What Putin’s ‘Denazification’ of Ukraine Really Looks Like

Fleeing Russia’s onslaught, a rabbi leads children from Odessa’s Jewish community through the Carpathian Mountains.

This is a free edition of Yair Rosenberg’s newsletter, Deep Shtetl. Sign up here.

“I once thought that I was a freak,” says Rabbi Refael Kruskal, the vice president of the Jewish community in Odessa, a port city in Ukraine. While many others in the country doubted the prospect of a Russian invasion, Kruskal—the son of a Holocaust survivor—took his cues not from the headlines but from Jewish history. “I had supplies on trucks. I had generators prepared. I said there’s gonna be a rush on gas stations, so I had gas prepared for the buses on the way.”

He ended up needing every gallon.

Hoping to check in on his journey, I sent Kruskal a message last night, assuming he was asleep and would see it in the morning. Instead, he wrote back immediately. It was 4 a.m., and he was still at work. We spoke by phone this morning.

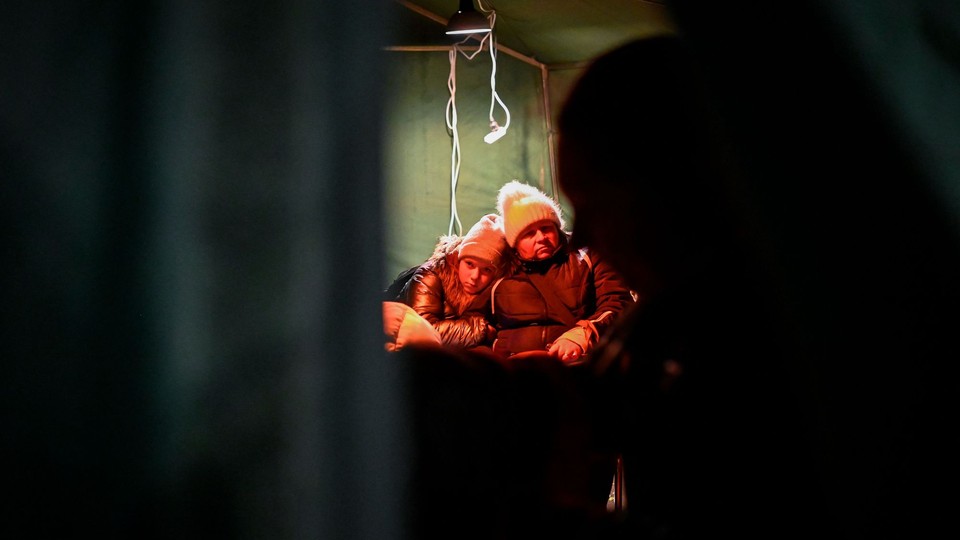

Kruskal oversees Tikva Odessa, a network of Jewish schools, orphanages, and community-care programs that encompasses some 1,000 people. When Russian bombs began to fall last Thursday night, and one exploded near Tikva’s girls’ home, Kruskal and his team decided it was time to leave. The call was made at 7 a.m. on Friday. By 10:30 a.m., he and his staff were on the road with hundreds of orphans, heading for prearranged shelter beyond the Carpathian Mountains. Others from their community headed for the border and crossed into Moldova.

“There were people in the Second World War who didn’t believe, and they and their communities were wiped out,” he said. “We prefer to be cautious and make sure that our communities are safe.”

Before the convoy set out, Kruskal posted a brief video from the evacuated central synagogue in Odessa, his voice catching as he asked those watching to pray for them.

Religious Jews like Kruskal and the children in his care normally do not travel or use electricity from sundown on Friday to Saturday night, in observance of the Jewish sabbath. But Jewish law permits the violation of the sabbath for pikuach nefesh—the preservation of human life. And so the community drove through shabbat, stopping at a gas station to make kiddush, the traditional blessing over the wine.

“You never expect to be standing in front of hundreds of people in your care in the middle of a cold gas station in Ukraine and making kiddush for them and they’re crying,” Kruskal said. “It was very overwhelming.”

On Twitter on Friday morning, anticipating the difficult sabbath ahead, Kruskal wrote in Hebrew: “Tonight, many Jews from Odessa will have to be on the road to evacuate to a more secure place. I ask our brethren in Israel who do not keep Shabbat to keep this Shabbat for us.”

It was a difficult journey. “Every 70 miles, we stopped to see which roads were being mined by the Ukrainians so the Russian tanks couldn’t progress, and which roads were being bombed by the Russians, where it was less safe to go,” Kruskal recalled.

It took the first bus 27 hours to arrive at its destination, a campground just beyond the mountains. The final bus arrived after 33 hours. Because the shelter hadn’t been sure if the Jewish children were coming, it had already given out 90 of the spots to other refugees. Kruskal procured mattresses for the kids, and he and another staffer slept in the infirmary area for the night.

He has been heartened to see the children adjusting to their surroundings. “I was happy when about two hours after I arrived—I was shattered, I’d been on the phone the whole time—two boys came to me and said, ‘Do you think you can ask the owner to open the football pitches?’ At least, as traumatized as they’ve been, they’re saying normal things.”

But he has also seen the fear lurking not far beneath the surface. After the first night in the medical wing, Kruskal needed to find a new place to sleep, and was quickly accosted by alarmed children asking why he was leaving. He assured them that he was not. “There’s certainly a lot of trauma here, a lot of uncertainty,” he said. “People don’t know what’s going on.”

Though he almost doesn’t show it, the evacuation has also been hard on Kruskal himself, who arrived in Odessa in 1999 at the Jewish community’s invitation. Odessa was once a cradle of Jewish civilization—home to the third-largest Jewish population in the world, and a hotbed of Jewish political activism and literary life. At its height, the city was half Jewish. But after the pogroms, the Holocaust, and Stalin’s purges, that percentage dropped to just 6 percent. Kruskal has spent 22 years building it back up. And then, suddenly, he was leaving it behind for an uncertain future.

Vladimir Putin has repeatedly claimed to be “denazifying” Ukraine, a disingenuous pretext echoed by an online army of apologists. But this exodus of innocents is the true face of his campaign. “I walked past one girl—her mother is in Kharkiv with her grandmother, and the city’s being shelled—and she’s crying on the side,” said Kruskal. “It’s just unbelievable what one man can do.”

Tikva is running an emergency campaign for donors on its website. But even those who need help themselves are trying to help others. Having evacuated the city, Tikva opened its buildings to those in need back in Odessa. This, too, is a lesson from Jewish experience. “We have to stay together and look after each other until this is over,” Kruskal said. “It’s very, very important because we know how other people helped us during the Second World War. We have to be the same and do the same to help others. We’re not only here to look after ourselves; we’re here to look out for anyone who needs help.”

Despite the chaos and devastation, Kruskal has no intention of giving up. In his emotional farewell video from the Odessa synagogue, he opened with the words recited by religious Jews when they finish a tractate of the Talmud: “hadran alach, ve-hadrach alan”—“we will return to you, and you will be returned to us.”

This is a free edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the intersection of politics, culture, and religion. You can sign up here to get future free editions in your inbox. But to get access to all editions, including exclusive subscriber posts, and to support this work, please subscribe to The Atlantic here.