Your Bubble Is Not the Culture

From "Hamilton" to "Harry Potter," critics keep misreading popular culture and writing off things that their audiences love. Why?

I don’t have anything against cultural and ideological bubbles. My family is a bubble. We have a host of in-jokes that no one else will get, and a bunch of tastes that many others do not share. We regularly eat a dish called “tuna quiche,” which brings us joy even as it causes others to break for the nearest exit. This dynamic holds true on a larger scale, from religious communities to pop-culture fandoms: Most bubbles are a wonderful way to unite people through shared experience. They only become toxic when their members start believing in toxic things and then attempt to impose them on others—sort of like if my family got really into cyanide quiche and started bringing it to synagogue and insisting everyone try it. In the real world, this looks like conspiratorial cultures, from QAnon to societal anti-Semitism to 2020-election truthers. Thankfully, most bubbles are not like this.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t have negative impacts. Some bubbles don’t literally poison the minds or bodies of adherents, but they do disconnect individuals from the broader community and make it harder for them to relate to the people around them, which has negative consequences for society at large.

Lately, something like this has been happening in our cultural discourse.

As a college student, I was the movies editor of The Harvard Crimson. I’d joke that this made me the most prestigious amateur film critic in America. In reality, of course, I was just a kid with no actual influence or expertise, writing in my dorm room. In another, gentler universe, I’d have followed that path professionally, but unfortunately, I felt some nagging social responsibility to write about weightier topics like national politics, conspiracy theories, and anti-Semitism. Nonetheless, I continue to be an avid consumer of cultural criticism, and occasionally don my old hat to engage in the conversation.

Recently, though, I’ve noticed something weird about that conversation. Here’s a recent sampling of cultural critics writing about some pretty popular properties today:

Vox: “Sunny, wholesome, nominated-for-16-Emmys Parks and Recreation is now widely considered an overrated and tunnel-visioned portrait of the failures of Obama-era liberalism. Iconic and beloved Harry Potter is the neoliberal fantasy of a transphobe. Perhaps most dramatic of all is the rapid fall of Hamilton and its creator and star, Lin-Manuel Miranda … The real sign that the shibboleths of millennial pop culture have lost their cultural capital is that right now, they mostly just feel kind of cringe.”

Insider: “There is no good way to introduce Harry Potter to the next generation.”

The Ringer on Miranda: “It’s hard to think of a popular entertainer who’s suffered a starker whiplash in critical regard over the past decade … He’s cringe, but that’s Broadway, baby.”

The A.V. Club: “Fantastic Beasts 3 has a new title, new release date, same old massively disappointing writer: J.K. Rowling’s script will reveal The Secrets Of Dumbledore next April, if anyone can bring themselves to care.”

Rolling Stone: “Thanks to the labors of TikTok teens, a wider audience now has to confront that we may have been ‘Wrong About’ Miranda and Hamilton.”

Polygon: “The Wizarding World canon already divides the fanbase … But Rowling and Warner Bros. continue to chug out Wizarding World content that doesn’t explore stories that fans are interested in.”

Now, here’s what’s actually been happening in the real world:

This week, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s soundtrack for the hit Disney film Encanto displaced Adele’s 30 as the No. 1 album on the Billboard 200. At the same time, Miranda himself hit No. 1 on the Hot 100 Songwriters Chart for the first time in his career. It’s only the latest in a string of successes for the Hamilton creator, which include this past year’s Tick, Tick … Boom!, his Netflix adaptation of Jonathan Larson’s musical; the HBO film version of Miranda’s Tony-winning musical In the Heights; and Freestyle Love Supreme, his improv hip-hop Broadway show. Back in 2020, after the film version of Hamilton was released on Disney+, the cast album for the musical surged to No. 2 on the Billboard chart, five years after its premiere. It was the highest-charting cast album since 1969. As of this writing, the album ranks as No. 47, and has never fallen out of the top 200 since it first appeared.

As NBC reporter Benjy Sarlin put it, “The people saying Lin-Manuel Miranda has had some fall from grace because leftist Twitter doesn’t like him probably don’t notice every kid now associates him with blockbuster Disney musicals, which is about the biggest cultural cachet possible.”

It’s harder to gauge the continued salience of Parks and Recreation, but we did get a clue a little over a year ago, when the cast reunited for a one-off coronavirus-relief special. That episode—the first since the show concluded in 2015—drew comparable ratings to the original series, beat everything else on prime-time television that night, and raised $2.8 million in relief funds.

