Echoes From Odessa, the Onetime Jewish Metropolis Now Menaced by Putin

The Ukrainian city was a Jewish epicenter before being decimated by Hitler, Stalin and now Putin

This is a subscriber edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the unexplored intersections of politics, culture, and religion. Sign up for the newsletter here, and subscribe to The Atlantic for access to exclusives like this.

Before we dive into this week’s edition, I wanted to share with you an announcement that’s been in the works for a while. On Monday, March 14, at 1 p.m. eastern, I’ll be hosting a live show on Callin for Deep Shtetl readers. For those unfamiliar with this new medium, Callin is basically a live podcasting platform into which listeners can call in and speak to the host, like a radio show. I’ve been looking for ways to build our community and make it more interactive—to talk with you, not just at you—and this seemed like a great way to do it.

For the debut episode of Deep Shtetl Dialogues, I’m particularly excited that we’ll be joined by my friend Murtaza Hussain of The Intercept. As you’ll hear, the two of us have been having wide-ranging conversations about everything from religion to foreign policy over New York’s best kosher/halal deli for years, and now we’d like to bring you in on the action—which means that this will be the first time the words Rosenberg and Hussain will now take your questions will be spoken. Join us and witness history.

You can tune in on Monday at this link. (I even created a placeholder logo for the show that accidentally turned out vaguely anti-Semitic–looking, but you have to click through to see it.) While anyone can listen live on the web, in order to call in and chat with us, you’ll need to download the Callin app on your phone and tune in there. Once you’ve installed the app, I recommend following the new show, Deep Shtetl Dialogues, here, so you’ll get notified when it goes live.

Talk soon!

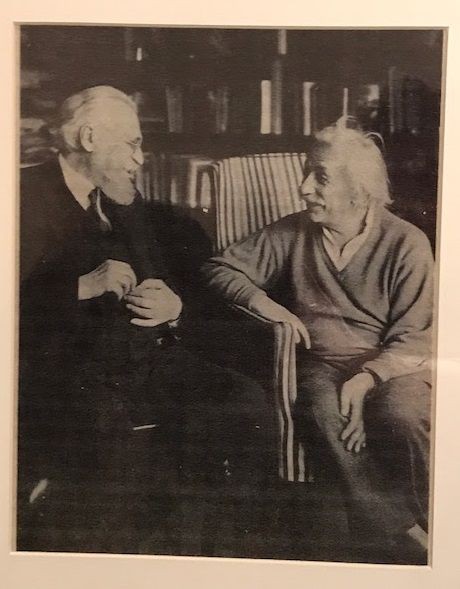

Last week, we heard from a convoy of Jews fleeing the Ukrainian city of Odessa in the face of Vladimir Putin’s “denazification” campaign. Today, Odessa is bracing for Russian assault. As I noted, this is a city redolent with Jewish history, whose population was once half Jewish—until it was decimated by Hitler and Stalin. But this background probably wasn’t news to longtime Deep Shtetl readers, because they’d already met the remarkable pre-Holocaust rabbi of Odessa, Chaim Tchernowitz. (In case you missed that edition, Tchernowitz was the religious muse who guided Albert Einstein in his explorations of the Jewish tradition.)

Home to the third-largest Jewish population at the time, Odessa was as unique as its rabbi. A port city whose ships brought not just trade but intellectual ferment, Odessa was host to every sort of Jew—devout, irreligious, Zionist, socialist, Yiddishist, and many more. And Chaim Tchernowitz, the city’s highly unusual Orthodox rabbi, was friends with all of them.

Through his recollections, one can catch a glimpse of the lost world of Odessa’s extraordinarily diverse Jewish life. Here are two such stories.

Making Modern Rabbis

Tchernowitz arrived in Odessa in 1897. He quickly set about transforming the local yeshiva, or Jewish school, into a full-fledged rabbinical seminary, where he sought to train the next generation of Orthodox rabbis and educators. But unlike most such schools, this one integrated traditional text study with modern critical methods. It boasted such teachers as Hayim Nahman Bialik, who would later become the national poet of Israel, and such students as the future biblical scholar Yehezkel Kaufmann. With its use of contemporary scholarly tools to mine classical Jewish works, the yeshiva was the only of its kind in all of Russia. Indeed, even the minutes of its staff meetings offer evidence of the school’s exceptional nature.

