Fight Gentrification: Read a Book on the Subway

A defunct newsstand, a pop-up bookstore, and models for revitalizing NYC communities.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been talking nonstop. When I’m not waxing poetic in this newsletter, I’ve been deep in the promotion cycle for my forthcoming novel, Olga Dies Dreaming, which publishes on January 4. Because the book deals, in part, with a family in the cross-hairs of gentrification in Brooklyn, gentrification has, naturally, been a topic in many of the interviews I’ve done. One of the most provocative questions on the matter came from Maris Kreizman of The Maris Review.

“What,” she asked, “can a person who transplants here [to New York] do to not be a part of the problem of gentrification?” I’m not an urban planner, so I’m not sure I’m fully qualified to answer that question. But what came to me then—and after reflection, I stand by it—was this: Are you becoming a part of the community in which you live? Have you taken the time to know the person who does your wash-and-fold, or sells you your coffee, or tends the bodega you run into for eggs?

Often, the answer is no—which doesn’t mean the transplant is personally flawed. Joining a community relies on something that, as a society, we’ve gotten very bad at: talking to other human beings. Going out to bars to meet people has been replaced by swiping on an app, truncated texts are substitutions for phone calls to friends, and now, even the very concept of work meetings has been turned into a 2-D, digital experience. All of which has meant less time looking and talking to each other and more time, head down, enraptured with our screens.

We are, simply put, out of practice.

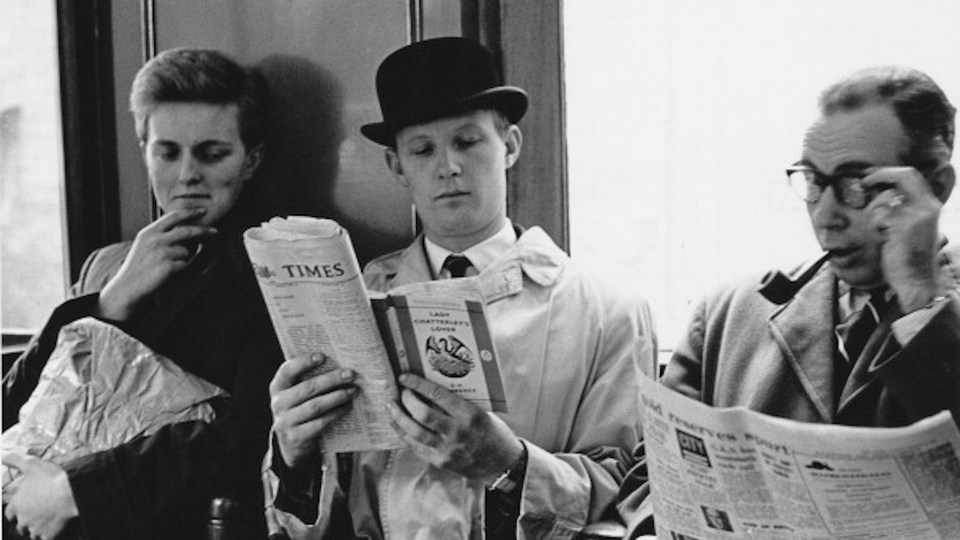

Admittedly, even before the invasion of the phone screen, New Yorkers—even the most die-hard among us—were rarely Chatty Cathies. Living, eating, and commuting in such close proximity to one another requires some kind of sensory armor. Music, sudoku puzzles, the newspaper, and, of course, books have long been ubiquitous in the common spaces of our urban landscape. And there is no space more common than the subway.

One New York transplant who quickly assessed the state of the train car saw, hidden in the quest for public solitude, an opportunity to build community. Uli Beutter Cohen is an artist and “professional conversationalist” hailing from Germany who moved to New York seven years ago after a stint in Portland. One day, in 2013, while waiting for the subway, she noticed how many people were still reading real, physical books while they commuted. E-readers had already proliferated, but between spotty cell service and the inconsistent reliability of our subway system, the good ol’ physical book remained, and still does, a trusted companion for many straphangers. Uli decided to approach one of her fellow commuters and ask her about what she was reading. She then took that person’s photo and documented the exchange on a decidedly digital platform: Instagram. Subway Book Review was born.

It was an immediate hit that has grown, over the past seven years, into more than just an account with a following, but a bona fide community, as well as a brilliant book, recently published, called Between the Lines. And how could it not have? First, if there’s anything New Yorkers are happy to do, it’s give an opinion—about anything, but particularly about the subway … and books. We are, after all, a literary city. Second, in a place with the largest income gap in America, Sunday Book Review has been a testament to the diverse population that shares one of the few democratic spaces left in New York. Yes, there’s a swath of this city that can avoid the subway altogether (though they likely spend much of their time in traffic), but the majority of us are subject to the universally crappy nature of the transit system. The home health-care attendant standing elbow to elbow with the banker or advertising executive, many of them sharing in the common experience of waiting and reading. And sometimes reading the same books while waiting for the very same trains.

That Subway Book Review captures such a diversity of people is a testament to Bueller Cohen’s devotion to capturing the true breadth of New York. She sometimes rides entire subway lines end to end, to engage with the riders across their runs. It was this same spirit that led to her most recent endeavor: reclaiming a vacant newsstand in the Union Square Station and converting it into a pop-up bookshop intended, in part, to drive donations of books to prisoners at Rikers Island, who created a wish list of 350 titles. Because Subway Book Review is about ALL of New York—even the parts, like our prisons, that we conveniently tend to forget about.

I had the chance to pop over to the pop up this weekend because (full disclosure) I’d met Uli in passing many New York moons ago, and we’d stayed in touch on social media. In advance of my book launch, she invited me to be interviewed for Subway Book Review. It was a remarkable sight, because I remembered when that space was still a newsstand, and I would buy Vibe or Vogue or Bazzini nuts there while bumping up against other New Yorkers seeking their own diversions (and snacks). I found myself growing emotional at the way in which this dialogue between the real world and the digital world had brought back to life this literal hole in the wall. And how this hole in the wall had drawn in a broad cross section of New Yorkers from all subway lines.

There are a handful of New York community makers who, like Uli, have tapped into this magic: how we can somehow take the digital that has flattened our lives and use it to enhance our three-dimensional communities and make them more vibrant. Community watchers and activists like New York Nico and Djali Brown-Cepeda at Nueva Yorkinos have begun to do more than simply document New York, and actually bring New Yorkers together to protect and celebrate one another. Some of them, like Djali, are natives—born into the fiber of this place—while others, like Uli, have personally resolved the brilliant question that Maris had asked me.

Naturally I took the train to my interview. Because I mainly write at home, and commuting has been largely curtailed from my life, it had been a while since I’d gotten to partake in the magical experience of reading on the subway. I’d forgotten how meditative it can be, and how intimately we connect with those books that are worth it to us to schlep, as opposed to the ones we lazily leave on our nightstands. (When writing my own novel and going through the arduous process of editing it, my parameter for whether to cut pages or paragraphs or chapters was whether the content made the weight of the book worth lugging around.) But I’d also forgotten how social the experience of subway reading is. How many times I’d been stopped or stopped someone else who was reading a book I’d been curious about or had just finished, to see what they thought.

In addition to buying some books while I was there, I snapped up one of Subway Book Review’s signature totes, emblazoned with the words “Ask me what I’m reading.” On my way home, music blasting in my headphones, someone tapped me on the shoulder. “So, what are you reading?” And I delighted in our conversation for the next two stops, a giant smile on my face.