Israel’s Version of the Latinx Question

Activists and journalists often refer to Arab citizens of Israel as simply “Palestinians,” but the reality is messier—and can teach us about our own questions of identity

There’s much ado about Latinx among a certain subset of political and media commentators today. The rest of you, though, are probably already confused. Let me quickly explain. As my colleague Christian Paz recently detailed, the term Latinx was originally popularized by academics and activists to serve as a gender-neutral replacement for Latino/a. In recent years, the label has ballooned in popularity, and is now deployed constantly by mainstream media outlets from NPR to the New York Times, and by Democratic politicians from Elizabeth Warren to Joe Biden.

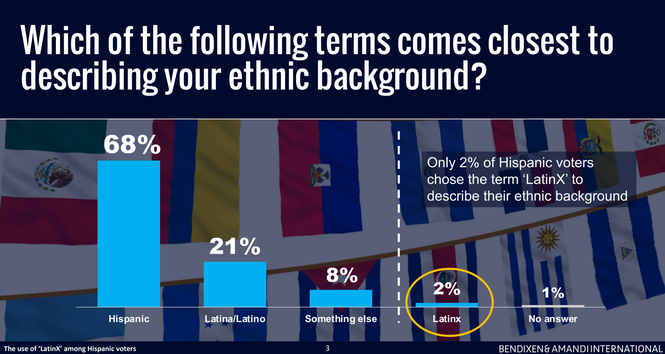

There’s just one tiny problem: A series of surveys have shown that most Latinos have never even heard of the word Latinx—and that many who have are actively opposed to it.

In August 2020, Pew found that only a quarter of Hispanics were familiar with Latinx, and just 3 percent of them used it. Fast forward to November 2021, and a new nationwide survey conducted by Latino pollster Fernand Amandi—who advised Barack Obama’s successful presidential campaigns—found that just 2 percent of respondents identified with Latinx. At the same time, 40 percent said that the term bothered or offended them, while 30 percent said they’d be less likely to back a politician or organization that employed it.

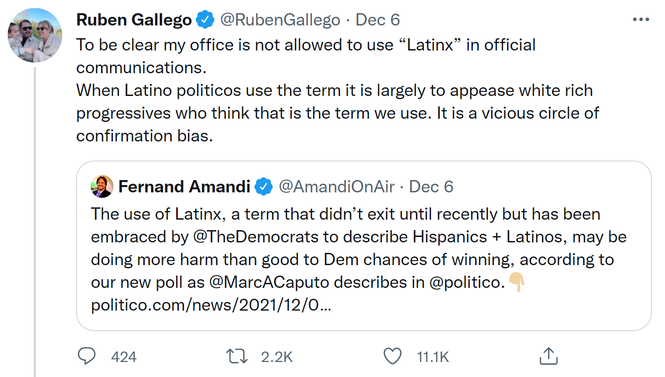

Another indicator of the term’s obscurity is the fact that many Latino politicians refuse to use it. As Paz reported, “Legislators and their staff shy away from it, and the word is almost never discussed among the country’s top Latino elected officials, despite outsize attention to it in mainstream media.”

Democrats have lost ground with Latino voters in recent elections, and some have pinned this on out-of-touch terminology like Latinx. But the obscure term is not the cause of the growing progressive problem with Latino voters. It’s a symptom. As Matt Yglesias writes:

The issue is that if you’ve got a group of people talking this way, it likely reflects a lack of direct engagement with the community in question, which is going to be a larger political problem …

And I think it speaks to a larger ideological issue, which is that progressives have been banking on the growing Hispanic population to create their hoped-for majority, but they seem very uninterested in paying attention to the actual views of Americans of Latin ancestry.

Put another way: The unearned prevalence of Latinx among progressive elites is a linguistic expression of a more fundamental disconnect between them and the community they’re trying to reach. It reflects a privileging of symbolism over substance and language over material concerns. This is politically perilous, because those who substitute ideological activist frames for on-the-ground engagement with a minority community will likely miss important things about it.

