How Anti-Semitism Shaped the Ivy League as We Know It

America’s most prestigious universities became elite through policies designed to keep Jews out of them.

A quick note: For The Atlantic’s website this week, I wrote a piece entitled “How Not to Talk About the Holocaust.” If you’re exhausted by the ways that our public discourse routinely appropriates the murders of millions for its petty political debates and are looking for a better way to approach the subject, this one is for you. Now back to our regular programming.

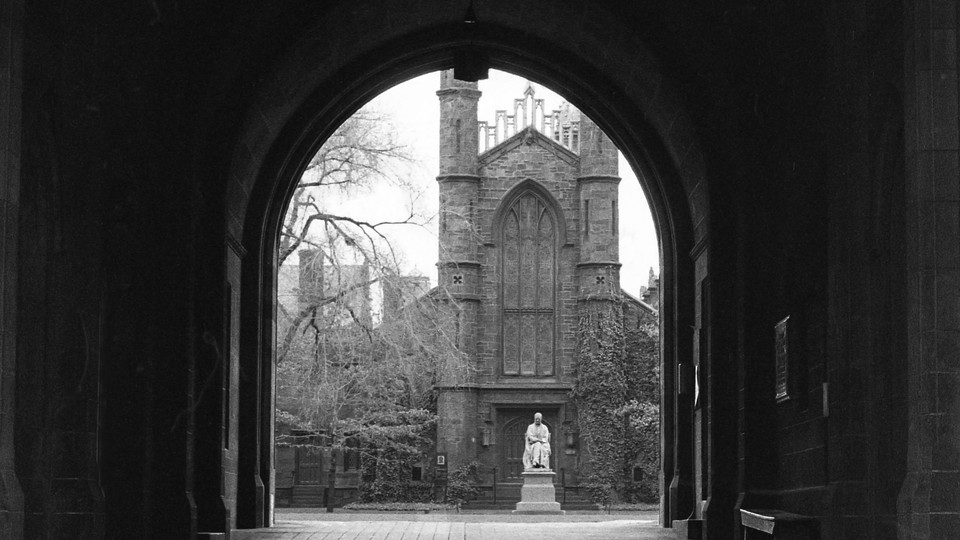

Mark Oppenheimer is the consummate Ivy League insider. A Yale graduate who directed its journalism initiative for 16 years, he has advised freshmen, mentored reporters, and taught classes at the pinnacle of the American intellectual establishment. But recently, he has turned his discerning gaze on the very institutions that shaped him. The result is Gatecrashers, an engrossing podcast from Tablet Studios that offers a revealing and often disquieting look into how anti-Semitism molded the Ivy League as we know it.

A former New York Times religion columnist, Oppenheimer is a superb storyteller—part historian, part host, part gossip. He seamlessly combines original interviews with alumni and administrators with past research from scholars like Berkeley’s Jerome Karabel and the University of South Carolina’s Marcia G. Synnott. Through eight episodes, one for each Ivy school, the podcast takes listeners through time, beginning at Columbia in the 1920s and ending at Harvard in the present day. The result is both entertaining and unnerving, as it quickly becomes clear just how many things that we associate with these institutions—their selectivity, their extensive application processes, even their push for geographical diversity—stemmed from one overriding motivation: to keep Jews out.

The podcast itself is full of arresting moments, from a surprising rendition of a very anti-Semitic a cappella song from 1920s Columbia to a scion of the Rockefeller dynasty acknowledging that he shared some of the anti-Jewish stereotypes of his Princeton peers. The production also grapples with the uncomfortable echoes of the Ivy League’s treatment of Jews in the controversy over its treatment of Asian applicants.

Following the release of the first episodes of Gatecrashers, I talked with Mark about some of its remarkable revelations, including the ways that university administrators justified discriminating against Jews and how Columbia established a separate college to which it shunted its many unwanted Jewish applicants.

Yair Rosenberg: Okay, so I have to ask you about the song. The first episode of the podcast features a college a cappella group singing about how Columbia University is controlled by the Jews. The lyrics of this bizarre song are very real, but as you note, the tune for them was lost—and so you hired performers to bring it back to life. I have so many questions about this, but let’s start with just two: Why? And how?

Mark Oppenheimer: The song—with its line about how “the sheenys,” an old slur for Jews, “will go to hell”—was reported on in at least a couple of national magazines in the 1920s. I was so struck by the absurdity of there being a relatively well-known, anti-Semitic, a cappella fraternity ditty at Columbia that it seemed that the only way to convey how extraordinary this was was to actually allow people to hear it. That’s the why.