As for the Wizarding World: In 2020, the year Rowling made her most pointed statements on transgender issues, Harry Potter sales went up for its British publisher, Bloomsbury. In fact, “the paperback edition of ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’ was the fifth-bestselling children’s book of 2020 to date, 23 years after it was first published.” This past June, the biggest Harry Potter store in the world opened in New York City to rave reviews. HBO is currently airing several specials celebrating 20 years since the first Harry Potter movie. And despite the pandemic, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child has reopened on Broadway. The persistent popularity of Potter probably explains why outlets whose critics insist that the Potter party is over keep publishing pieces about the franchise. Insider, for example, has run over 80 such items—from “What It’s Like to Visit the Real-Life Diagon Alley” to “28 Major ‘Harry Potter’ Movie Deaths, Ranked From Least to Most Heartbreaking”—in the last year alone. Some cultural critics may not know that Harry Potter is still massively popular, but the people running the click farms they work for do.

Rowling herself is doing just fine as well. The latest entry in her successful Cormoran Strike detective series, which she writes under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, was an international best seller and moved more copies upon release than any prior book in the series. In May, it won Best Crime and Thriller Fiction Book of the Year at the British Book Awards. (Insider, on the other hand, called this same book “poorly received.”) Rowling’s October children’s book, The Christmas Pig, another international best seller, sold over 60,000 copies in just its first week. (The entertainment site Giant Freakin Robot: “JK Rowling Facing Brutal Fan Reactions to New Children’s Book.”) Simply put, Rowling sells more books in a day than the critics claiming she’s been shunned will sell in a lifetime.

Obviously, none of these statistics tell you much about the moral merits of any position or argument put forward by Miranda, Parks and Recreation, or Rowling. But they do tell you about the culture and its preferences. Yet the average person wouldn’t know most of this from consuming much of what passes for trendy internet cultural criticism.

What explains this discrepancy between what some critics are claiming and what consumers are actually enjoying? Here are three reasons:

Being a critic can lead you to lose sight of the experience of the audience. When I was a movie reviewer in college, I took it upon myself to cover one of the more significant cinematic works of our age, How to Train Your Dragon. When I arrived at the advance screening in Boston, I discovered that the marketing team had done something clever: They brought in an entire class of little kids to watch the movie with us. The promoters understood that adult critics were not necessarily this film’s target audience, so they wanted to make sure that we got to experience it with some viewers who were. (It worked: I gave the movie four out of five stars.)

But this disjunction between reviewer and audience doesn’t just happen with children’s movies. The problem with being a professional critic is that you end up consuming so much culture that you stop processing it like a normal person. Once you’ve seen your 20th car chase of the year, the novelty begins to wear off. But the average audience member is not mainlining movies like that. A paint-by-numbers action or comedy flick may feel completely fresh to them—and so may a banal superhero movie or the latest Harry Potter or Star Wars release.

One of many things that made the late Roger Ebert great was that he retained the ability to watch something as a conventional moviegoer and rate it accordingly, even if as a critic, he’d seen 100 similar films and had a different reaction from that perspective. He knew that most people who go to the movies are not looking for the next great work of cinema, but rather something with which to enjoyably pass an afternoon with their families. So he would do fancy film events where he’d discuss the technicalities of cinematography in the work of Martin Scorsese, and then turn around and give four stars to Iron Man.

It’s actually pretty hard to make this pivot. Here’s an example from my own life. I can’t bring myself to watch Red Notice, the Netflix action comedy starring The Rock, Gal Gadot, and Ryan Reynolds. To put it gently, it’s not the sort of film designed to tickle the senses of cultural epicures. It also became the No. 1 movie in 93 countries, leading Netflix to commission two sequels. Yet I doubt you’ve read much about the film or its fans, because it’s geared toward audiences and not critics like me.

I know that my own preferences here are not the norm. But when critics lose sight of why most people consume culture, they start missing what makes most things popular. In their search for significance, they forget about the fun.

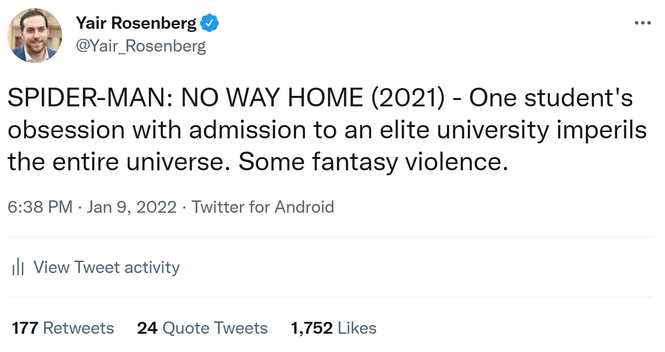

Many cultural critics live in an unrepresentative internet bubble. Much of the current divergence between elite discourse and popular preference can be reduced to a simple heuristic: Most critics are on Twitter; most consumers are not. If you examine the coverage proclaiming the end of Harry Potter or Lin-Manuel Miranda, or castigating any other wildly successful cultural product or personality, you’ll quickly spot a pattern: The only evidence they tend to cite is an assortment of tweets.