And this phenomenon doesn’t just happen in the United States.

Israel’s Latinx Problem

One fun thing about reporting on both domestic and international politics is that you quickly discover that the problems you thought were unique to your society actually aren’t. Indeed, examining those problems in another context can help you understand and address your own.

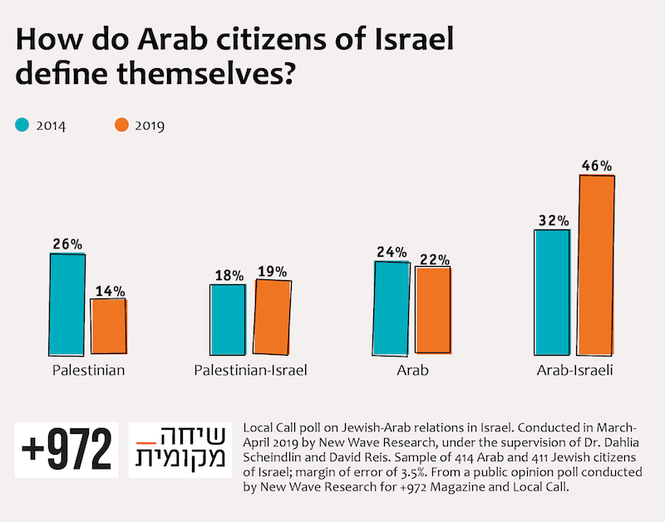

To that end, here’s a story that might sound familiar. In Israel, there is a minority community that is typically called one thing by activists and some in the media, but that calls itself many other things in surveys and polls. That community is the Arab community, which comprises 20 percent of Israel’s population. To some activists and journalists, they are simply “Palestinians,” separate and alienated from broader Israeli society. But that’s not what many tell pollsters.

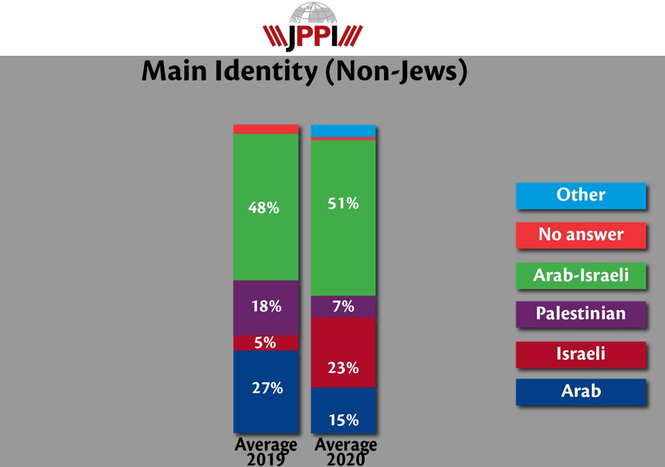

In 2019, a survey by progressive pollsters Dahlia Scheindlin and David Reis found that while 14 percent of Arabs in Israel identified as “Palestinian,” 19 percent preferred “Palestinian-Israeli,” 22 percent went with “Arab,” and a full 46 percent chose “Arab-Israeli.” In 2020, a survey by Professor Camil Fuchs, one of Israel’s top pollsters, offered a few more options—and got even more remarkable results. Given the option to identify as simply “Israeli,” 23 percent of Arab respondents picked that label. 15 percent chose “Arab,” while 51 percent opted for “Arab-Israeli.” Just 7 percent went with “Palestinian.”

This growing Arab identification with Israel is part of a broader pattern. Already in 2017, polls found that 60 percent of Arab citizens held a positive view of the Israeli state, even as 47 percent felt that they were “treated unequally.” Of the Arabs surveyed, 63 percent said that Israel was a “positive” place to live, compared with 34 percent who said it was not. Another survey that year found that 51 percent of Arabs in Israel described themselves as “quite proud” or “very proud” to be Israeli, while 56 percent of Arab respondents characterized the country’s situation as “good” or “very good”—compared with just 44 percent of Jewish respondents.

