to adhere to a punishing book-writing schedule at such a busy time. I don’t want to say that I didn’t think or worry about the book at all over the holidays, because I did, but it was comforting to know that in January I’d be going to a barn and I could work again.

Chung: Speaking of freelance work—I always think of it as a sprint, while a book is a marathon. What makes a freelance assignment exciting and worth it to you? How do you decide what to take on? And how do you fit that into your day-to-day life, because you don’t go to a cabin to work on it?

Kiesling: Freelance work feels like a muscle that’s habitually used, one I can kind of count on—I know that I can sit on my couch or at my dining-room table during the day or at night and make myself work on a freelance assignment, in part because I’m not so precious about my time or the conditions I need to write; whereas I can’t do that with a book, because that still feels new and difficult to me. There was a time when I’d say yes to absolutely every assignment that came my way because it felt necessary, but then you start to do a cost-benefit analysis—every writer I know has done this. Now I ask myself: Is this going to pay well? Does it feel like it’s enough in my wheelhouse that it won’t eat up my whole life and soul, or is it something that isn’t in my wheelhouse but feels like a worthwhile challenge and a way to stretch myself a little bit?

Last year, I took on an assignment for Bon Appétit and it was wonderful; I’m so glad I did it—I knew I’d learn a lot and get paid, so it was worth it. I can’t do that all the time, but it helped me think about how I want to use my time and what sort of freelance work I want to take on. I also like to do volunteer work in our community, and I can’t do that if I’m taking on too much freelance work or just overextending myself. I have realized that sometimes you can say no to something and it’s okay!

Chung: Absolutely—people will understand, and they will not hate you!

Do you feel like you have a writing or creative community, and has it been helpful to you?

Kiesling: I definitely do. I feel so lucky that when my first book was coming out, I was in both real-life/in-person and virtual writing spaces. I got to know a lot of other writers whose books were coming out that same year, and they were so great, as you know.

Chung: Yes! That’s how we met.

Kiesling: It was just so meaningful to be able to connect with all of you. We had an email group for debut authors, and it was so helpful to be able to talk with others going through it and ask, “Is this normal? Should I expect this? Should I say yes to this? Is it weird that I wrote this in an email, or should I go hurl myself into traffic now?”

When I lived in San Francisco, I got to make great writer friends and see them in person, and was sad to leave them when my family moved to Portland. Now I talk with writers who live here and some who live far away. Since the pandemic started, texts and emails have been so important. I get anxious about sharing pages—I’m secretive and weird about that—but I do love to have friends I can text who understand that writing a book is such a weird process that feels so miserable one minute and so joyful the next.

It can be embarrassing to talk about this with people who aren’t writers, even if they’re curious or kind—you just feel like an asshole when you complain about the book you’re writing, because many people have jobs that are much harder than ours, and at the same time it helps to have writer friends who will say, “Oh, no, no one has ever had to do anything worse than work on this book on this day.”

Chung: Right, like you know it’s not the hardest thing anyone’s ever done, and it’s still really damn hard.

Again, I have to say that I’m incredibly impressed by your marathon cabin-based writing—that’s pretty badass. Do you think you’ll do this with future books as well?

Kiesling: I’d like a mix, ideally. You know, when you have a more regular writing schedule and you keep to it for a sustained period of time, you don’t lose stuff. The way I’ve been doing it, it’s like, If something is going to be in this book, it better occur to me in the next three days! I think it would be great to be able to have a regular writing practice, and then when I need to revise or get through a particularly tough chunk of the book, maybe I could go somewhere for a few days or, when my kids are older, a few weeks.

Chung: What’s your revision process like?

Kiesling: At first I don’t read anything over, I just have to produce it. Once there’s a critical mass, a real trajectory, then I pay like $25 to have the book printed and spiral-bound so it feels more official, and I read through it. I will actually cut out sections and lay them on the floor, like the Little Women montage—I like to see if things could go in a different order. With this next book, I think I did three print-and-binds, and went through it that way. It helps me see what’s there.

Chung: I love that. I probably wait too long to print and read and mark up physical pages. Last question: What do you know now that you wish you’d known starting out?

Kiesling: For freelance work, I tell everyone this: You really don’t have to wait for an invitation to pitch. Yes, there are many gatekeepers and structural barriers and it can feel forbidding, but it’s astonishing how much of a person’s writing career can be based on “I wanted to do this and I wrote to someone.” You can just go for it.

In terms of book writing, I’ll say that it’s absolutely breathtaking how quickly you can go from This is not possible to I might actually be almost done. Feeling despair, like you’re not only wasting your life but fucking up your family and ruining everything else, is a very real feeling, and it’s okay—but just know that it can change so fast. Not to be a butt-in-the-chair person, but probably the best way to get through is to keep going, even if you’re just keeping the book in your mind or reading some other book for research. Often you can get through it if you don’t give up on the enterprise as a whole. That happened with my first book, and it just happened with this one. I had to trust the process.

*

Thanks so much for reading. If you enjoyed this or any of my newsletters, please consider sharing the sign-up link with a friend. You are always welcome to send any thoughts or questions to ihavenotes@theatlantic.com.