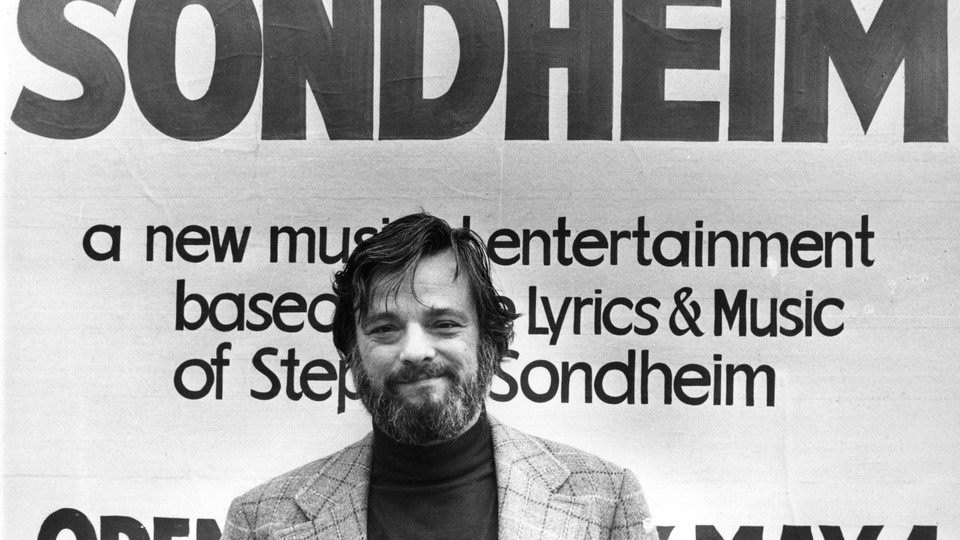

Stephen Sondheim, Way Off Broadway

“The history of the world, my sweet, is who gets eaten and who gets to eat” landed differently at Edward R. Murrow High in the ’90s.

When I am sad—motherless-child, no-one-in-the-world-understands-me kind of sad—I go on YouTube and watch performances of Stephen Sondheim musicals. Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury in Sweeney Todd, Elaine Stritch belting out songs from Company, Joanna Gleason and Bernadette Peters in Into the Woods, Patti LuPone doing just about anything. I sing along (badly) to these brilliant songs and feel comforted knowing that within an hour or two, there will be virtually no note on the scale of human emotions that would not have been touched upon. It is impossible to feel utterly alone after spending time in Mr. Sondheim’s expansive catalog, because eventually, a song or a lyric or even just one of his marvelous harmonies wil find its counterpart in your soul and pull you—hard, unapologetically—toward it. Like seeing like, and in that recognition, offering catharsis.

Like many of my comfort rituals, this one with Sondheim—or a variation of it, anyway—was born in my youth. Not in my house or even a Broadway theater, but in the hallways of my public high school, deep in Brooklyn. There, during an otherwise cash-strapped era for extracurriculars around the city, some dedicated teachers and a fiscally ingenious principal managed to sustain a theater program. (How? Hint: vending machines that sold not-quite-junk- food. Chocolate Cow soda, peanut butter crackers with “cheese.” This low-brow food paid for our access to high-brow culture.)

The Edward R. Murrow Players’ Circle mounted four shows a year: two main-stage musicals in our dilapidated auditorium and two “straight plays,” which would be staged in our black-box theater, a.k.a., a classroom painted black. In a school crowded with, literally, at least a thousand too many students and lacking any competitive sports teams, theater was our football. Curtain-up on opening night was as big a deal as kickoff in the first game of the season in Texas. And our ambitions were just as grand: During my tenure there, we mounted productions of A Raisin in the Sun, The Diary of Anne Frank, a suite of Molière plays, and no less than three Sondheim musicals.

This is likely conjuring in your head a school populated by middle-class, smiling-faced, musical-theater nerds; the dorks of the place gathered around, singing show tunes. And, in a way, this vision is absolutely true: The school’s reputation attracted a certain type of teenager, seemingly reared on original cast recordings. But the full picture of our ecosystem was far more complex and diverse. The stars of our shows were school celebrities, and there was no barrier to landing a role, other than preparing to sing a song and reading a few lines. It was the kind of set up that drew in the curious from all walks of public-school life. Here, I must confess to having been one of the curious, having wandered into an audition before landing in more than a few productions myself.

Our casts and crews included ravers, rappers, stoners, and art kids, among other misfits. In a time when city teens were living lives far older than our years, our theater program provided community, friendship, marketable skill training, a creative outlet, and in some cases, just a good reason to not have to go home after school. Or even a distraction from the fact that you might not have had a home to go to at all.

Which brings me back to Sondheim. On the surface, to a bunch of poor and working-class kids in outer Brooklyn, musical theater and all of its trappings should have been deemed “corny.” It was, after all, the milieu of ’90s grunge- and rap-music scenes—genres defined and judged at the time by raw honesty and authenticity. Not exactly qualities one associates with big chorus numbers. But the genius and joy of Sondheim was that even when working in the most fantastical settings—that of a 19th-century pointillist painter or ancient Rome—he never shied from using the genre to speak to the darkest realities of the human experience. He was, in short, a wordsmith and quick-witted truth teller. Absolutely fit to stand toe to toe with a Kurt Cobain or a Nas.

When, in my freshman year, we mounted a production of Into the Woods, I remember it bringing the house down. On Broadway, at $250 a seat, the premise of the show itself—that there’s no real such thing as “happy ever after”—is a charmingly droll conceit. But to a bunch of jaded city kids sitting in our overheated auditorium, it was a recognition of a worldview so many of us had already arrived at. A year later, when we staged Sweeney Todd (with almost an exact replica of the original Hal Prince set), it again hit home with our student body. Regardless of what we were taught in actual history class, when our Sweeney sang, “The history of the world, my sweet, is who gets eaten and who gets to eat,” the line landed among the audience at Edward R. Murrow High School in a totally different way than I would experience, years later, in the orchestra section of a production at Lincoln Center.

I am forever grateful for my introduction to Mr. Sondheim’s music, particularly when I think how easily I could have missed it. I could have gone to a different school, one where it wasn’t thought appropriate to have teenagers in a musical about revenge killings and cannibalism. Or, more likely, one that didn’t put on musicals at all. I could have, like many New Yorkers, not have had the resources or the occasion to have seen one of his shows on Broadway. But, luckily for me, his music was delivered to my doorstep and, as music from the formative years of our lives tends to do, it bored its way into my heart. Planted roots deep and strong.

We take ownership of those songs and the artists who created them, our coming-of-age music. And I am so proud to feel that Sondheim—genius of the stage, recipient of too many honors of high culture to even enumerate—belonged to me and my friends as much as he did to the theater buffs with front-row seats on the opening nights of each and every one of his musicals. When I heard of Sondheim’s passing, I knew that, for me, and so many other alumni of my high school, the loss was deeply personal. He was the maker of music that helped so many of us make sense of the world and our place in it. And isn’t that, after all, the highest purpose of art?