Yet if you search through the archives of most prestigious international news outlets and NGOs, you will find few stories that reflect any of these findings. I would not be surprised if this is the first you’ve heard about them. That’s because for some time, Arabs in Israel have been telling a different and more complicated story about themselves than the one being told about them by activist groups and major media outlets.

As in the United States, this disjunction between the narrative and the rank and file was exposed by its electoral consequences. In America, contrary to post-2016 elite expectations, Latino voters shifted toward Republicans. In Israel, Arab voters shifted toward Mansour Abbas’s Ra’am party, which ran on an explicit pledge to work with the next Israeli government, rather than protest outside it. It was a bold bet that required Abbas to split from the larger Joint List party and run on his own. The wager paid off: Abbas ended up winning nearly half the Arab party vote, helped cement the anti-Netanyahu coalition, and in November, enacted the largest funding allocation for Israel’s Arab community in the country’s history.

This was a tectonic shift in Arab participation in Israeli politics. It contradicted those on the right who had long cast the Arab community as an anti-Israeli fifth column, and those on the left who framed the population as alienated outsiders righteously opposed to the Israeli state. Yet as momentous as this shift was, it was entirely predictable if one dispassionately read the polls.

As it turned out, many Arabs in Israel didn’t want to disassociate from Israeli society; they just wanted their fair share of its promises to its citizens. They wanted to integrate, not separate. And they were willing to vote for parties and politicians who advanced that cause, even at the cost of deprioritizing—but not abandoning—Palestinian nationalism. This may have been anathema to certain left-wing activists and incomprehensible to anti-Arab right-wing racists, but it was—and is—an electoral reality. And it stems from the fact that the Arab community in Israel is far more diverse and complex than many give it credit for.

To make sense of all this, I spoke to Mohammad Darawshe, a Palestinian activist and scholar who serves as the strategic director for the Center for Shared Society at Givat Haviva. Darawshe previously ran campaigns for Arab political parties, and he thinks more about questions of identity than most, because as a Palestinian in Israel, he has to.

“Our identity as Arab citizens is not the same as the identity of other Israelis,” he explained. “It’s not the same as the identity of other Palestinians. It’s not the same as the identity of other Arabs. It’s an identity that is emerging to be something completely new, probably moving further and further into more Israelization, but still carrying the weight of Palestinian and Arab identity.”

Clearly, this experience doesn’t reduce to a simple label. “When Professor Tamar Hermann,” a leading researcher in this field, “gives Arab citizens three choices of self-definition, she gets 17 different variations” in response, Darawshe said. “But the amazing part is that 70 percent integrate the term Israel into their identity … and 70 percent as well choose the term Palestine … If you combine the two things together, you get to 140 percent. Which leads me to say: Who says that identity is a 100 percent zero-sum game? Identity is more like circles that overlap.”

Darawshe calls minority communities like his that are still finding their place in a majority society “communities in progress.” These groups are “not settled yet with their unique identity, because their identity is basically emerging as a new identity.” That identity is not static and it is not one thing. It evolves over time in response to events and the treatment of the broader society.

This is an insight that applies far beyond the borders of Israel and Palestine.

How to Avoid the Latinx Trap

Fundamentally, the problem with Latinx is not the word Latinx, which is a real term that small but real numbers of people apply to themselves. The problem is failing to engage with the entirety of the Hispanic American community on its own terms.

As Darawshe says, attempts to reduce and simplify a complex minority to a single label and experience will invariably result in wrong conclusions. Instead, whether it is Arabs in Israel, Latinos in America, Jews around the world, or any other minority group, we ought to grant these communities the same level of complexity that we would grant our own. Leaders and activists need to speak to different social and economic strata of these demographics, and not just the people who look and sound most like them or echo their own assumptions and opinions.

Only by appreciating the dazzling diversity of minority communities, and resisting the urge to reduce them to a monolith, will we be able to truly understand them. That’s useful advice not just for politicians, but for anyone hoping to build a better, more empathetic society.