The protocols of these gatherings were recorded by Bialik, which is kind of like if Robert Frost took the minutes at a PTA meeting. The records reveal that Tchernowitz carefully evaluated each prospective student based on their ability to grapple with both traditional and nontraditional texts. The scholar Benjamin Hoffseyer pithily summarizes one of Bialik’s amusing notes in his 1967 Hebrew dissertation on the Odessa yeshiva (my translation):

On November 10, 1902, Rabbi Tchernowitz gave news of the acceptance of four new students … We read in the protocol that two of the four have skills that are “suited to the program.” One, however, “while adept in the study of the Talmud, knows nothing of secular disciplines.” And the other “knows nothing of either.”

Needless to say, only a select few Orthodox seminaries in history have appraised their students based on such dual criteria. This unusual commitment to secular studies was a clear reflection of the commitments of the school’s unusual dean. Surveying the distinguished, ideologically diverse faculty that Tchernowitz assembled for his yeshiva, and the attention he paid to the school’s nontraditional components, it is easy to understand the assertion of Lionel Trilling, the great American literary critic, that:

No one who ever encountered in America the striking figure of Dr. Chaim Tchernowitz, the great scholar of the Talmud and formerly the Chief Rabbi of Odessa, a man of Jovian port and large, free mind, would be inclined to conclude that there was but a single season of the heart available to a Jew of Odessa.

But my favorite Tchernowitz story from Odessa is about the time he sat down with a famous Jewish skeptic and they started editing the Talmud.

The Talmud, New and Improved

One of the towering figures Tchernowitz befriended upon his arrival in Odessa was Shalom Yaakov Abramovich, better known by his pen name, Mendele Mocher Sforim (“Mendele the Bookseller”). Today, Mendele is celebrated as a founding father of modern Yiddish and Hebrew literature. In Odessa, he was a dean of the maskilim—the enlightened skeptics of traditional Judaism. Raised religious and trained to be a rabbi, he became disillusioned with Orthodoxy, and his literary output reflected this sensibility. But just because he was something of a heretic didn’t mean he abandoned the texts of the tradition, which he continued to study, including with the city’s rabbi.

As Tchernowitz tells it, this is how the two men came to revise the Babylonian Talmud, the notoriously convoluted Aramaic compendium that underlies Jewish law. In an essay recounting his relationship with Mendele, the rabbi writes:

Mendele was not a scholar in the traditional sense, but he was exceptionally sharp and could quickly apprehend a Talmudic topic, even the most difficult and involved. He once began teaching me the opening section of tractate Bava Kama as a teacher would a student. He went line by line and would ask me, “If we were to delete this sentence, would the back-and-forth of the Talmud still be clear?” If I replied “yes,” he would immediately cross it out with a pencil.

It’s worth pausing to imagine this scene: A skeptical Jewish fiction writer pulls the Talmud off his shelf, then proceeds to slice and dice its contents in front of the local rabbi. The fact that Tchernowitz was fascinated by this, rather than outraged, tells you a lot about him. Indeed, the rabbi later took intellectual inspiration from this moment:

When we finished, I realized that two-thirds of the text had been eliminated without major loss to the contents. In this way, Mendele and I deleted a number of chapters and sections from the tractate, and I was surprised to discover that it was possible to abbreviate it dramatically. At that moment, I hit upon the idea of publishing an abridged version of the Talmud—a project which I would embark on years later.

This quotation is my translation from Tchernowitz’s original Hebrew account, but you can read a 1948 English adaptation of the essay in Commentary here. Tchernowitz never did finish what he called his Kitzur ha-Talmud, or abridged Talmud, but he did succeed in publishing abbreviated versions of several tractates.

The Odessa of 2022 is not the Odessa of 1922. But over the last few decades, its Jewish community has worked valiantly to rebuild itself piece by piece. Indeed, the city’s Jews have survived even worse than today’s devastation. The next chapters of its illustrious Jewish legacy remain to be written, long after Putin and his ilk have passed from the scene.

This is a subscriber-only edition of Deep Shtetl, so if you were forwarded this email, found the conversation valuable, and want to join it, please subscribe to The Atlantic. We’d love to have you.