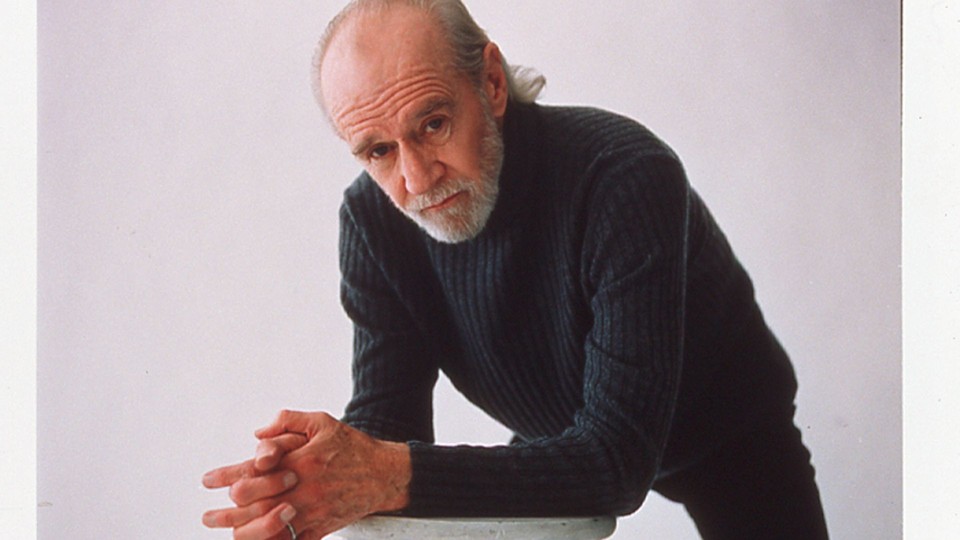

Why George Carlin Is (Still) the Voice of a Disillusioned America

‘George Carlin’s American Dream’ is as angry as I am.

I am not a patriot. I say that as a matter of fact—I am not proud or ashamed of it, but have simply come to accept that I don’t meet the definition. I do not defend America against detractors of our culture. I do not believe in American exceptionalism or the promise of the American dream. At times I have regretted my service in the Peace Corps and the arrogance of having once assumed that I had anything to offer another country at all.

My heroes are not patriots. I have little faith in the resilience or morality of our institutions. I vote reliably but not optimistically. I do not trust or admire the police. I do not believe veterans are inherently heroes. After graduating with a master’s in public administration and passing the Foreign Service exam, I considered running for political office—but eventually I learned that I lack the prerequisite qualification of being a patriot, or being willing to pretend to be one.

My favorite quotes are not patriotic. I do not believe that we are a shining city on a hill. I do not believe that we stand for liberty and justice for all, or that America wants such things. I do not believe that there is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America, or that the arc of the universe is long and bends toward justice.

The events of this month, combined with a prescient documentary, stirred up the kind of anger, frustration, and sadness that I generally have to suppress to live any semblance of a normal life. You already know about the events. The documentary is the two-part George Carlin’s American Dream on HBO Max. And it’s worth your time, if only to watch someone reflect the contempt you may feel, in a way that few social commentators can.

The first part of American Dream follows the early stages of Carlin’s career as a radio DJ and comedian. He started as a “clean” comic whose schtick included fast-talking bits and quirky vocalizations. Being family-friendly didn’t reflect who Carlin was on the inside, but much of his work in those years was a means to an end: He wanted to go into movies and charted a path for himself by adopting the only kind of comedy that had a large audience at the time. The trajectory of his career, which started in the 1950s, doubles as a history of comedy in America. It also reminds us of a Carlin that many forgot or, like me, hardly knew.

