But What About the Books?

The publishing and media industries have come to epitomize how corporate America has lost the plot.

Looking for a gift for the inquisitive people in your life? Give an Atlantic subscription this holiday season.

It being the holiday season, I have recently rewatched one of my favorite Christmas films, Elf. For those unfamiliar with the movie, the actor Will Ferrell plays a grown orphan named Buddy who, as a baby, crawled into Santa Claus’s pack on Christmas Eve and went on to be raised by elves on the North Pole. One day, after he discovers that he is not really an elf, he decides to venture from the Candy Cane Forest to find his biological father, Walter Hobbs, played by the late, great James Caan. The catch is, of course, that Buddy’s dad is not a very good person—in fact, he’s so bad he’s even on Santa’s naughty list.

How does the filmmaker envision such a despicable character? Why, as a publishing executive in New York—and not just any publishing executive, but one who doesn’t care at all about books and whose driving motivation is to deliver profits to his even harder-nosed bosses. When we meet Walter, he’s taking books back from a nun who missed payments on a large order and publishing children’s books with pages missing because “no one pays attention to them anyway.”

It was hard not to think of Walter Hobbs when, last week, Markus Dohle stepped down as the CEO of Penguin Random House after being in some version of this position since 2008. During his 14 years stewarding the conglomerate, it published award-winning works of literary significance, like Colson Whitehead’s novel The Underground Railroad, and blockbusters like Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming. Yet, when Christoph Mohn, the chairman of the supervisory board of Penguin Random House’s parent company, Bertelsmann, issued an official statement on the resignation, he had this to say: “We regret Markus Dohle's decision to leave Bertelsmann and Penguin Random House. Under his leadership, our book division more than doubled its revenues and quintupled its profit. The fact that our global book publishing group is in such a strong position today is largely thanks to Markus Dohle.”

In other words: Thanks for the profits, Markus! Wait, but what about the books? What about the impact on the culture created by titles supported under Dohle’s decade and a half of leadership? Mohn’s message seems to be, “Books, schmooks! Why talk about products and impact when you can celebrate being good at mergers and growth?”

To be fair, Bertelsmann CEO Thomas Rabe appears to acknowledge that those profits were generated by human beings typing words that were deemed culturally relevant enough to bind between covers (and, hopefully, sell). His contribution to the statement includes a commendation of Dohle’s having “signed and retained numerous authors for the publishing company.” It does not, however, address what those authors actually produced. But why should we expect Mohn or Rabe to acknowledge the role that books play in their business when Dohle himself barely did? Dohle’s mandate was not to produce quality books whose inherent value would drive consumers to purchase them, but to deliver more and more profits to shareholders. When the only clear path he could see toward that end—a merger with a fellow publishing giant, Simon & Schuster—was blocked in a recent federal antitrust ruling, it seems that Dohle was out of ideas.

I’m so fixated on these statements because if one of the world’s largest publishers, which has put an indelible mark on literature and culture at large, can talk about a massive corporate shakeup without ever acknowledging the pride in and import of the product that they produce, we, my friends, have lost the plot.

To me, the Bertelsmann announcement shone a light on a problem plaguing not just publishing but American culture in a time of hyper-capitalism, writ large. Words like “pride in product” or “excellence” or “quality” are far less frequently touted than phrases like “cost-cutting” and “franchise” and “margins.” Gone are the Lee Iacoccas of the corporate world, who inspired employees and consumers alike with pride in the quality of their goods (in Iacocca’s case, American cars). Now we have slash-and-burn CEOs like Warner Bros. Discovery’s David Zaslav, whose “vision” for his company involved tanking CNN+ and shelving HBO Max’s Batgirl. The rhetoric of corporate leaders today makes it clear that all executives are now in the exact same business: the profit-delivery business.

The how, why, or what of these companies’ existence seems a second (or possibly tertiary) concern to whether profits are growing and shareholders are happy. More amazing to me is that even the pretense of caring—about the products, or about having motivated employees who feel like stakeholders in a shared mission—has also gone out the window.

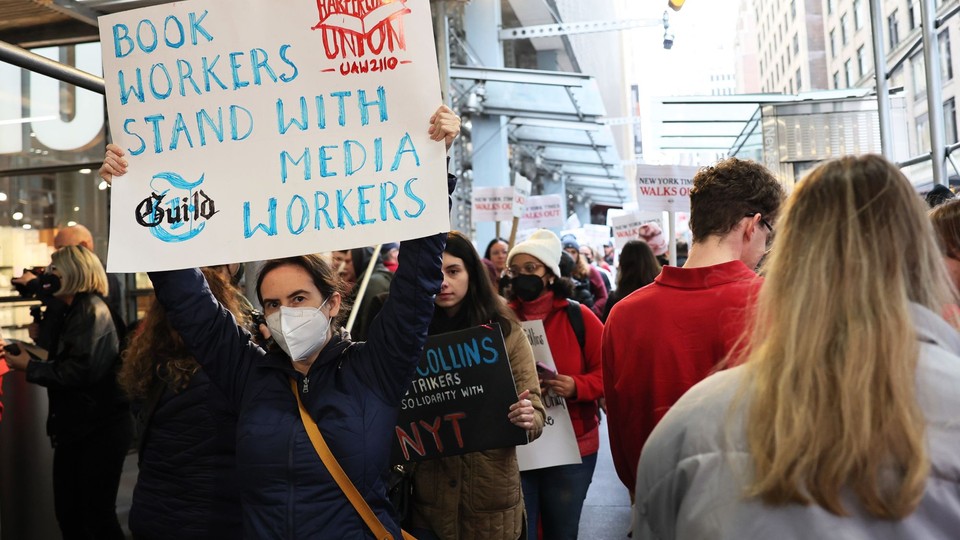

Is it any wonder, then, that the media and publishing labor force is not just disgruntled, but downright furious? From the current strike at HarperCollins (now more than a month long) to last week’s newsroom walkout at The New York Times to the lawsuits against Twitter 2.0 and the looming strike of my own union, the Writers Guild of America, the employees working to generate those rosy corporate earnings are pissed. While some are motivated primarily by a desire—in the example of the HarperCollins strike—to earn a living wage, the workers’ dissatisfaction is coupled with their simmering sense of frustration with corporate leadership that doesn’t value their contributions to the company’s purpose. And this is where things get tricky.

If, for example, you are a young publishing professional, you presumably chose to work in the field because you wanted to be in the business of books. To help bring quality books to market. To cultivate writers and talent. To shape culture. If the industry perceives the function of the business as revolving around doing those things in order to earn profit, then, of course, the young staffers should be valued for their contributions. But, as evidenced by the Penguin Random House statement, books are just a byproduct of the company’s real mission: expanding corporate profits. And corporate profits are delivered not just by producing great books (or TV shows or movies or newspapers or cable shows) but by mergers, controlling costs, depressing wages, and cutting fat when and however the company can.

The issue, as far as I can tell, is that while everyone acknowledges that money is good and necessary in a capitalistic society (if any of these publishing workers didn’t, they wouldn’t be asking for more of it), very few among us said, when asked what we wanted to be when we grew up, “I really want to work in profits!” No one says—nor wants to say—when asked what they do for a living: “I deliver corporate earnings!” Even as that is increasingly what corporate leadership seems to distill labor, particularly in creative industries, into.

Is it any wonder that the workers in these companies don’t care about shutting down a newsroom or a publishing house—or potentially an entire entertainment industry—when the suits in “corporate” have made it clear that they not only don’t care about the employees, but sound increasingly indifferent to the very products that drew these employees to these fields in the first place?