Kanye, ‘jeen-yuhs,’ and My Graveyard of Heroes

The new Netflix documentary “jeen-yuhs” feels like a celebration, and a funeral.

This is a free edition of Humans Being, a subscriber-only column that searches for lessons in the most popular movies, books, TV shows, and more. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. For full access to future subscriber-only exclusives, subscribe to The Atlantic.

I remember where I was the first time I listened to Kanye West’s debut album, The College Dropout. It was 2004 and I had just begun college myself, and the combination of youth, newfound freedom, and the midwestern summer weather tattooed that moment in my memory. I had just graduated from a Seventh-day Adventist boarding school and escaped an even worse situation back home (you can find some of that story in Humans Being, or read all of it in my memoir) and listening to The College Dropout was pure joy. It felt magical that something so good could exist, and that I was free to play it as much as I wanted.

So I listened to The College Dropout. A lot. I played it until I memorized the track order. I bumped it in my headphones, car, and dorm until I knew each verse and ad lib. That album was liberation music, like my personal freedom songs with Kanye as my savior.

But when I learned of the three-part documentary series jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy coming to Netflix, I wanted to ignore it. In the past few years, Kanye’s never-ending buffoonery includes saying that being enslaved was “a choice,” criticizing Harriet Tubman in a failed presidential run, and publicly harassing his ex-partner and others. I could say that I “dislike” what Kanye has become; I could cite his mental-health struggles, or his mother’s passing, or the cost of being a misunderstood “genius.” I wish I were that understanding. I wish I were above having a strong emotional reaction to any celebrity.

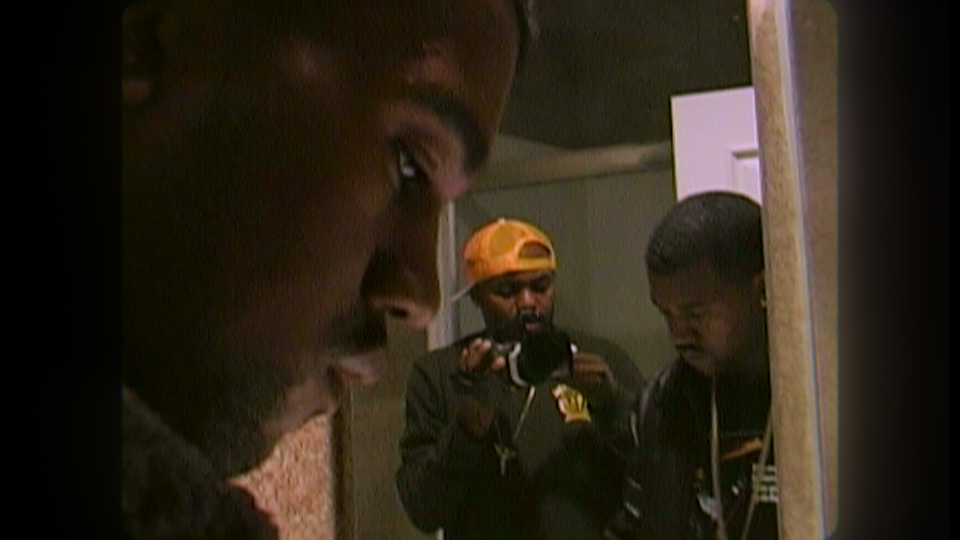

But as I watched jeen-yuhs, which premiered this week on Netflix, my heart felt like it did in 2004. The documentary has over two decades of footage from Kanye West’s life, most notably, so far, from his early-career struggles that would lead to the day that I listened to The College Dropout' in sheer bliss. jeen-yuhs gave me chills more than once.

