The Courage Factor

Having guts isn’t in the job description for many of America’s most important roles, but maybe it should be.

It took me a long time to arrive at this, but I now think of myself primarily as an artist. My medium is words, and my task is to evoke: feelings, thoughts, buried memories, complicated emotions, what have you. No matter the medium, artists’ shared occupational requirements are to produce work and to be evocative. If we’re really doing our job, what we produce will be provocative as well, sparking conversation or debate or even anger.

Like many occupations, though, being an artist—particularly a working one—comes with some extraneous duties and necessary skill sets. Time management, verbal communication skills, responsiveness, and reliability are all things that would be listed as “major pluses” if there were a job description for all artists. But one unspoken qualification likely separates the good from the great: a courageous spirit.

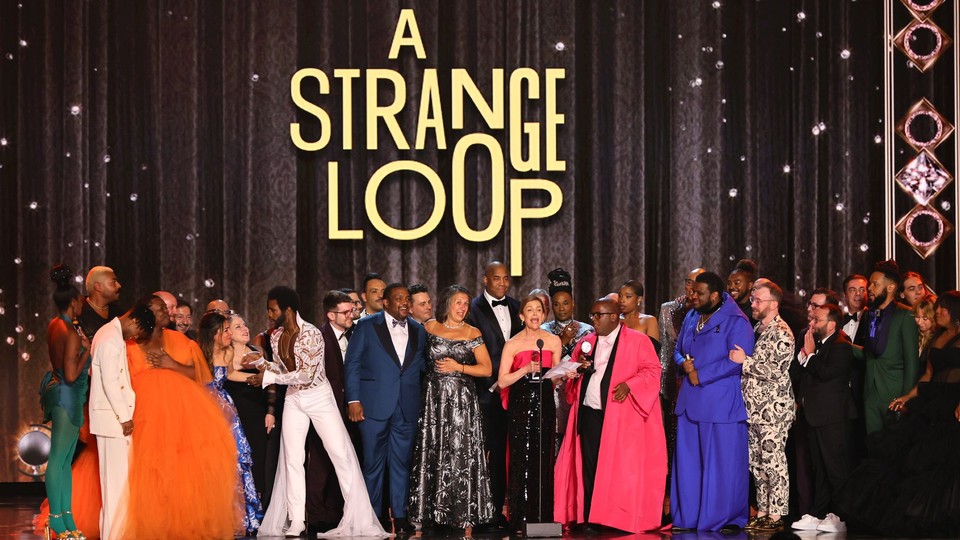

I thought about this last week when I saw the now Pulitzer Prize–winning and Tony Award–winning musical A Strange Loop. The show takes great risks as it eschews the white gaze, challenges the very conceit of plot, and tackles the internalized effects of racism and homophobia on a queer Black man. Its subject matter is handled in such utterly original ways, and the risks pay off. But the most courageous act of its playwright, the brilliant Michael R. Jackson, is to sacrifice a powerful cultural sacred cow, Tyler Perry.

A Strange Loop is a play about a playwright writing a play called A Strange Loop, so I feel okay talking about it here, as there aren’t real “spoilers” in the show (but you should go and see it immediately!). Suffice to say, if the show has a villain, it is Perry. Though the media mogul is not a physical character in the show, he is present as a cultural icon nearly from the start, and he and his work are eventually slayed, skewered, and roasted. As one review noted, “Tyler Perry won’t be optioning this musical” anytime soon. Indeed, the send-up is so brutal that it has prompted the creation of a Twitter account that simply tracks if he has seen the show yet.

Artistically, taking on the kind of shows, plays, and films that Perry produces and the ways in which they reinforce homophobia in the Black community felt necessary. But for Jackson, as a young creator trying to get this show on Broadway—to say nothing of the rest of his career—making a public enemy out of one of the richest, most powerful men in Hollywood, who also owns a massive production studio … well, that takes guts. Guts, and passion, and understanding that this choice is the right choice—for the project, for the art, and for Jackson as an artist.

Great art should speak truth to power. But that requires courage and conviction, especially as a nonwhite creator, to fight for your risky choices, because you know that’s the only way to expand the aperture of our cultural lens. For Jackson, after a very long journey, it paid off. For many others, it doesn’t. And I lament the wonderful artistic product that never sees the light of day because a gatekeeper might not have the same courage as an artist.

Art is not the only profession where courage is required to really do the job well—be it explicitly laid out in the job description or not. Yet it’s not always present in the people chosen for the task. For instance, as we wonder if Congress’s January 6 hearings will amount to anything or if this tepid gun-control compromise will hold, it’s hard to believe that there was once a book written about elected leaders called Profiles in Courage. This might sound like a simple knock on Republicans, but as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pointed out after the Uvalde school shooting, the lack of will to change things (or the lack of courage) is a problem on both sides of the aisle. Congress needs to be inhabited not by people who want to hold on to their jobs, but by those who aren’t afraid to lose them. We always ask our candidates what they will do once they get elected, but we rarely question what they will do that might piss people off and possibly not get them reelected.

I’ve been keeping this same idea in mind while following the efforts to recall San Francisco’s attorney general, Chesa Boudin, who was ousted from office on June 7. Boudin had been elected on a platform of criminal-justice reform and police reform. He immediately committed to not prosecuting certain low-lying offenses and to ending cash bail. He did this because he believed it was the right and necessary thing to truly change a system, and he did it in spite of pushback from the police. His bold moves in office were a risk that pissed a lot of people off, and ultimately, be it due to politics, reality, or both, voters did not feel that the risk was worth it. Not everyone can win a Tony—or survive a recall—but at least Boudin went in and tried.

Courage isn’t an explicit requirement for artists, politicians, civil servants, CEOs, or any other number of professions that affect our lives, our society, and our environment, but maybe it should be.