But just because something makes waves on Twitter doesn’t mean it actually matters to most people. According to the Pew Research Center, only 23 percent of U.S. adults use Twitter, and of those users, “the most active 25% … produced 97% of all tweets.” In other words, nearly all tweets come from less than 6 percent of American adults. This is not a remotely good representation of public opinion, let alone newsworthiness, and treating it as such will inevitably result in wrong conclusions.

To be clear, my own profession is just as guilty of this practice. Political reporters and elite opinion-makers are often similarly misled by viral content on social media and mistake Twitter trends for electoral realities. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, I’ve fallen for this ruse myself, most notably when I discounted the viability of Donald Trump’s 2016 candidacy because my peers on social media did. To take another example, Joe Biden had few Twitter fans during the 2020 Democratic primary, but he had many more voters. Twitter is real life for the people who are on it, but most people are not on Twitter.

Put another way, it’s true that Hamilton and Harry Potter and Parks and Recreation are “cringe.” But they’re only cringe in a narrow and unrepresentative corner of the culture that is disproportionately inhabited by critics, not in the rest of the culture those critics are meant to be covering.

Just as most people do not watch CNN and have no idea what’s in President Biden’s proposed Build Back Better Act, most people are not even aware of J. K. Rowling’s tweeted views on transgender topics, let alone have had those views color their engagement with her writing. They don’t know about random Twitter-stoked controversies involving Aaron Sorkin or niche TikTok roasts of Lin-Manuel Miranda. They just consume culture that they like and go on with their day. If someone can’t appreciate popular culture in this way, they will have trouble understanding why most of it is popular with its audience. This doesn’t mean we cannot or should not consider other issues—like the politics of certain creators or creative choices—when evaluating art. We should! But if a critic allows those to dominate and color every piece of commentary they write, they will gradually become alienated from the very culture they’re attempting to cover.

If this is true, though, why do some critics nonetheless reduce their evaluation of art to its perceived politics?

Culture writers, like most people, want to justify their existence and significance. As an undergrad, I took a popular course about classical music called “First Nights.” The class surveyed several great works of music through the centuries, and culminated in the performance of a new piece by a live string quartet. As part of that process, we got to interview the musicians. Someone asked them the obvious question: “What good does classical music provide to society?” I’ve never forgotten the answer one of the performers gave. “Well,” he said, “I look around at our planet and see humanity destroying itself through climate change, conflict, and squandering natural resources, and I figure that one day, when we’ve destroyed ourselves, some civilization or aliens will find this music and realize that there was more to us than that.”

What amazed me was that this talented performer couldn’t just say, “I love music, and I’m lucky enough to have found a way to get paid to play it and bring some joy to those who also enjoy it, while supporting myself and my family.” He had to be saving our entire civilization’s reputation in the eyes of extraterrestrials. Ever since then, I’ve been attuned to the heroic stories people tell about their jobs, as opposed to the reality of those jobs.

Everyone wants to believe they’re saving the world. Myself included. I noted earlier that I went into journalism rather than film criticism because I felt vaguely embarrassed about pursuing something less socially significant. I suspect some actual critics feel similarly conflicted about their work. Watching movies and television for a living can seem privileged and indulgent compared to other vocations, especially in a world on fire. But once you start treating TV and film as politics, suddenly the project feels far more consequential.

I became a reporter to seek similar relevance, but the truth is, this profession is not that different. Journalists want to believe that they’re Woodward and Bernstein, speaking truth to power. Most of the time, we’re not. What we write will rarely change the world. And there’s no shame in that! Informing or entertaining people, earning an honest living, and putting food on the table for yourself and your loved ones—these are all good and praiseworthy things. But they are not the noble narrative that most people tell themselves about their work.

The deep-seated need to justify one’s own relevance is how we end up with cultural criticism that evaluates art as politics, rather than as art which also has political elements. It’s how we get Playstation 5 reviews that scold people for owning one and being excited about it, because purportedly only privileged people do things like that. I suspect that if folks felt less guilty about what they were doing, we’d get less of this sort of writing.

To be sure, criticism is not a purely populist endeavor. The role of a reviewer is not merely to follow and explain the crowd, but to evaluate art regardless of public opinion and hold it to the highest standard. But lots of what passes for criticism these days isn’t that; it’s just following a different, much smaller crowd, typically on social media. And this undermines the entire project. Cultural criticism—like any form of guidance—can’t be heard when it’s entirely disconnected from the people it’s meant to reach.

After all, if anything is “cringe,” it’s culture writers telling their audiences that they should hate the things that bring them joy, especially at such a difficult time.

This is a free edition of Deep Shtetl, a newsletter about the intersection of politics, culture, and religion. Sign up here to get future free editions in your inbox. But if you’d like to get access to all editions, including exclusive subscriber posts, and to support this work, please subscribe to The Atlantic here.