The Workout That Actually Makes Me Happy

My workouts have always been defined more by fear and duty than by joy. Grow With Jo changed that.

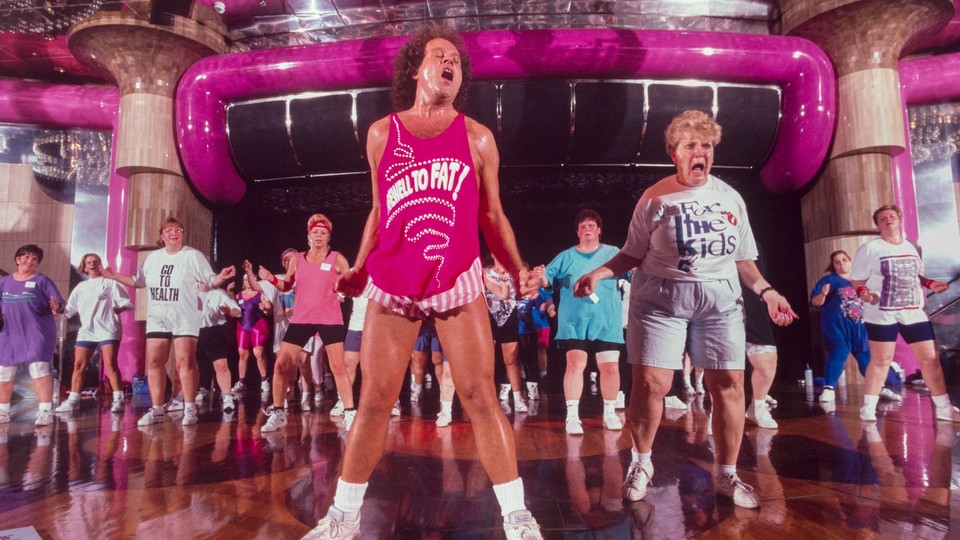

Something you should know about me: I’m kind of an exercise addict, and I have been since the mid-’90s. It started when I gained some version of the Freshman 15, and, having never been to a gym before but certainly having danced, I ordered Richard Simmons’s Sweatin’ to the Oldies. The choreography wasn’t particularly difficult, but it was also not boring; the music was great; and, well, who is more encouraging for a soul than Richard Simmons? So successful were my results (a little too successful, but that’s for another newsletter) that soon other girls in my dorm were joining me as we grapevined off the pounds to the sounds of “Gimme Some Lovin’.” After my Richard Simmons era, there was step aerobics, then spin classes at Crunch, pilates with Mari Winsor, Zumba, pilates in a studio, a brief dalliance with pole dancing, yoga, Tracy Anderson Method DVDs, running, Bikram yoga, SoulCycle, Bar Method, SoulCycle again, and then the pandemic, when I reunited with Tracy Anderson via her online studio. (I have never been in better shape than when I was doing Tracy Anderson workouts.)

My exercise addiction is complicated and, with brief exceptions such as my time with Richard Simmons, it has been defined more by fear and duty than by joy. You have to understand, I was hardwired before body positivity was a thing. It’s difficult to describe the amount of affirmation that I received when I lost that weight my freshman year. Soon enough, working out evolved into something I did out of fear that I would return to that fleshier version of myself.

I’d never set out to have a Kate Moss body, but society—especially in that era—certainly told me that I should. And the message I got from the instructors at the front of the room—either being yelled at me over a microphone or cooed during their motivational chats—was that I could. If, of course, I committed to working hard. Never mind the fact that I, and many women, are fundamentally shaped differently than the Kate Moss body type. A lack of the desired result (often defined as looking, if not like a model, then at least like the instructor) was almost always attributed to a lack of commitment. This created a new phase: exercise as an exercise in failure. Being too afraid of flab to not show up, but knowing there was no number of classes you could ever take to “succeed.”