The how was that we reached out to our friend Noam Osband, who himself comes from an Orthodox Jewish background and who is also an exceptionally talented musician. I offered him the challenge of imagining what this song would have sounded like, and after several iterations, we found the kind of 1920s jazz-era a cappella feel that probably would have been the right flavor for the time.

Rosenberg: It sounds surprisingly authentic!

Oppenheimer: [laughs] I don’t think there’s any danger of it catching on, though.

Rosenberg: You use this song to set up the entire show, which tries to tease out all the different ways that the Ivy League worked to limit their Jewish enrollment. And a big takeaway from the podcast is that the very things that define the Ivy League today, from selectivity to legacy admissions, were often actually instituted as efforts to keep out Jews. Can you unpack how this all happened?

Oppenheimer: The first thing to understand is that everything we know about selective college admissions today is less than a century old. So if you go back to 1910 or 1920, the Ivy League schools were not particularly expensive. They were not particularly desirable, in that they didn't have five or 10 or 20 times as many applicants as there were spots. And they weren’t particularly rigorous about vetting students. They appealed to a fairly small, self-selecting group of mostly Protestant, mostly well-to-do, mostly male Americans. So how did we get from there to here today, when these schools are desirable, expensive, and have a very rigorous vetting process?

The answer is that most of those measures came about as part of the effort to limit the percentage of Jews in the student body. The extensive college application of multiple pages came about because they added questions to figure out if an applicant was Jewish, including What’s your religion? What is your father’s occupation? What is your mother’s maiden name? Where were your parents born? At some schools, they asked you to attach a photograph. Some began to require an interview. And that was in part so they could try to suss out if you were Jewish or not.

My favorite example is the push for geographical diversity. Today we see this movement as a somewhat virtuous thing: Who doesn’t want to go to a school that has students from all 50 states? But it originally came about because colleges were trying to limit the number of New Yorkers, who were disproportionately Jewish. And so schools like Columbia began to send admissions officers to recruit students in the West and the South, because they were more likely to get gentiles from those regions. So even something as benign as geographical diversity has its origins in this quite calculated scheme to push the number of Jewish students down.

The broader historical background here is that around 1900, all of these schools had very few Jews, but by the time of World War I, all of them had rising numbers of Jewish students. That’s because they were largely open-admission schools, and ambitious Jewish sons of immigrants from New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia were applying. They figured out that if they had a few bucks, they didn’t have to go to City College or Temple. They could go to Columbia or Princeton, which were not particularly expensive and not particularly hard to get into. And so the number of Jews began to soar and multiply during those years of heavy immigration.

Rosenberg: Why exactly did Jewish students want to go to these schools, though? Obviously, they were very interested, given that Jews were a tiny, single-digit percentage of the U.S. population, yet quickly came to comprise some 10 to 30 percent of these elite colleges, despite quotas and efforts to keep them out. But at the time, as you note, the Ivy League wasn’t even that selective or particularly intellectual. It was just a finishing school for the American elite. So what did Jews see in it? It sort of seems like they walked into these schools with nerdy educational and meritocratic notions that many of the actual students there rejected. But then over time, it feels as though the Ivy League refashioned itself into the sort of place that the Jews thought they were applying to.

Oppenheimer: Yeah, the irony is that in 1920, the average student at City College or NYU was substantially more interested in homework and in learning a lot than the average student at Yale, who had pretty good prospects of going into his father’s business.

In some ways, this was a matter of happenstance. In 1920, something like half of New York City public-school students were Jewish, both because there’d been heavy Jewish immigration, but also because Jews didn’t drop out in eighth grade. Their parents wanted them to stay in school. And so as the grades went on, they began to overtake other ethnicities as a percentage of students. This meant that of the students graduating high school in New York City in 1920, a very heavy number were Jewish. So it just stood to reason that the percentages of Jews at all of the four-year colleges, which were the gateways to the professions like law and medicine, were going to go up. City College had pretty much maxed out. It was overwhelmingly Jewish. Columbia’s numbers were similarly going to go up, which they did—not as high, but perhaps to a quarter or a third. But it was not because the Jews necessarily did careful research and figured out that these were highly intellectual places. Rather, they might have had some sense that they were higher-prestige places, which might offer you a better chance of getting into one of the professional schools.

Rosenberg: All of this seems to stem from a Jewish cultural commitment to education, which apparently distinguished the community from other groups. It reminds me of a semi-serious theory I’ve entertained, which is that college in the United States basically became a secularized yeshiva for an assimilating Jewish population—a place to get an education, but not a specifically Jewish one. After all, what are humanities doctoral programs if not a form of secular kollel, in which young adults spend years in a cloistered scholarly setting studying revered texts of questionable practical application, often funded by wealthy Jewish philanthropists?

But more seriously put: Did the Jews basically treat the college system like the yeshiva system, and over time re-create it in their image?