There’s one scene in a car where Kanye plays a slightly remixed version of Jay-Z’s “Brooklyn’s Finest,” as Talib Kweli nods along and Mos Def air-drums outside the passenger door; there’s another where Kanye and Mos Def rap their verses from “Two Words” a cappella; there’s another when Kanye plays an unfinished version of “Family Business” for Scarface before it was released, before Kanye was signed, before it became the “Family Business” that I memorized, the song that I’m listening to right now. By the time I saw conversation footage between Kanye and his mother, Donda, I was, for a moment, as big a Kanye fan as I had been in 2004.

And yet, I know better. Intellectually, I understand misplaced admiration and the risks of putting my faith in public figures. I know that Kanye hasn’t betrayed me and doesn’t owe me the hopes of my youth. But if I’m honest with myself, the feelings I have for Kanye West aren’t sympathy or indifference. I hate Kanye.

I hate Kanye as if he assaulted me personally, whether it’s rational or not. Because no matter how much I understand advice like “Don’t make heroes of celebrities,” and even though I’ve given that exact advice myself, it’s always struck me as disingenuous.

When I think about belief in celebrities, I reflect on a word that has annoyed me for years: agnostic.

I recall Al Pacino in the 2003 movie The Recruit, when he tells a story about a priest who lost his faith. Back when I was dealing with my own struggles with faith, agnosticism offered itself as an easy comfort. To the question of whether I “believe in God,” I wanted to say, “I don’t know.” I wanted it to be enough—not for others, but for myself. I desperately wanted it to be that easy, but it never sat well with me. Because to call oneself agnostic in response to “Do I believe in God?” is to not answer the question. The question is about belief—that is, whether one accepts something to be true, whether one has faith in that thing. In other words, what do I think, not what do I know.

I can’t tell you the number of times I googled the definition of agnostic—“a person who believes that nothing is known or can be known of the existence or nature of God … a person who claims neither faith nor disbelief in God”—trying to make sense of how we’ve come to accept it as a fair answer to the question of one’s belief in God. To respond with agnosticism is just to say what’s also true of both believers and atheists: They don’t know in an empirical way. It’s an intellectual cop-out that misses the point of the question of belief, and the uncomfortable truth behind it: I can’t always choose what I believe. That belief might change, and I can influence it by what I expose myself to, but at its base level, belief exists in spite of what I want. I believe, or I don’t.

The truth is, we all believe in public figures, and anyone who says they’ve never loved a celebrity enough to be hurt by them is lying.

So far, jeen-yuhs is both a monument to the Kanye West I loved, and a rose on the burial plot of a hero I left behind. And there will be more documentaries of heroes I loved and lost: One moment it’s jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, and the next it’s We Need to Talk About Cosby, or worse, some unexpected addition to my graveyard of heroes. Their phantoms peek from their tombs like Lazarus to tell me that they’re still alive, and to remind me of what they once meant to me, and I push them back inside and seal the entrance to buy myself time to decide what to do with them.

I’ve loved and lost enough childhood heroes that I should have learned my lesson by now—I just don’t know what that lesson is. All I know is that the lesson isn’t to stop believing in people, because I don’t have much control over belief. Maybe I should just be grateful for what their work meant to me at the time, and leave the cemetery.

***

My favorite reader email this week came from Susan, who responded to last week’s book giveaway, How to Not Die Alone, with this: “Dying alone doesn’t scare me. The only thing that does scare me about dying alone is related to my rescue dog … what would happen to her?”

Susan, I have this exact fear about my sudden death! My dog, Lily, would eventually have to pee in the apartment and she’d feel pretty bad about it. Plus I’d be dead.

To avoid our untimely deaths and save our pets, this week’s book giveaway is How to Drag a Body and Other Safety Tips You Hope You Never Need, by Judith Matloff. Matloff has taught countless safety seminars for journalists, especially women, so if you’ve ever wondered how you might survive a stampede or escape a country during a coup, this one’s for you. Just send me an email telling me if you’ve ever hated an artist you once loved. I’ll send the book to the first person who hits my inbox. You can reach me at humansbeing@theatlantic.com, or find me on Twitter at @JordanMCalhoun.