Why Facebook and Twitter Won’t Ban Anti-Semitism

And neither will any other major social media platform

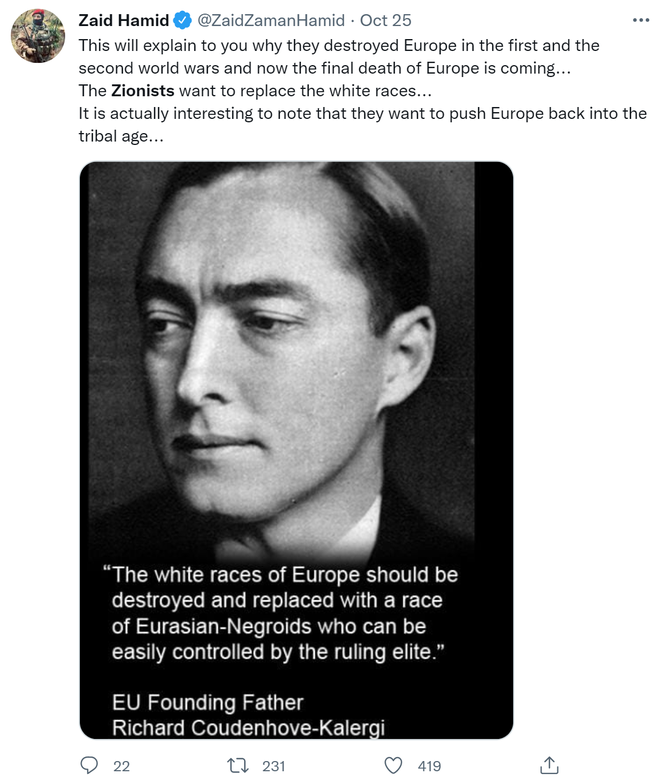

Here is a real tweet from this past Friday, posted by a verified account with over 300,000 followers. It is still up right now:

If you’re like me, this claim poses many questions. For one, if Jews were really trying to kill off the gentiles, why would they go through all the trouble of artificially engineering a global food shortage when they could just poison the food? Who is making these dubious decisions at global Zionist HQ, and how did they the get the job? And how does falsely accusing Jews—sorry, “Zionists”—of committing genocide not violate Twitter’s own rules against bigotry and incitement?

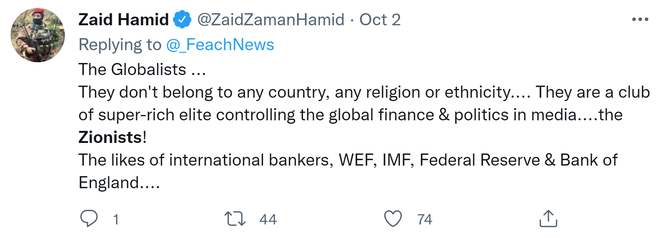

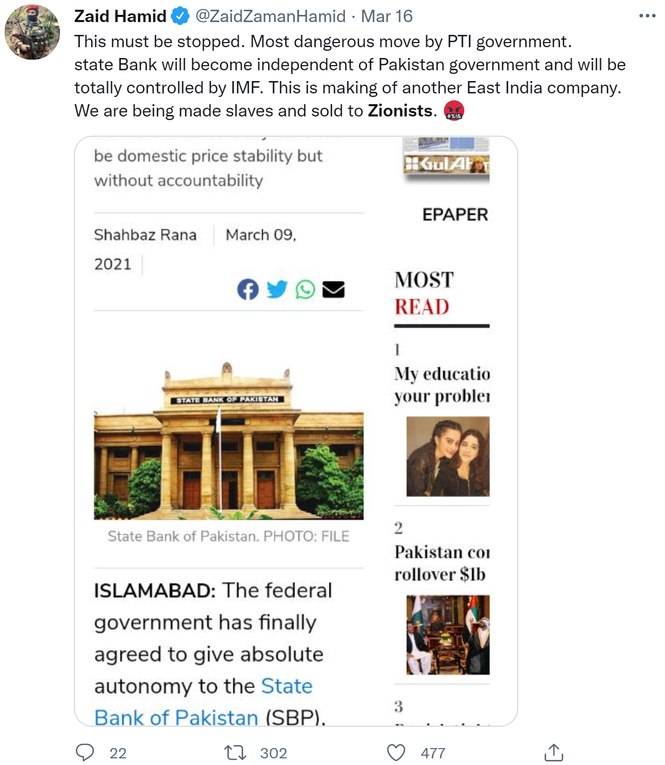

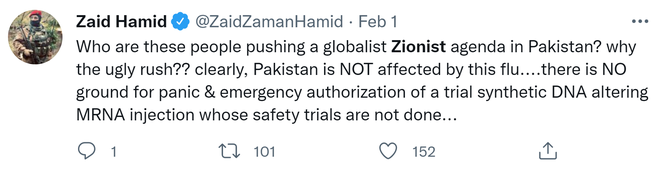

You will not find the answers to these questions if you look through this Pakistani commentator’s Twitter feed. But you will find that he has exactly one trick: Blaming Jews for everything bad he sees in the world, real or imagined, and then replacing the word “Jews” with “Zionists” in order to pretend that he is not anti-Semitic.