Oppenheimer: The real question you want to ask is: Why did so many Jews who aspired to nothing more than a stable, safe, non-intellectual middle-class living go to college? The reasons have to do with the disproportionate clustering of Jews in urban areas, and with some commitment to education for its own sake. Jews also tended to emigrate as families, so there was a little more of a fiscal cushion in the home. That meant that the boys and girls didn’t have to go to work right away, or as soon as possible. So you were a little more likely to let your son or daughter stay in school, graduate, and then go on to college. And of course, it also had to do with the fact that especially in New York, there was an extended kinship network and support system, and that provided information. So if one kid from the Lower East Side made it to Columbia, the whole Lower East Side knew about Columbia. And the Lower East Side was the greatest concentration of Jews in the world in 1920.

The yeshiva concept is not a terrible theory, but it actually runs up against the fact that Jews first made their mark in the upper echelons of doctoral work in the sciences, in a system that used federal grants and a kind of nascent system of federal science and medical funding to fund lots and lots of lab work. You had kids coming out of a school like Bronx Science, which may have been 80 or 90 percent Jewish at the time, going to college, and then sticking around to become scientists. And I’m not sure how closely that sort of advanced scientific-lab bench work relates to the yeshiva idea.

Rosenberg: Speaking of the sciences, you have this amazing story about Isaac Asimov, the famed science-fiction author, who applied to Columbia and was essentially rejected and shunted to an alternative campus, which the school had established for various undesirables, mostly Jews. Were there any other interesting people you came across who had that experience beyond Asimov that people would be surprised to know?

Oppenheimer: Seth Low Junior College is this extraordinary story. I didn’t discover it. It’s been written about primarily by undergraduate journalists at Columbia and Barnard several times over the past 25 years, but it has left almost no trace in the rest of the culture. If you look for it in the New York Times, it was never mentioned after it shut down in 1938. Before that, it would be mentioned when it played against City College or even Princeton at chess, but it largely disappeared.

I presume that most of its alumni either listed other schools where they got professional degrees as their alma maters, or perhaps listed Columbia College, which would have been slightly disingenuous, because Columbia College refused to grant these Seth Low Junior College students proper Columbia degrees. And so it’s very hard to figure out who went to Seth Low except by going into the archives. But based on my limited research, its most famous alumni were Isaac Asimov and the great Celtics coach and general manager Red Auerbach, who also went to Seth Low, where he played basketball because they did have a basketball team. I think he transferred to GW, where he completed his college career. But again, these were two Jewish boys who surely could have done the work at Columbia, but were told to stay down in Brooklyn at this special campus.

Rosenberg: In the podcast, you interview many older Ivy alumni, and you observe that a lot of them just accepted anti-Semitism as the cost of doing business. They plowed right through it and took as much as they could get out of the college experience, and often had a good time. The anti-Semitism, though quite real, was not as bad as where they came from, and in a way could even be seen as an improvement!

Oppenheimer: Or it was not as bad as they expected it to be.

Rosenberg: Yes! Though it seems from the podcast like the expectations of the Jews entering the Ivy League changed over time. Later students started to have higher expectations for their treatment. They slowly wanted to have kosher food—not hidden away in some house off campus, but on campus. Basically, they began to be more assertive. It sort of feels like there are two different populations of Jews with two different sets of expectations, and one comes to overtake the other over time.

Oppenheimer: Oh, absolutely. I think that after World War II, a growing percentage of Jews began to feel a sense of entitlement. And you have a real inflection point in the late 1950s, which is when sociologists like Will Herberg are talking about America as a country of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, with Jews as a co-equal partner—what another scholar has called “tri-faith America.” Jews felt that they should be represented in Congress. They felt that there should be a Cabinet member who’s Jewish. They certainly felt that overt anti-Semitism was not acceptable. And of course, America was on some unspoken level cognizant of the destruction of European Jewry, and everybody wanted to think of America as better than that. So there was more grounding to make claims for equality and equal treatment as the years wore on. And the more that other ethnic groups began to stake a claim for their own entitlement, the more that Jews felt that they could do the same.

Rosenberg: It becomes American to do so.

Oppenheimer: It becomes acceptable, indeed expected, in America, to have some pride in your ethnicity and to expect representation in all sectors of society. Also, as the Jewish numbers go up at a place like Columbia, and more slowly at Yale and Harvard, I think students are less afraid. There’s more solidarity. There’s a higher comfort level that allows people to say what they really feel.