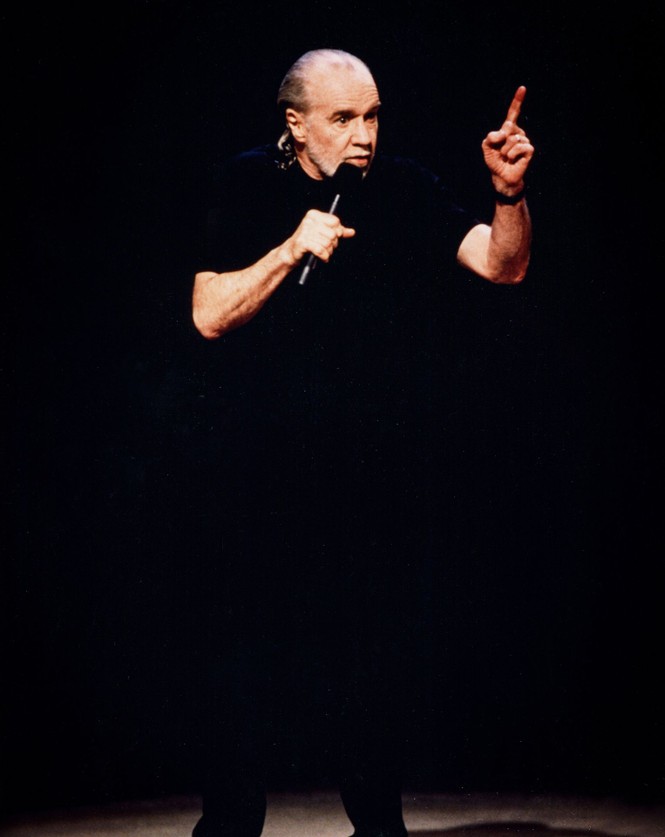

Decades of reinvention would follow. At the start of American Dream Part 2, Carlin is at a low point in his career, widely considered to be a has-been. And then he gets angry.

Comedian Patton Oswalt, one of the documentary’s interviewees, best captures what Carlin faced in those years that he risked becoming obsolete. “Comedy is about the present and the now,” Oswat said. “And then life changes and you hopefully, as a comedian, change and evolve with it. But if you solidify and calcify and go, ‘This is as far as I’m going to go, and dammit I’m still going to say these words,’ then you’re not engaging with the world anymore. You’re engaging with a certain moment in time that you have decided to live in forever. And George ran that risk for a while in the ’80s of becoming irrelevant.”

But Carlin’s career fully swung back: His angry rants are as influential today as ever. He had evolved from a goofy comic and counterculture stoner to someone who vented his frustrations on social and political issues. By choosing to talk about the issues that mattered to him—along with kicking the cocaine habit that had plagued much of his career—Carlin was finally being himself: a person who was deeply empathetic and dismayed by how Americans treat each other.

But despite being known as kind and affectionate offstage, his stage act was pure fury against abuses of power. Carlin bits were the stand-up-comedy version of Rage Against the Machine, particularly for later fans like me (I discovered him in college when YouTube started to take off).

“The reason I believe in blunt, almost violent presentation of my ideas these days is because what is happening to everyone, it is not gentle,” Carlin says in American Dream. “It is not subtle. It is direct, hard, and violent, what’s happening to the lives of people.”

His dissatisfaction with the human condition led to a descent into hopelessness that overshadows some of his later work, when he praised tragedy, natural disasters, and death. But his ability to give voice to political anger and disillusionment still speaks to the part of me that is angry and unpatriotic, and accepts my perception of our country with a cold detachment.

The past several years—this month in particular—I’ve been reminded of Carlin’s “The Secret News.”

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, it's time for the Secret News.

Shhhhh. Here is the Secret News:

All people are afraid.

No one knows what they're doing.

Everything is getting worse.

Some people deserve to die.

Your money is worthless.

No one is properly dressed.

At least one of your children will disappoint you.

The system is rigged.

Your house will never be completely clean.

All teachers are incompetent.

There are people who really dislike you.

Nothing is as good as it seems.

Things don't last.

No one is paying attention.

The country is dying.

God doesn't care.

Shhhhh.

I take a strange comfort in missives like those, if only for acknowledging the kinds of depressing thoughts that we’re generally taught to suppress. But the feeling that my country is hopeless is worth truly feeling when it arrives. America can be hopeless, and the best that many of us can do is to try not to let it swallow us, and try not to be hopeless alone. And then hopefully, when it passes, we can do what little we can to help improve lives.

***

After two years of avoiding it, I had COVID last week, which is why Humans Being wasn’t in your inbox on Saturday. I’m back in action though, and just in time: Next week I’ll be at Greenlight Bookstore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn at 7:30 p.m. to discuss my book, Piccolo Is Black: A Memoir of Race, Religion, and Pop Culture. I’ll be in conversation with the wonderful Laura Bassett, editor in chief of Jezebel, and tickets are free and available here. I hope to see you!

Thanks to everyone for the heart-emoji responses to last week’s essay about Rothaniel. I’ll catch up on my inbox soon-ish, but always feel free to reach out even if you don’t get a response right away. I read them all.

This week’s book giveaway is a hardcover of What the Eyes Don’t See: A Story of Crisis, Resistance, and Hope in an American City, by Mona Hanna-Attisha. It’s about the Flint water crisis and the doctors, researchers, friends, and community leaders who stood up to power. Just send me an email telling me whether you consider yourself patriotic or not, and I’ll send the book to a random person who hits my inbox. You can reach me at humansbeing@theatlantic.com, or find me on Twitter at @JordanMCalhoun.