I’m not unaware of the racial and ethnic undercurrents in my personal journey with working out. It’s not lost on me that I’d never given a thought to my weight before my immersion in the predominantly white and wealthy culture of my college. It’s also not lost on me that I spent the majority of my time in group-fitness classes surrounded by white, affluent women. I was in my mid-20s, licking my wounds from the worst of my eating disorder, when I read a New York Times article discussing a newfound sense of body positivity among teens and attributing it, in part, to the mainstreaming of Black and Latino culture. I distinctly remember feeling both othered and annoyed. I’d been born too soon to be peer-pressured by my own cultural norms.

Eventually, at some point in my 30s, I came to realize that exercise also felt good. Working out might not have been my favorite part of the day, but I loved how I felt afterward. It helped me calm and manage my overactive mind. When I exercise regularly, I am happier and less prone to runaway thoughts. I am able to manage stress and anxiety with far greater ease, so much so that, even on the busiest days of my book tour, I would rise at five to get in a quick workout. It wasn’t just something for me—it was to the benefit of all those around me. Exercise wasn’t necessarily fun, but it was a personal duty, if you will.

One morning in February, after a months-long battle with sciatica that my acupuncturist and I thought we had won, I woke up and realized I had lost the war. I couldn’t stand or sit or lie down without excruciating, tear-inducing pain. My workout routine had been in fits and starts all winter, which had been grossly affecting my mood, and now I found myself wearing a back brace and shuttling to a chiropractor three times a week. I was losing my mind.

In April I was cleared to start rehab with a personal trainer, and by May I was given the okay to resume my Tracy Anderson mat workouts. (I know, there’s no fitness instructor who embodies white affluence more, but I love that she doesn’t talk, it feels great, and—I know I’m not “supposed to care,” but I’ve already admitted that I do—it yields great results.) A month ago I was cleared to resume cardio, with restrictions: 15–20 minutes max to start, as low-impact as I can get. Clueless as to what I could possibly do, my mind went back to the beginning: I asked Dr. Google for a 15-minute dance workout. Intrigued by the premise of a 2000s dance party, I clicked and found myself immersed in the world of Johanna Devries, also known as Grow With Jo.

In my living room, all by myself, I had a fucking ball. It was the music. It was the moves: not overly complex, but fun to do. It was Jo! All smiles and with the demeanor a girlfriend you’d hit up a club with. No screaming at you, no ceaseless motivations or affirmations, no choreography so complicated you felt you might actually be auditioning for something when class was over. Just a really happy-looking woman, dancing in her living room while you danced in yours.

I think that’s why she has become a YouTube sensation with more than 2.4 million subscribers. Most of Jo’s workouts are walking-based, nearly all of them filmed in her living room, some as her little dog looks on from his nearby dog bed. Her primary moment of engagement with the viewer is a greeting and summary at the start of each workout—one that she films after she herself has done it, her friendly face glistening with a little sweat. She tells you the goals of the workout and reminds you to freestyle if a move is too hard for you and to just keep moving. Then it’s music and steps and kicks and some good sweat. Jo doesn’t try to be a guru or a shaman or an authority; she comes across more as a workout buddy or accountability partner.

Which is not to say that she lacks an aspirational quality. Jo looks beautiful. She is a young Black woman with a totally healthy body, who, as you can see from videos on her website, walked herself back into shape after having a baby. She has a fabulous figure, not in the way of a woman who’s starved herself for three weeks to fit into a dress for a party, but in the way of a mom who commits to making time for herself to work out because it feels great. And that is what she is selling at the start of her videos (all of which are free, by the way): helping you feel great through movement, through sleeping more, and through nutrition.

More than anything else, what is aspirational about Jo is how much she seems to be enjoying herself and how contagious that feeling can be. I wouldn’t be writing about this if it weren’t true: Jo has made me excited to work out for the first time in years. Not for the results, not for the endorphins afterward, but for the sheer act of moving around, the gratitude for being able to do so, and the fun of doing it.