Another thing is that the American campus changes after World War II. At Yale, for example, the people coming in who were veterans and on the GI Bill were much more likely to be middle class or working class, and much more likely to have come from public schools. So once you have the massive expansion of the university franchise to far more sectors of America after World War II, the whole game of Ivy League schools as these bastions of twee traditions like a cappella singing, making freshmen wear beanies, and bladderball at Yale, becomes something of an anachronism. They continue but they cease to constitute the mainstream culture of the schools in the 1940s and ’50s.

Yale instituted its coat-and-tie dress code in the dining halls in the 1950s, because they felt they had to civilize the barbarians. These weren’t Jews; it was mostly gentiles from the provinces and the sticks and the exurbs. They felt they had to civilize these guys or they would tear down the traditions.

Rosenberg: One justification you excavate that the Ivy League employed in order to defend its anti-Jewish admissions policies was the claim that too many Jews on campus would actually provoke resentment and create more anti-Semitism. According to this argument, the proper anti-anti-Semitic approach was to keep the number of Jews down to a reasonably small number, so that they would be unthreatening and no one would get too upset. That serious people convinced themselves of this is a great example of how everyone is righteous in their own mind. What are some of the other creative justifications you came across that universities used to justify their discrimination against Jews?

Oppenheimer: The first big one was that discriminating against Jews was good for the Jews. Another one was that the good kind of Jews actually wanted to keep out the bad kind of Jews. At Dartmouth, there were conversations with Jewish alumni from the 1890s and 1910s about how to manage the potential influx of less cultured, more recently immigrated Jewish students. Number three was the claim that children of immigrants weren’t particularly interested in the distinctive traditions of the Ivy League schools. So if you wanted to preserve singing and theatrical reviews and pageants, fencing and fraternity life, you had to keep up the number of gentiles, because they were the ones who cared about that stuff, while the Jews were just concerned with getting an education—getting in, taking classes, going home, doing homework, getting out.

Rosenberg: I believe you discuss this in the final episode of the podcast, but some of the same justifications used to keep Jews out have come up in the very heated debates over the Ivy League’s treatment of Asian students.

Oppenheimer: Yeah, we are certainly going to get into the question of how the history of the Jews is being used by litigants in the Harvard case that will be argued before the Supreme Court in October. I think there are both analogies and disanalogies, but you can’t ignore it, because the plaintiffs themselves have said, They did to us what they did to the Jews. That is: marking applicants down based on soft, subjective personality categories, because otherwise their scores would be so high and there would be too many East Asians for the administration to stomach.

I think a lot of anger surrounding the affirmative-action argument has to do with a lack of transparency. And one salutary effect that this court case has had is that it has forced all sides of the argument to look carefully at how admissions works. And admissions offices don’t like that. They don’t like it because they aren’t themselves comfortable with people knowing how they treat different minority groups, but also because they aren’t comfortable with people knowing how they treat athletes, or legacies, or people from different geographical regions. I will say that the absolute worst transcript I ever saw in my career as a freshman adviser at Yale belonged to a white, male rower from a prep school. There’s a lot that people would be angry about if there were perfect knowledge about admissions.

Rosenberg: Listening to the arc of history on this subject, it feels like there are two ways to look at the Ivy League’s treatment of Jews over the decades. The first is a negative story. Jews are initially kept out through quotas, and then when those are no longer tenable and universities realize that they should value diversity of minorities to an extent, Jews get left out of affirmative action, and they don’t count for that either. So they lose in each era. None of the remedies address their situation. But there’s also a positive way to tell this story, which is that despite constant efforts to keep them out, Jews always found a way in, and because nothing was ever easy or handed to them, they constantly had to be twice as good to succeed, which ended up benefiting both the American Jewish community and the world.

You’ve spent decades immersed in this story as a participant and an observer. After all that you’ve seen, where do you land? Was the Ivy League good for the Jews?

Oppenheimer: I think the existence of the Ivy League schools has largely been a positive for the Jewish community. I think it offered several generations of post-immigration Jewish families a tangible way to feel that they had arrived, and gave a lot of them the cultural knowledge and the connections to be of more use to America.

I want people to understand that for most Jewish students at Ivy League schools over the last century, college was a lot of fun. Part of that was that the anti-Semitism was never so pervasive or visible that it ruined their day. But part of it also was that they felt good that in 10 years, in some cases, their family had made it from the pogroms to the Ivy League. The reality is that to have a college education in America in the 20th century, no matter who you were, was an extraordinary privilege in world historical terms, and it’s inspiring to see how avidly some Jewish students grasped at that privilege, even when there were people who didn’t want them there.

You can listen to Gatecrashers here, and find it wherever you get your podcasts.

Thank you for reading this edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the unexplored intersections of politics, culture, and religion. Don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already for more stories like this. And finally, I want to wish a happy Jewish New Year to all my readers, but especially those who read this far! If you’re looking for some Rosh Hashana reading, I recommend this piece.