This person is not important. He is a sad and deluded man who is not very interesting in his own right. But his continued presence on Twitter and Facebook, where he has over 1 million followers, is quite revealing about social-media companies, the people who run them, and the reasons they don’t put a stop to anti-Jewish bigotry on their platforms.

They lack the cultural competency to identify anti-Semitism.

Anti-Semitism is not just people with swastika avatars going around calling people “kikes.” It is an ancient, byzantine conspiracy theory that blames Jews for all of the world’s many problems. Teaching your algorithms and underpaid content moderators to remove tweets with obvious slurs will not address most anti-Semitism. Without serious schooling in anti-Jewish prejudice and its many manifestations, these arbiters will not be able to identify anti-Jewish conspiracy theories—“the Jews control the government/economy/media,” “the Jews were behind the slave trade,” etc.—as anti-Semitic. They will not know that anti-Semites love to lazily swap “Jew” with “Zionist” or “Israeli” in their ramblings to maintain plausible deniability, and that this evasion spans from Trump rallygoers to the foreign minister of Pakistan. In other words, the moderators will not be able to identify all of the tweets cited above as anti-Semitic, even though they obviously are—which is why all of them are still up and their author continues spreading his cartoonishly anti-Semitic content to his legion of fans. If you don’t understand a bigotry, you can’t possibly fight it. And social-media companies do not understand anti-Semitism.

Social-media companies rarely police non-American content, and most anti-Semitism isn’t American.

Over 90 percent of Facebook’s monthly users now reside outside North America. But last month, the Wall Street Journal exposed just how little effort Facebook devotes to moderating their material:

This gap has clear consequences when it comes to combatting anti-Semitism. While there are significant pockets of anti-Semitism in the United States, it is one of the least anti-Semitic countries in the world. By contrast, prejudice against Jews is far more prevalent in Europe and the Middle East, two places that (not coincidentally) mostly cleansed themselves of Jews over the last century. But because social-media platforms like Facebook are focused on American content, the majority of anti-Semitic content is overlooked—like the overseas conspiracy theories that prompted this piece.

In essence, that’s a structural explanation for this problem. But I think there is also a social component to it, which brings us to our last point:

Rampant global anti-Semitism isn’t embarrassing.

If you pay attention to the things that social-media executives do and don’t remove from their platforms, you’ll discover a pattern. Despite what they publicly claim, I’d argue that social-media companies don’t ban people simply for disseminating dangerous misinformation—they ban people whose misinformation makes their leadership uncomfortable at liberal dinner parties. And since most of these companies are American companies, it’s mostly just American content that proves embarrassing enough to get policed. Donald Trump lying about the election being stolen and inciting his followers to riot in the Capitol was embarrassing and somewhat frightening, and so he got removed. Anti-vaccine content is embarrassing and somewhat frightening, and so it gets labeled or removed. By contrast, government-linked Ethiopian groups inciting mass murder, human traffickers in the Middle East advertising their wares, anti-Muslim actors spurring genocide in Myanmar, or Iran’s Supreme Leader denying the Holocaust and repeatedly referring to the home of half the world’s Jews as a “cancerous tumor” to be excised—denying one genocide and advocating another—are not embarrassing. The populations these violations affect are far away, do not make much noise in San Francisco, and do not come up in everyday conversation. And so the content targeting them remains.

The sad reality is that if abuse on a social-media platform doesn’t make the company’s executives socially uncomfortable in their daily lives, it’s unlikely to get attention. And most global anti-Semitism fits that bill.

UPDATE (11/17, 8:20pm ET): Twitter has now taken down the specific tweets flagged in this post, thus proving our thesis that the company will remove such content when it becomes sufficiently embarrassing. The good news: it seems that all we need to do to solve the problem of anti-Semitism on social media is to publish a new piece each time such content appears. The bad news: I now need to hire about 1,500,000 interns. Send your applications to deepshtetl@theatlantic.com.

This isn’t a post about solutions. But I hope that by better understanding the incentives that cause social media’s problems, we can finally begin to formulate better responses to them. Those approaches may come from within the social-media industry or outside it; be legislated through the democratic process; or be enacted via the collective action of everyday users. I certainly don’t have all the answers, so I’m eager to hear your own ideas. As always, feel free to send them my way at deepshtetl@theatlantic.com.

OK, this is not what I meant by “solutions”

Thank you for reading this edition of Deep Shtetl, a subscriber newsletter for The Atlantic. You can sign up for the free version of the newsletter here. To receive the paid version, support this work, and gain access to the entire Atlantic site, be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.